- A diet rich in unprocessed grains like brown rice, oats, and whole wheat, retaining their bran, germ, and endosperm.

- Whole grains are packed with fiber, magnesium, and potassium, which help relax blood vessels and regulate blood pressure levels.

- Studies show that regularly consuming whole grains can lower hypertension risks, improve cholesterol levels, and support overall heart health.

Whole-grain diets consist of unrefined grains that retain their bran, germ, and endosperm, offering essential nutrients such as fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Common examples include oats, brown rice, whole wheat, quinoa, and barley (1). The link between whole-grain consumption and blood pressure management has been extensively studied, revealing multiple pathways through which these grains exert their benefits. Whole grains are rich in dietary fiber, particularly beta-glucan, which has been shown to reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure (2). Additionally, their high potassium and magnesium content contributes to vascular relaxation and improved arterial function (3). Studies indicate that individuals who consume whole grains regularly have a significantly lower risk of hypertension (4). These findings are further supported by meta-analyses showing a consistent blood pressure-lowering effect across diverse populations (5). The anti-inflammatory properties of whole grains also play a critical role in reducing vascular inflammation, a key contributor to hypertension (6). Moreover, regular intake of whole grains is associated with better insulin sensitivity, which indirectly supports blood pressure regulation (7). Despite their clear benefits, whole grains remain underutilized in many diets, emphasizing the need for public health strategies to encourage their consumption (8). Understanding these mechanisms offers compelling evidence for promoting whole grains as an essential dietary component for cardiovascular health (9).

Whole-grain diets consist of unrefined grains that retain their bran, germ, and endosperm, offering essential nutrients such as fiber, vitamins, and minerals. Common examples include oats, brown rice, whole wheat, quinoa, and barley (1). The link between whole-grain consumption and blood pressure management has been extensively studied, revealing multiple pathways through which these grains exert their benefits. Whole grains are rich in dietary fiber, particularly beta-glucan, which has been shown to reduce systolic and diastolic blood pressure (2). Additionally, their high potassium and magnesium content contributes to vascular relaxation and improved arterial function (3). Studies indicate that individuals who consume whole grains regularly have a significantly lower risk of hypertension (4). These findings are further supported by meta-analyses showing a consistent blood pressure-lowering effect across diverse populations (5). The anti-inflammatory properties of whole grains also play a critical role in reducing vascular inflammation, a key contributor to hypertension (6). Moreover, regular intake of whole grains is associated with better insulin sensitivity, which indirectly supports blood pressure regulation (7). Despite their clear benefits, whole grains remain underutilized in many diets, emphasizing the need for public health strategies to encourage their consumption (8). Understanding these mechanisms offers compelling evidence for promoting whole grains as an essential dietary component for cardiovascular health (9).

Examples of Whole-Grain Diets

Whole-grain diets emphasize the consumption of grains that retain all three parts of the grain kernel: the bran, germ, and endosperm. These diets are rich in fiber, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, offering numerous health benefits, including blood pressure regulation.

- Mediterranean Diet

- Incorporates whole grains such as whole wheat bread, bulgur, farro, and brown rice.

- DASH Diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension)

- Recommends at least 3 servings of whole grains per day.

- Nordic Diet

- Features rye bread, barley, and oats as staple whole grains.

- Whole30 Diet (Modified for Whole Grains)

- While traditional Whole30 eliminates grains, a modified version allows brown rice, quinoa, and millet for sustained energy and health benefits.

- Vegetarian or Plant-Based Diets

- Heavily rely on whole grains like brown rice, quinoa, amaranth, and whole-wheat couscous.

- Flexitarian Diet

- Encourages whole grains like whole-wheat tortillas, sorghum, and spelt.

- Gluten-Free Whole-Grain Diet

- Includes gluten-free whole grains like brown rice, quinoa, millet, amaranth, and buckwheat.

- Traditional Asian Diet

- Features grains like brown rice, black rice, and whole-grain noodles.

- High-Fiber Diets

- Incorporates grains such as steel-cut oats, barley, and whole-grain cereals.

- Balanced American Diet (MyPlate Model)

- Recommends that half of all grain intake should come from whole grains.

What is Blood pressure?

Blood pressure is the force exerted by circulating blood on the walls of the arteries, and maintaining it within an optimal range is crucial for overall health. Blood pressure is typically expressed through two values: systolic pressure, which measures the force when the heart pumps blood, and diastolic pressure, which represents the pressure between heartbeats. Elevated blood pressure, or hypertension, is a leading modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (10). Studies show a direct correlation between high blood pressure and an increased risk of heart attacks, strokes, and kidney failure (11). Even moderately elevated blood pressure levels can cause long-term damage to blood vessels and vital organs, highlighting the importance of routine monitoring and early intervention (12).

