Understanding Cardiovascular Health

Cardiovascular health refers to the optimal functioning of the heart and blood vessels, crucial for maintaining overall well-being. It is influenced by factors such as lifestyle, genetics, and environmental exposures (5). Research highlights that systemic approaches, including reducing salt intake, can significantly lower risks of hypertension and related disorders (6). Furthermore, the integration of gender-specific insights has enhanced understanding of conditions like ischemic heart disease, leading to tailored therapeutic strategies (7). Advances in pharmacogenomics are offering new frontiers in personalized medicine, targeting genetic variations that affect cardiovascular drug efficacy (8). Additionally, system dynamics modeling of the human circulatory system has provided innovative solutions for predicting and managing cardiovascular conditions (9). A deeper understanding of drug-induced adverse reactions is pivotal for improving patient outcomes in hypertension treatment (10). These multidisciplinary perspectives highlight the complexity and opportunities in understanding cardiovascular health.

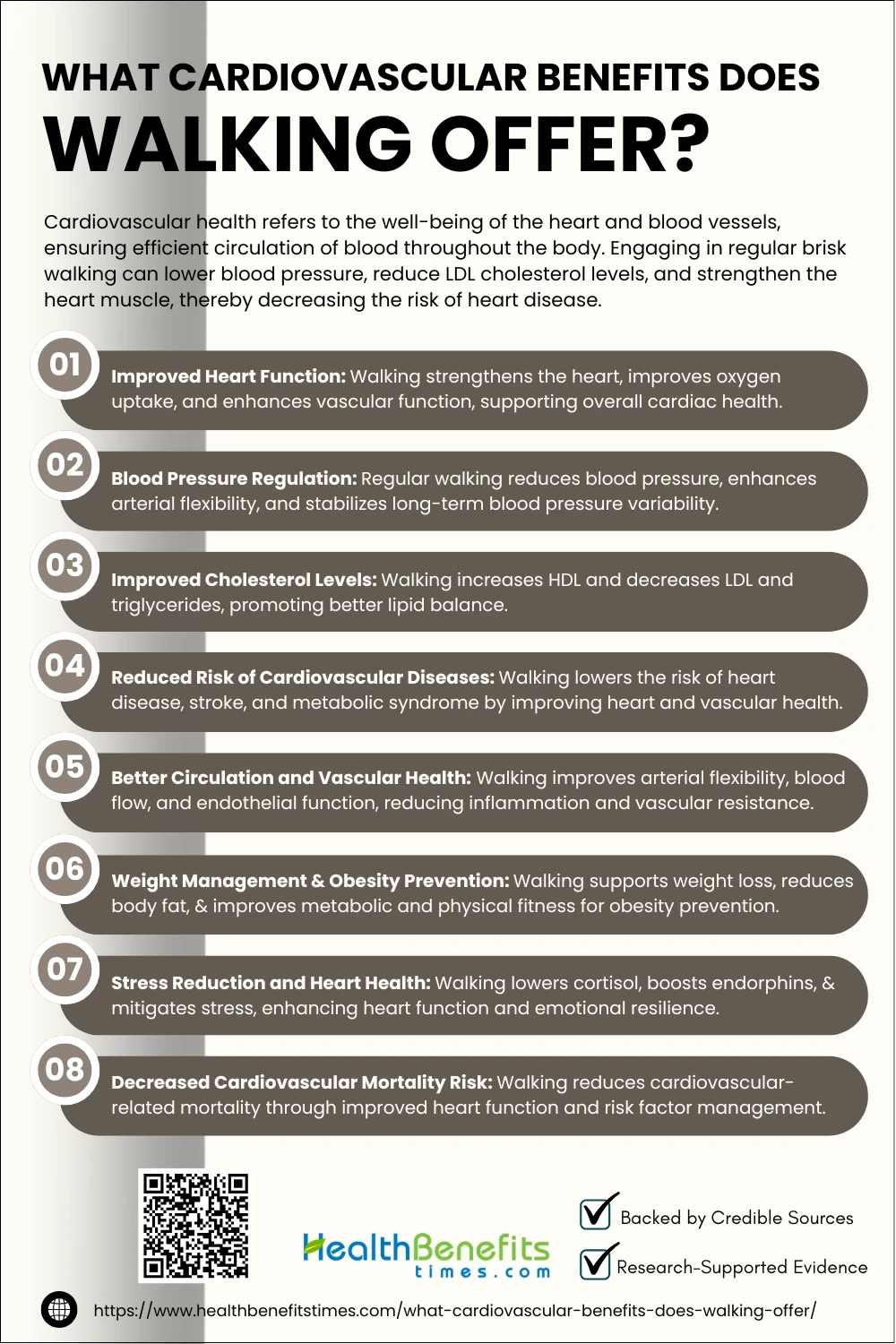

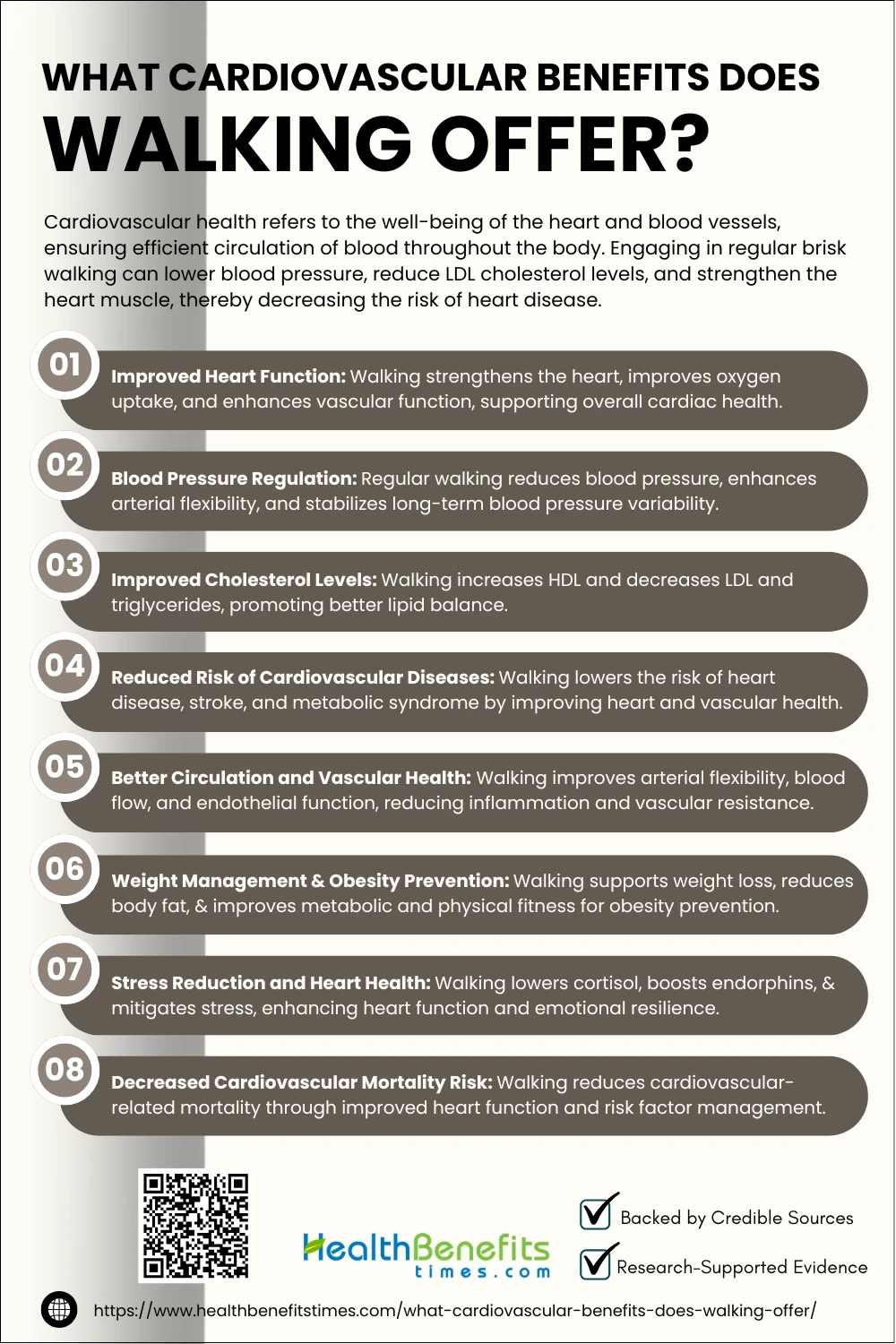

What cardiovascular benefits does walking offer?

Walking is a simple, accessible exercise with profound cardiovascular benefits. It strengthens the heart, lowers blood pressure, improves cholesterol levels, and reduces the risk of heart disease and stroke. Regular walking supports weight management, enhances circulation, and alleviates stress, making it a powerful, low-impact way to boost heart health and overall well-being.

Regular walking enhances cardiovascular health by strengthening heart muscles, improving oxygen uptake, and maintaining a steady heart rate. It reduces resting heart rate, making the heart more efficient at pumping blood (11). Walking also increases vascular endothelial function, which prevents arterial stiffness and supports circulation (12). Evidence suggests that walking improves cardiac function in patients with chronic conditions, such as heart failure and hypertension (13). It offers significant benefits for metabolic health, reducing strain on the cardiovascular system (14). Moreover, studies show it enhances inspiratory muscle strength, further supporting heart efficiency (15). Walking has even been linked to novel therapeutic benefits through cellular-level improvements (16).

2. Blood Pressure Regulation

Walking plays a vital role in regulating blood pressure by improving arterial flexibility and reducing vascular resistance (17). Regular walking enhances coronary blood flow and reduces hypertension risks, even in individuals with peripheral arterial disease (18). Studies highlight walking’s ability to stabilize hemostasis under hypoxic conditions (19). Additionally, it reduces visit-to-visit blood pressure variability, promoting long-term cardiovascular health (20). Walking also enhances circulation, lowering cholesterol and blood pressure (21). Cerebral blood flow regulation further underscores its therapeutic effects (22).(23)

3. Improved Cholesterol Levels

Walking significantly improves cholesterol levels by increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL) while reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) (24). Brisk walking has been shown to effectively reduce total cholesterol and triglycerides (25). Home-based walking programs significantly lower cholesterol in cardiac patients (26). Pedometer-based walking interventions promote sustainable improvements in lipid profiles (27). Nordic walking enhances metabolic health and lipid balance (28). Wearable activity tracker-guided walking programs also demonstrate efficacy in improving cholesterol (29).

4. Reduced risk of Cardiovascular diseases

Walking substantially lowers the risk of cardiovascular diseases by improving heart function, enhancing vascular health, and reducing blood pressure and cholesterol levels (30). Regular walking mitigates the risk of secondary cardiovascular events, such as strokes and myocardial infarctions (31). Brisk walking significantly reduces the onset of metabolic syndrome, a precursor to heart disease (32). Studies show enhanced cardiovascular endurance and reduced weight gain in consistent walkers (33). Elderly individuals also benefit from improved functional cardiac capacity (34).

5. Better Circulation and Vascular Health

Walking improves vascular health by enhancing arterial flexibility, promoting better blood flow, and reducing vascular resistance (18). Regular walking reduces chronic stress and improves endothelial function, which is crucial for vascular integrity (35). Studies reveal walking enhances oxygenation and vascular adaptations in muscles (36). Prehabilitation programs incorporating walking improve circulatory health in cardiac patients (37). Furthermore, walking mitigates inflammation, a major contributor to vascular disorders (38).

6. Weight Management and Obesity Prevention

Walking effectively aids weight management and obesity prevention by increasing calorie expenditure and promoting metabolic health (39). Studies show that walking for 150 minutes weekly leads to significant weight reduction and prevents obesity-related conditions (40). Incorporating walking into daily routines can reduce body fat percentage and improve insulin sensitivity (41). Patients report improved physical fitness and emotional well-being, fostering sustainable weight management (42). Gastroenterologists recommend walking as a primary obesity prevention strategy (43).

7. Stress Reduction and Heart Health

Walking significantly reduces stress by lowering cortisol levels and improving mood through the release of endorphins, enhancing heart health (44). Regular walking reduces blood pressure and enhances emotional stability, reducing the risks associated with hypertension (17). Studies highlight walking’s role in mitigating chronic stress, which positively impacts cardiovascular function (45). Walking improves sleep quality and overall resilience, key factors for stress management (35). Implementing home-based walking exercises enhances functional heart capacity (46).

8. Decreased Cardiovascular Mortality Risk

Walking significantly reduces cardiovascular mortality risk by enhancing cardiac function and lowering blood pressure, as shown in clinical studies (47). Regular walking decreases the incidence of cardiovascular-related deaths in patients with heart failure (48). Structured walking programs also mitigate risk factors such as elevated cholesterol and stress (49). Population studies demonstrate reduced hospitalizations and mortality rates with increased walking routines (50).

Recommended Walking Practices for Cardiovascular Benefits

Starting with moderate-intensity walking is recommended for cardiovascular therapy as it enhances aerobic capacity and reduces hypertension (51). A gradual increase in pace improves vascular health without overburdening the heart (52). Regular sessions of 30 minutes optimize heart rate and oxygen uptake (53). Structured programs combining walking with nutritional advice further improve cardiovascular outcomes (54).