The causes of high blood pressure are multifaceted, involving genetic predisposition, lifestyle choices, and environmental factors. A sedentary lifestyle, excessive salt intake, alcohol consumption, obesity, and stress are primary contributors to hypertension (13). Additionally, underlying medical conditions such as kidney disease, diabetes, and hormonal disorders can exacerbate blood pressure irregularities (14). Prolonged hypertension increases the risk of severe health complications, including stroke, coronary artery disease, and heart failure (14). Furthermore, environmental toxins such as lead exposure have also been linked to elevated blood pressure levels (14). Addressing these risk factors through lifestyle modifications, regular health screenings, and medical interventions is vital in preventing hypertension-related complications.

How do whole-grain diets help manage blood pressure?

Whole grains have been widely studied for their role in managing and lowering blood pressure. Below are the key mechanisms and benefits supported by scientific research.

1. Rich in Dietary Fiber

1. Rich in Dietary Fiber

Whole-grain diets, rich in dietary fiber, have been shown to effectively manage blood pressure by improving vascular function, reducing arterial stiffness, and enhancing overall cardiovascular health. Studies suggest that whole grains lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure through their high fiber content, which modulates glucose and lipid metabolism (15; 16). Whole grains also promote gut microbiome health, which indirectly supports blood pressure regulation (17; 18). Additionally, increased whole-grain intake correlates with reduced inflammation and oxidative stress, further contributing to blood pressure control (19).

2. High in Essential Minerals (Potassium and Magnesium)

Whole-grain diets, rich in essential minerals like potassium and magnesium, play a crucial role in managing blood pressure. Potassium supports vasodilation, reducing arterial tension, while magnesium improves vascular function and insulin sensitivity, both contributing to lower blood pressure levels (4; 20). Whole grains also provide bioavailable forms of these minerals, essential for electrolyte balance (21; 9). Regular consumption of potassium- and magnesium-rich whole grains correlates with a reduced risk of hypertension (3).

3. Anti-Inflammatory Effects

Whole-grain diets exert anti-inflammatory effects that contribute to managing blood pressure by reducing systemic inflammation and oxidative stress. The high fiber, polyphenols, and antioxidants in whole grains decrease pro-inflammatory cytokines and improve endothelial function (22). Whole grains also improve gut microbiota composition, further reducing inflammation markers (23; 24). These effects collectively contribute to better vascular health and lower blood pressure levels (25).

4. Improved Insulin Sensitivity

Whole-grain diets enhance insulin sensitivity, contributing to improved blood pressure regulation by stabilizing blood glucose levels and reducing insulin resistance. Whole grains are rich in dietary fiber, magnesium, and antioxidants, which collectively reduce postprandial glucose spikes and improve metabolic pathways (26; 27). Increased insulin sensitivity helps regulate vascular tone and reduce arterial stiffness (2; 28). These effects make whole grains a valuable dietary tool in blood pressure management (29).

5. Reduced Sodium Absorption

Whole-grain diets can help manage blood pressure by reducing sodium absorption. The fiber in whole grains slows digestion and reduces sodium uptake in the gut, ultimately lowering blood pressure levels (20; 3). Additionally, bioactive compounds in whole grains improve renal sodium excretion (30). These effects are supported by studies showing enhanced vascular health and lower hypertension risks (31; 32).

6. Weight Management Benefits

Whole-grain diets support weight management, a key factor in blood pressure regulation, by promoting satiety, reducing overall calorie intake, and improving metabolic efficiency. The high fiber content slows digestion, reducing hunger and calorie consumption (32; 33). Whole grains also enhance insulin sensitivity, supporting better fat metabolism (34; 35). Regular consumption helps reduce abdominal fat, further contributing to blood pressure control (36).

7. Balanced Blood Sugar Levels

Whole-grain diets help balance blood sugar levels, which indirectly supports healthy blood pressure regulation. The high fiber content slows glucose absorption, preventing spikes in blood sugar and insulin resistance (16; 37). Improved glycemic control reduces oxidative stress and inflammation, key contributors to hypertension (38). These effects collectively lower the risk of developing high blood pressure (18).

8. Reduced Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases

Whole-grain diets significantly reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases by improving blood pressure regulation, reducing arterial stiffness, and lowering cholesterol levels. The high fiber content and bioactive compounds in whole grains contribute to vascular health and reduce inflammation (16; 6). Whole grains also improve lipid profiles and insulin sensitivity, further reducing cardiovascular risks (18; 5). These effects make whole grains a cornerstone in heart disease prevention strategies (39).

9. Improved Endothelial Function

Whole-grain diets improve endothelial function, contributing to better blood pressure regulation by enhancing vascular relaxation, reducing arterial stiffness, and lowering oxidative stress. The bioactive compounds, polyphenols, and antioxidants in whole grains play a vital role in maintaining endothelial health (4; 40). Regular consumption reduces inflammation and improves nitric oxide availability, which supports vascular tone (5; 1). These mechanisms collectively promote optimal blood pressure levels (41).

10. Lower Arterial Stiffness

Whole-grain diets help reduce arterial stiffness, a significant factor in managing blood pressure, by improving vascular elasticity and reducing endothelial dysfunction. The fiber, antioxidants, and polyphenols in whole grains contribute to better arterial compliance and reduced oxidative stress (42; 43). Whole grains also support nitric oxide production, which promotes vasodilation (44; 45). These benefits collectively lower the risk of hypertension (46).

Link between Whole-Grain Diets and Blood Pressure Management

Whole-grain diets are linked to better blood pressure management through multiple mechanisms, including improved endothelial function, reduced arterial stiffness, and balanced sodium absorption. Whole grains are rich in dietary fiber, potassium, and antioxidants, which collectively lower inflammation and enhance vascular health (47; 48). Regular consumption reduces both systolic and diastolic blood pressure (49; 4). These effects significantly contribute to a lower risk of hypertension and cardiovascular diseases (50).

Comparison: Whole Grains vs. Refined Grains

Here’s a differentiation table comparing Whole Grains and Refined Grains based on key factors:

| Criteria | Whole Grains | Refined Grains |

| Definition | Contain all parts of the grain: bran, germ, and endosperm. | Have the bran and germ removed, leaving only the endosperm. |

| Nutritional Value | High in fiber, vitamins (e.g., B vitamins), minerals (e.g., iron, magnesium), and antioxidants. | Lower in fiber and nutrients due to the removal of the bran and germ. Often enriched with synthetic vitamins. |

| Glycemic Index | Lower glycemic index; slower digestion, better blood sugar control. | Higher glycemic index; faster digestion, causing rapid blood sugar spikes. |

| Fiber Content | High fiber content, supports digestion and satiety. | Low fiber content, less impact on satiety. |

| Impact on Blood Pressure | Helps manage blood pressure through better sodium regulation and improved vascular function. | Limited effect on blood pressure; may contribute to hypertension if consumed excessively. |

| Cardiovascular Benefits | Reduces risk of heart disease, lowers cholesterol levels, and improves arterial health. | Limited cardiovascular benefits; excessive intake linked to higher disease risks. |

| Weight Management | Promotes satiety, reduces overeating, supports weight management. | Less satiety, may contribute to weight gain with excessive consumption. |

| Processing Level | Minimally processed, retains natural nutrients. | Highly processed, loses essential nutrients during refining. |

| Flavor and Texture | Earthier flavor, denser texture. | Softer texture, milder flavor. |

| Common Examples | Brown rice, whole wheat bread, quinoa, oats, barley. | White rice, white bread, pastries, all-purpose flour. |

| Shelf Life | Shorter shelf life due to natural oils in the bran and germ. | Longer shelf life due to the removal of oils that cause spoilage. |

| Health Risks (Excessive Consumption) | Generally safe; excessive intake may cause bloating due to high fiber. | Increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. |