2. Incorporate Pedometer-Based Tracking

Incorporating pedometer-based tracking into walking routines enhances motivation and adherence, improving cardiovascular outcomes (55). Pedometers help patients monitor physical activity levels, aligning with recommended guidelines for cardiovascular health (56). Self-monitoring encourages consistent walking habits, reducing cardiovascular risks (57). Meta-analyses show that pedometer interventions significantly boost daily activity in cardiac rehabilitation patients (58). Combining pedometers with structured exercise programs achieves optimal benefits (59).

3. Increase Walking Distance Gradually

Gradually increasing walking distance enhances cardiovascular endurance and minimizes injury risks (60). Start with short walks and progressively extend duration to improve vascular function (61). This method adapts the heart to increased workloads while boosting oxygen utilization (54). Consistent incremental goals help maintain motivation and compliance (41).

4. Pair Walking with Dietary Changes

Combining walking with dietary modifications significantly enhances cardiovascular health. Walking promotes weight control and complements heart-healthy diets like the Mediterranean diet (62). Studies show that low-fat diets paired with regular walking reduce cholesterol and improve metabolic health (63). Cardiovascular rehabilitation emphasizes this holistic approach (64). Incorporating dietary strategies improves adherence to physical activity regimens (65).

5. Adopt Supervised Walking Programs

Supervised walking programs provide structured, medically-guided routines tailored to individual needs, enhancing cardiovascular outcomes (66). Supervised regimens reduce cardiovascular risks by incorporating evidence-based contraindications (67). They foster confidence and sustained participation, crucial for long-term benefits (68). Multidisciplinary approaches further optimize outcomes (69).

6. Monitor Heart Rate during Walking

Monitoring heart rate during walking optimizes cardiovascular benefits by maintaining intensity within the target aerobic zone (70). Heart rate monitoring ensures safety and efficiency in achieving fitness goals (71). Wearable devices provide real-time feedback, improving compliance (72). Studies recommend regular adjustments to ensure progressive overload and adaptation (73).

7. Personalize Walking Routines

Personalizing walking routines ensures cardiovascular therapy aligns with individual health needs and capabilities (41). Tailored programs improve adherence and maximize benefits, particularly in managing chronic conditions (60). Context-specific interventions, such as rural health adaptations, demonstrate feasibility and effectiveness (74). Personalized approaches incorporate aerobic exercises, optimizing functional capacity (75). Monitoring and adjusting routines based on progress ensures sustained cardiovascular improvements (76).

8. Walk for at Least 150 Minutes Weekly

Walking for at least 150 minutes per week is a cornerstone of cardiovascular therapy, reducing risks for heart disease and enhancing physical fitness (77). Studies affirm that moderate-intensity walking boosts cardiorespiratory health (78). This routine improves heart efficiency while managing hypertension and obesity (79). Additionally, it aligns with American Heart Association guidelines for cardiovascular benefits (80).

How much do I need to walk?

Walking at least 150 minutes per week, spread across 5 days, is recommended for cardiovascular health improvement (81). Studies suggest brisk walking lowers blood pressure and cholesterol (82). Individuals aiming for weight management may require additional weekly walking duration (83). Monitoring progress ensures optimal benefits (84). Adopting incremental goals prevents injuries (85).

Conclusion

Walking is a simple yet powerful exercise with remarkable cardiovascular benefits, making it an essential part of a healthy lifestyle. Regular walking improves heart function, lowers blood pressure, enhances circulation, and reduces the risk of heart disease and stroke. It also helps regulate cholesterol levels, manage weight, alleviate stress, and promote overall well-being. Accessible to individuals of all ages and fitness levels, walking is a sustainable and low-impact activity that significantly decreases cardiovascular mortality risk. By incorporating walking into daily routines and following recommended practices, individuals can take proactive steps toward achieving optimal cardiovascular health and longevity.

References:

- Craig, M., & Makepeace, R. (2024). Higher intensity exercise after encoding is more conducive to episodic memory retention than lower intensity exercise. PLOS ONE.

- Shen, Y., & Hu, G. (2024). Digital technology in the management and prevention of diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology.

- Tanaka, H. (2024). Peak cardiorespiratory fitness and destiffening of arteries. American Journal of Hypertension.

- Makepeace, R., & Craig, M. (2024). Walking and cognitive benefits: A field study. PLOS ONE.