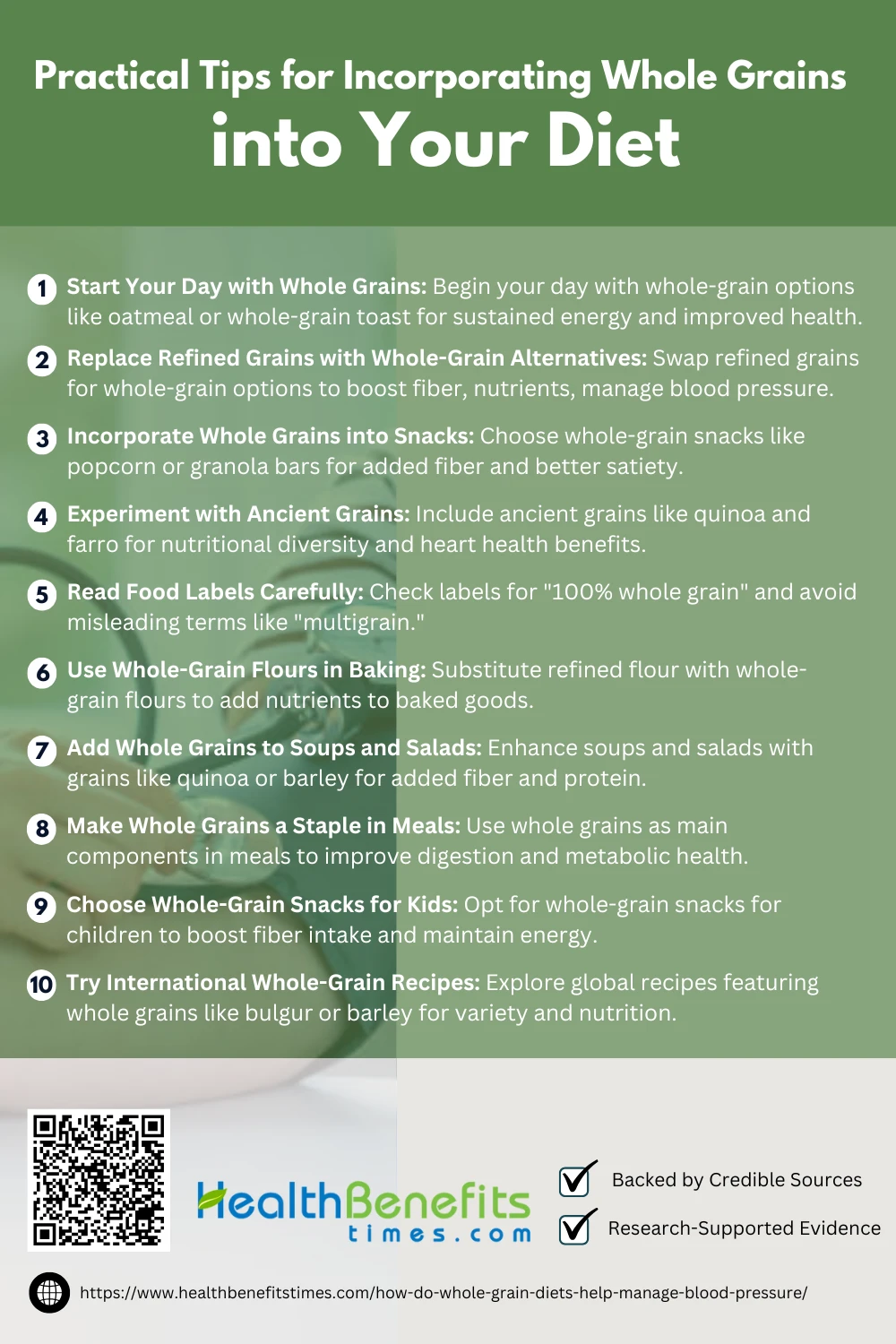

Practical Tips for Incorporating Whole Grains into Your Diet

1. Start Your Day with Whole Grains

1. Start Your Day with Whole Grains

Starting your day with whole grains is a simple and effective way to support blood pressure regulation and overall health. Breakfast options such as oatmeal, whole-grain cereals, or whole-wheat toast provide sustained energy, improve satiety, and support metabolic health (27; 51). Whole grains also contribute to better glucose control and reduce inflammation (52; 53).

2. Replace Refined Grains with Whole-Grain Alternatives

Replacing refined grains with whole-grain alternatives is a practical and effective way to improve dietary quality and manage blood pressure. Swap white rice with brown rice, white bread with whole-grain bread, and refined pasta with whole-grain versions to boost fiber, vitamins, and minerals (54; 55). Whole grains also support better insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation (56; 20).

3. Incorporate Whole Grains into Snacks

Incorporating whole grains into snacks is an easy way to boost daily fiber intake and improve overall health. Opt for popcorn, whole-grain crackers, or oat-based granola bars as healthier alternatives to refined snacks (57; 58). Whole-grain snacks support better satiety, insulin sensitivity, and nutrient intake (27; 59).

4. Experiment with Ancient Grains

Incorporating ancient grains like quinoa, farro, amaranth, and teff into your meals adds nutritional diversity and health benefits. These grains are rich in protein, fiber, and essential minerals, contributing to better blood pressure management and metabolic health (27; 60). Ancient grains also have unique bioactive compounds that promote cardiovascular health and reduce inflammation (61; 62).

5. Read Food Labels Carefully

Reading food labels carefully is essential for identifying authentic whole-grain products. Look for terms like “100% whole grain” or “whole wheat” as the first ingredient, and avoid products labeled “multigrain” without specifics (63; 64). Check fiber content and avoid excessive added sugars or artificial additives (65; 56).

6. Use Whole-Grain Flours in Baking

Using whole-grain flours in baking is an excellent way to increase fiber, vitamins, and minerals in homemade bread, muffins, and other baked goods. Substitute refined flour with whole-wheat, spelt, or oat flour for a healthier alternative (58; 54). Whole-grain flours retain essential nutrients lost during refining, improving heart health and reducing inflammation (66; 67).

7. Add Whole Grains to Soups and Salads

Adding whole grains to soups and salads is an easy and versatile way to enhance nutrition. Grains like quinoa, farro, barley, and brown rice add fiber, protein, and essential minerals while improving satiety and heart health (68).

8. Make Whole Grains a Staple in Meals

Making whole grains a staple in your meals provides sustained energy, improved digestion, and better heart health. Replace refined grains with brown rice, quinoa, barley, or bulgur as main meal components (54; 63). Whole grains are rich in fiber, essential nutrients, and bioactive compounds that reduce inflammation and improve overall metabolic health (20; 69).

9. Choose Whole-Grain Snacks for Kids

Choosing whole-grain snacks for kids is an easy way to improve their diet quality while boosting fiber intake and satiety. Options like whole-grain crackers, oat bars, or air-popped popcorn are healthier alternatives to refined snacks (68; 70). Whole grains support digestion, maintain energy levels, and contribute to overall health (71; 64).

10. Try International Whole-Grain Recipes

Exploring international whole-grain recipes can add variety and nutrition to your diet. Dishes like quinoa salads, bulgur pilafs, or barley soups provide fiber, essential minerals, and antioxidants while supporting heart health (57; 72). Global cuisines often highlight whole grains’ versatility, making them easy to integrate into daily meals (73; 74).