- Welle, G. A., Miller, J. R., & Al-Abcha, A. (2024). Virtual Reality Simulation With Integrated Passive Haptics Prototype for Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory Training. Elsevier.

- Ercoşkun, H., & Nişancı, F. B. (2024). Strategies for Reducing Salt in Meat Products. Alfa Mühendislik ve Uygulamalı Bilimler Dergisi.

- Bondar, L. I., et al. (2024). Gender-Specific Insights into Depression in Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease. MDPI.

- Cacabelos, R. (2024). Progress in Pharmaceutical Sciences and Future Challenges. MDPI.

- Iapascura, V. (2024). Modeling the Human Circulatory System Using System Dynamics. UTM Repository.

- Ayuba, A. S., & Shehu, A. (2024). Assessment of Adverse Drug Reactions Among Hypertensive Patients. ResearchGate.

- Fei, J., et al. (2024). Enhancing Heart Rate-Based Estimation of Energy Expenditure and Exercise Intensity in Patients Post Stroke. MDPI.

- Miura, S. (2024). Evidence for exercise therapies for hypertensive patients. Nature.

- Yang, P. C., et al. (2024). Effects of Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback. ResearchSquare.

- Akbulut, F. P., et al. (2024). Mobile health-enhanced assessment of 6-minute walk test. Springer.

- Patsaki, I., et al. (2024). Benefits from Inspiratory Muscle Training in Cardiac Surgery Patients. ResearchGate.

- Li, P. (2024). Comparative breakthroughs in heart failure treatment. World Journal of Cardiology.

- Naibaho, R. M., & Lingga, R. T. (2024). The Effect of Progressive Muscle Relaxation on Blood Pressure Reduction. Contagion Journal.

- Zhong, L., et al. (2024). Dietary Nitrate and Blood Pressure Regulation. Frontiers in Nutrition.

- Alekseeva, O. V., et al. (2024). Physical Activity and Hemostasis Under Hypoxia. Kazan Medical Journal.

- Ernst, M., et al. (2024). Blood Pressure Variability and Physical Performance. AHA Journals.

- Zimmer, S. (2024). Benefits of Walking on Cardiovascular Health. Signos.

- Tipparti, A. (2024). Cerebral Vasoregulation and Walking. ScholarWorks.

- Balpande, M., & Siddiqui, S. (2024). Effect of Walking Exercise on Blood Pressure. Neliti.

- Sokolova, J., & Požarskis, A. (2024). Metabolic Syndrome and Outdoor Activities. ResearchGate.

- Şener, Y. Z., & Ceasovschih, A. (2024). Outcomes After Endovascular Revascularization. SAGE Journals.

- Wei-ning, Z., & Yun-yun, Z. (2024). Home Cardiac Rehabilitation. ZHONGHUA YANGSHENG BAOJIAN.

- Ibeneme, S. C., et al. (2024). Walking Programs for Lipid Control. SpringerLink.

- Della Guardia, L. (2024). Nordic Walking and Metabolic Health. Deposito Legale.

- Rezvani, F., et al. (2024). Wearable Trackers in Cholesterol Regulation. D-NB.

- Miura, S. (2024). Evidence for Exercise Therapies in Cardiovascular Health. Nature.

- Feka, K., et al. (2024). Cardiovascular Rehabilitation and Event Prevention. PMC.

- Park, D. Y., & Lee, O. (2024). Walking and Metabolic Syndrome Prevention. Elsevier.

- Laksana, A. A. N. P., et al. (2024). Locomotor-Based Learning Models in Cardiovascular Health. Jurnal Speed.

- Samoilova, I. G., et al. (2024). Cardiovascular System Function in Elderly Walkers. Vrach.

- Saretzki, G. (2024). Stress and Endothelial Function. Frontiers in Endocrinology.

- Yáñez-Sepúlveda, R., et al. (2024). Vascular Adaptations in Rehabilitation. Frontiers in Physiology.

- Twiddy, M., et al. (2024). Cardiac Prehabilitation. medRxiv.

- Benucci, S. (2024). Walking and Inflammatory Pathways. Unibas eDoc.

- Adamović, A., et al. (2024). Modern Approaches in Obesity Treatment. Scindeks.

- Swanson, A., & Watrin, K. (2024). Effective Weight Loss with Walking. Journal of Family Practice.

- Janež, A., et al. (2024). Aerobic Exercise and Obesity Prevention. Frontiers in Clinical Diabetes and Healthcare.

- Dogan, U. (2024). Precision Stimulation and Weight Control. ResearchGate.

- BHL III. (2024). Weight Loss Strategies for Obesity. MDedge.