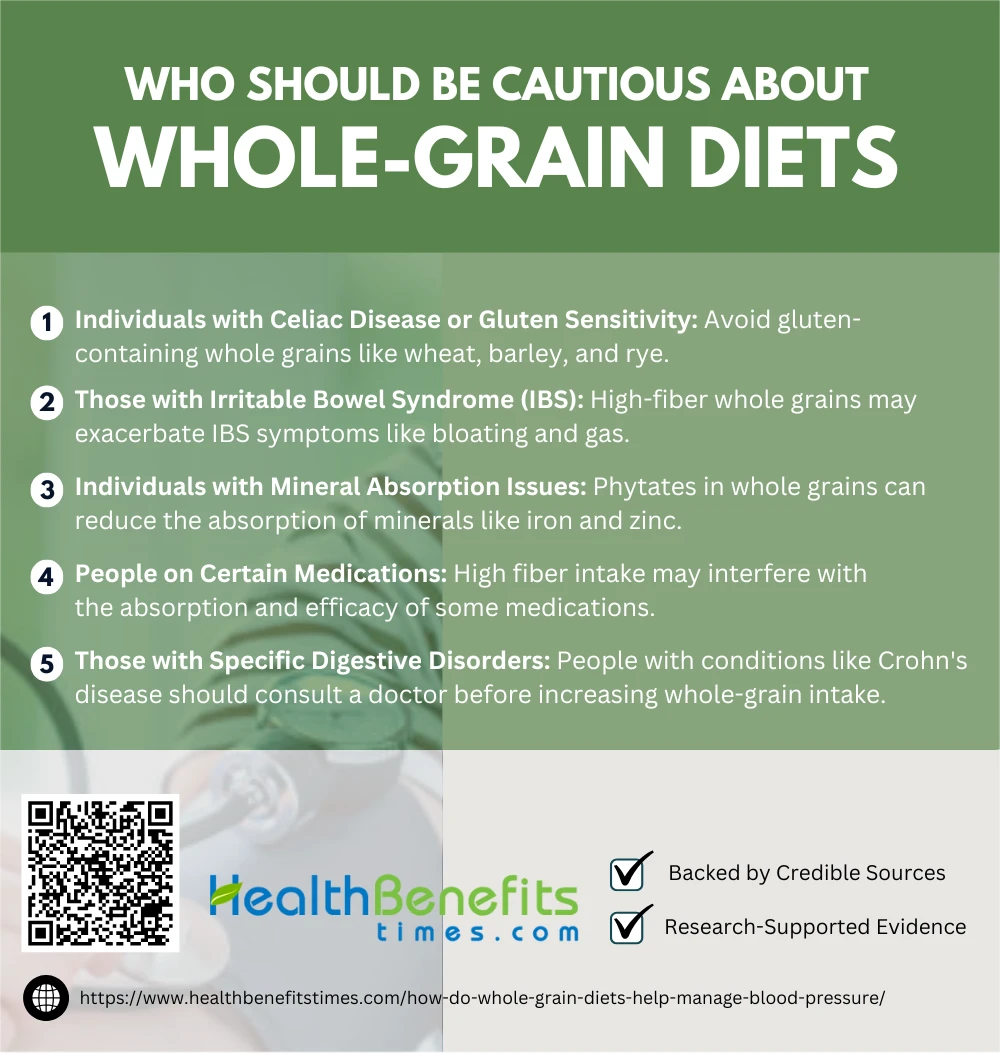

Who Should Be Cautious About Whole-Grain Diets?

- Individuals with Celiac Disease or Gluten Sensitivity:

People with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity must avoid gluten-containing grains such as wheat, barley, and rye (75). - Those with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS):

High-fiber whole grains can worsen IBS symptoms, leading to bloating, gas, or discomfort (35). - Individuals with Mineral Absorption Issues:

The phytates present in whole grains may reduce the absorption of essential minerals like iron and zinc (76). - People on Certain Medications:

High fiber intake from whole grains can interfere with the absorption of certain medications, affecting their efficacy (77). - Those with Specific Digestive Disorders:

Individuals with chronic digestive issues, such as Crohn’s disease, should consult a healthcare professional before increasing whole-grain intake (15).

Potential Challenges and Considerations

Discover the common challenges and key considerations when adopting a whole-grain diet, including digestion issues, gluten sensitivity, and balanced nutrition.

1. Digestive Discomfort

1. Digestive Discomfort

Digestive discomfort is a common concern for individuals consuming high amounts of whole grains, primarily due to their high fiber content. People with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) may experience worsened symptoms (58). Additionally, individuals with compromised gut health may struggle to break down certain fibers, exacerbating symptoms (17). Gradual introduction of whole grains, paired with adequate hydration, can help alleviate these issues (78).

2. Nutrient Absorption Issues

Nutrient absorption issues are a concern with whole-grain diets due to compounds like phytates, which can bind essential minerals such as iron, calcium, and zinc, reducing their bioavailability (58). Phytic acid, commonly found in the bran of whole grains, interferes with mineral uptake in the intestines (79). While whole grains provide important nutrients, excessive consumption may exacerbate deficiencies in vulnerable populations (80). Proper preparation techniques, such as soaking, sprouting, and fermenting grains, can help reduce phytate content and improve mineral absorption (30).

3. Cost and Accessibility

The cost and accessibility of whole grains present significant barriers to adoption, particularly in low-income populations. Whole-grain products are often priced higher than their refined counterparts, limiting access for economically disadvantaged communities (81). Limited availability in certain regions also hinders widespread adoption, particularly in food deserts where refined grains dominate (58). Consumer education and clear food labeling are critical, as many individuals struggle to identify genuine whole-grain products (82). Policy interventions, such as subsidies or incentives, could help bridge the affordability gap (30).

4. Texture and Taste Preferences

Texture and taste preferences pose significant barriers to the widespread adoption of whole-grain diets. Many people find the denser texture and earthier taste of whole grains less appealing compared to refined grains (54). These sensory differences can lead to reduced acceptance, particularly among children and individuals accustomed to refined products (83). Whole grains often have a grainier mouthfeel, which may discourage consistent consumption (84). Addressing these preferences through better processing techniques and culinary creativity can help increase acceptance (85).

5. Label Confusion

Label confusion remains a significant challenge in adopting whole-grain diets, as misleading packaging can obscure the true whole-grain content of products. Terms like “multigrain,” “wheat bread,” and “stone-ground” often mislead consumers into believing they are purchasing whole-grain products (86). Additionally, inconsistent labeling standards across regions add to consumer confusion (57). Clear and regulated labeling is necessary to guide consumers towards healthier choices (87). Enhanced educational campaigns can also help consumers better understand nutritional labels (65).