- Bhunia, S., et al. (2025). Stress Management and Cardiovascular Benefits. ClinicSearch.

- Sulistiadi, W., et al. (2024). Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Health. Springer.

- Ramamoorthy, L. (2024). Walking Interventions for Heart Health. LWW Journals.

- Xu, H., et al. (2024). Mid-term outcomes of walking for cardiovascular health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

- Vinogradova, N. G., et al. (2024). Results of walking in heart failure management. PubMed.

- Belenkov, Y. N., et al. (2024). Walking and structured outpatient care. PubMed.

- Rose, D. K., et al. (2024). Walking programs and hospitalization reduction. JMIR Research Protocols.

- Albarzinji, N., & Jalal, A. (2024). Multicentric osteolysis and moderate exercise. PMC.

- Paoletti, F. (2024). Cardiovascular benefits of moderate walking. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

- Chu, A. T., & Mehta, A. (2024). Moderate walking intensity and heart health. Journal of Sexual Medicine.

- Aivazova, E. S., et al. (2024). Walking and structured cardiovascular therapy. ru.

- Fedorchenko, Y., & Zimba, O. (2024). Enhancing chronic disease management through pedometry. Rheumatology International.

- Phongsavan, P., et al. (2009). Physical activity dose-response effects in cardiac rehab. Journal of Cardiac Rehabilitation.

- Kaminsky, L. A., et al. (2013). Pedometer use in cardiac rehabilitation. Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy.

- Hodkinson, A., et al. (2019). Meta-analysis on pedometer-based interventions. JAMA Network Open.

- Vasavi, V. L., et al. (2022). Pedometer-based exercise in cardiac rehabilitation. F1000Research.

- Mukhanova, A. A., & Rymkhanova, A. R. (2024). Gradual activity increases in cardiovascular therapy. Elibrary.

- Hilton, D. (2024). Active transport for cardiovascular health. Injury Prevention.

- Smith, T. C., et al. (2007). Walking and dietary changes in diabetes management. Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

- Wadden, T. A., et al. (2012). Lifestyle modification for obesity. Circulation.

- Moffat, M. (2007). Cardiovascular rehabilitation strategies. Books Google.

- Lakka, T. A., & Laaksonen, D. E. (2007). Lifestyle changes and metabolic syndrome. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism.

- Reljic, D., et al. (2024). Supervised walking programs and clinical outcomes. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.

- Trevizan, P. F., et al. (2023). Risk mitigation in walking regimens. PubMed.

- Kempf, K., & Martin, S. (2022). Benefits of supervised exercise therapy. BMJ Open.

- Moholdt, T., et al. (2023). Multidisciplinary walking interventions. ResearchGate.

- Bashir, N. (2024). Importance of heart rate in cardiovascular therapy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

- Reljic, D., et al. (2024). Benefits of heart rate monitoring. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.

- Rezvani, F., et al. (2024). Wearable heart rate monitors in therapy. Deutsches Bibliothek.

- Lieb, S., & Thaler, M. R. (2024). Heart rate-based walking programs. SpringerLink.

- Sekome, K. (2024). Feasibility of rural-specific interventions. Loughborough Repository.

- Caruso, M. (2024). Rehabilitation management in cardiovascular care. University of Padua Thesis.

- Myers, M. (2024). Pro-bono wellness personalization for cardiovascular health. Academy Scipro.

- Manson, J. A. E., Greenland, P., & LaCroix, A. Z. (2002). Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events. New England Journal of Medicine.

- Anton, S. D., Duncan, G. E., & Limacher, M. C. (2011). How much walking improves cardiorespiratory fitness? Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.

- Gordon, B. A., Bird, S. R., & Price, K. J. (2016). Cardiac rehabilitation exercise programs. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology.

- Leon, A. S., Casal, D., & Jacobs, D. (1996). Effects of 2,000 kcal/week of walking on coronary heart disease risk. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation.

- Solomon, K., Diaz, V., & O’Connor, J. (2024). Preoperative cognitive testing insights. FIU Digital Commons.

- Birabwa, C., et al. (2024). Self-reported care-seeking pathways. Global Health Science & Practice Journal.

- Bauer, E., Razfar, A., & Skerrett, A. (2024). Critical religious literacy. SAGE Journals.

- Lindström, J. (2024). Community and prisoner interactions. Septentrio Nordic Journal.

- Grave, R. D., Sartirana, M., & Calugi, S. (2024). Cognitive behavior therapy. Springer.

Comments

comments