Common Myths about Whole-Grain Diets

- Myth: Whole Grains Are Always Gluten-Free

Many people mistakenly believe that all whole grains are gluten-free. While grains like quinoa and brown rice are safe, wheat, barley, and rye contain gluten and should be avoided by those with gluten intolerance. - Myth: Whole Grains Cause Weight Gain

Some believe that consuming whole grains contributes to weight gain. In reality, whole grains are rich in fiber, which helps in satiety and weight management when consumed in moderation. - Myth: Whole Grains Are Hard to Digest

While some individuals may experience digestive discomfort due to high fiber content, most people can gradually increase their whole grain intake to allow their digestive system to adapt. - Myth: Refined Grains Are Just as Nutritious

Whole grains contain more fiber, vitamins, and minerals compared to refined grains, which lose essential nutrients during processing. - Myth: All “Whole-Grain” Labels Are Accurate

Many products labeled “multigrain” or “wheat bread” may not actually be whole-grain. Consumers should check labels for terms like “100% whole grain”

Conclusion

Incorporating whole grains into your diet is a simple yet effective way to help manage blood pressure and support overall heart health. Packed with essential nutrients like fiber, magnesium, and potassium, whole grains work to relax blood vessels, reduce cholesterol levels, and improve overall cardiovascular function. Scientific studies consistently highlight their role in lowering hypertension risks when combined with a balanced lifestyle. By making mindful choices, such as swapping refined grains for whole-grain alternatives and reading food labels carefully, you can take meaningful steps toward better blood pressure control. Remember, sustainable changes and moderation are key, and consulting a healthcare professional can provide personalized guidance for optimal results.

References:

- Slavin, J. (2003). Why whole grains are protective: biological mechanisms. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society.

- Harris, K.A., & Kris-Etherton, P.M. (2010). Effects of whole grains on coronary heart disease risk. Current Atherosclerosis Reports.

- Lillioja, S., Neal, A.L., & Tapsell, L. (2013). Whole grains, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hypertension.

- Wang, L., Gaziano, J.M., Liu, S., & Manson, J.A.E. (2007). Whole- and refined-grain intakes and the risk of hypertension in women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

- Mellen, P.B., Walsh, T.F., & Herrington, D.M. (2008). Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases.

- Jacobs, D.R., & Gallaher, D.D. (2004). Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a review. Current Atherosclerosis Reports.

- Hu, Y., Willett, W.C., Manson, J.A.E., Rosner, B., & Hu, F.B. (2022). Intake of whole grain foods and risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women. BMC Medicine.

- Capurso, C. (2021). Whole-grain intake in the Mediterranean diet.

- Marshall, S., Petocz, P., Duve, E., & Abbott, K. (2020). The effect of replacing refined grains with whole grains on cardiovascular risk factors. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics.

- Whelton, P.K. (2020). High blood pressure and cardiovascular disease.

- Stamler, J. (1991). Blood pressure and high blood pressure: aspects of risk.

- Pastor-Barriuso, R., Banegas, J.R., Damin, J. (2003). Systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and pulse pressure: an evaluation of their joint effect on mortality. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Taylor, J.O., Cornoni-Huntley, J., Curb, J.D. (1991). Blood pressure and mortality risk in the elderly. American Journal of Epidemiology.

- Ikeda, A., Iso, H., Yamagishi, K., Inoue, M. (2009). Blood pressure and the risk of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality among Japanese. American Journal of Hypertension.

- Newby, P.K., et al. (2007). Intake of whole grains, refined grains, and cereal fiber measured with 7-d diet records and associations with risk factors for chronic disease. ScienceDirect.

- Cho, S.S., et al. (2013). Consumption of cereal fiber, mixtures of whole grains and bran, and whole grains and risk reduction in type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. ScienceDirect.

- Joye, I.J. (2020). Dietary fibre from whole grains and their benefits on metabolic health. MDPI.

- Harris, K.A., & Kris-Etherton, P.M. (2010). Effects of whole grains on coronary heart disease risk. Springer.

- Reynolds, A.N., et al. (2020). Dietary fibre and whole grains in diabetes management: Systematic review and meta-analyses.PLOS Medicine.

- Rebello, C.J., et al. (2014). Whole grains and pulses: A comparison of the nutritional and health benefits. ACS Publications.

- Nicklas, T.A., et al. (2010). Whole-grain consumption is associated with diet quality and nutrient intake in adults. ScienceDirect.

- Li, C., et al. (2024). Comprehensive modulatory effects of whole grain consumption on immune-mediated inflammation. ScienceDirect.

- Rahmani, S., et al. (2020). The effect of whole-grain intake on biomarkers of subclinical inflammation. ScienceDirect.

- Hoevenaars, F.P.M., et al. (2019). Whole grain wheat consumption affects postprandial inflammatory response. ScienceDirect.

- Vitaglione, P., et al. (2015). Whole-grain wheat consumption reduces inflammation in a randomized controlled trial. ScienceDirect.

- Andersson, A., et al. (2007). Whole-grain foods do not affect insulin sensitivity or markers of lipid peroxidation. ScienceDirect.

- Pereira, M.A., et al. (2002). Effect of whole grains on insulin sensitivity in overweight hyperinsulinemic adults. ScienceDirect.

- McCarty, M.F. (2005). Magnesium may mediate the favorable impact of whole grains on insulin sensitivity. ScienceDirect.

- Malin, S.K., et al. (2019). A whole‐grain diet increases glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion. NCBI.

- Jones, J.M., & Engleson, J. (2010). Whole grains: Benefits and challenges. Annual Reviews.

- Barrett, E.M., et al. (2020). Whole grain intake compared with cereal fiber intake in association to CVD risk factors.NCBI.

- Pol, K., et al. (2013). Whole grain and body weight changes in apparently healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ScienceDirect.

- Karl, J.P., & Saltzman, E. (2012). The role of whole grains in body weight regulation.ScienceDirect.

- Harland, J.I., & Garton, L.E. (2008). Whole-grain intake as a marker of healthy body weight and adiposity.Cambridge.

- McRae, M.P. (2017). Health benefits of dietary whole grains: An umbrella review.ScienceDirect.

- Thielecke, F., & Jonnalagadda, S.S. (2014). Can whole grain help in weight management? LWW.

- Slavin, J. (2004). Whole grains and human health. Cambridge.

- Malin, S.K., et al. (2019). A whole‐grain diet increases glucose‐stimulated insulin secretion. NCBI.

- Aune, D., et al. (2016). Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality. BMJ.

- Lillioja, S., et al. (2013). Whole grains, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hypertension: links to the aleurone preferred over indigestible fiber. Wiley Online Library.

- Barrett, E.M., et al. (2019).Whole grain, bran, and cereal fiber consumption and CVD: A systematic review. Cambridge.

- Jennings, A., et al. (2019). Mediterranean-style diet improves systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness in older adults. AHA Journals.

- Cicero, A.F.G., et al. (2018). Short-term hemodynamic effects of modern wheat products substitution in diet with ancient wheat products. MDPI.

- Moore, R. (2015). The relationship between a dietary pattern high in fruits, vegetables, low fat dairy, and whole grains and vascular structure and function. OhioLINK.

- Tripkovic, L., et al. (2008). Whole-grain consumption improves arterial stiffness in young adult males.Cambridge.

- Campbell, M.S., & Fleenor, B.S. (2018). Whole grain consumption is negatively correlated with obesity-associated aortic stiffness. ScienceDirect.

- Flint, A.J., et al. (2009). Whole grains and incident hypertension in men.ScienceDirect.

- Tighe, P., et al. (2010). Effect of increased consumption of whole-grain foods on blood pressure. ScienceDirect.

- Kirwan, J.P., et al. (2016). A whole-grain diet reduces cardiovascular risk factors. ScienceDirect.

- Ross, A.B., et al. (2015). Whole-grain and blood lipid changes in apparently healthy adults. ScienceDirect.

- Hartmann, M., et al. (2023). Fifty shades of grain–Increasing whole grain consumption through daily messages. ScienceDirect.

- Liu, R.H. (2007). Whole grain phytochemicals and health. ScienceDirect.

- Okarter, N., & Liu, R.H. (2010). Health benefits of whole grain phytochemicals. Taylor & Francis.

- Ferruzzi, M.G., et al. (2014). Developing a standard definition of whole-grain foods for dietary recommendations. ScienceDirect.

- McKeown, N.M., et al. (2013). Whole grains and health: From theory to practice. ScienceDirect.

- Mozaffarian, R.S., et al. (2013). Identifying whole grain foods: A comparison of different approaches for selecting more healthful whole grain products. Cambridge.

- Ross, A.B., et al. (2017). A definition for whole-grain food products—Recommendations from the Healthgrain Forum. ScienceDirect.

- Variyam, J.N., et al. (2001). Choose a variety of grains daily, especially whole grains: A challenge for consumers. ScienceDirect.

- Kuznesof, S., et al. (2012). WHOLEheart study participant acceptance of wholegrain foods. ScienceDirect.

- Venn, B.J., & Mann, J.I. (2004). Cereal grains, legumes and diabetes. Nature.

- Călinoiu, L.F., & Vodnar, D.C. (2018). Whole grains and phenolic acids: A review on bioactivity, functionality, health benefits and bioavailability. MDPI.

- Anderson, J.W., et al. (2000). Whole grain foods and heart disease risk. Taylor & Francis.

- Kranz, S., et al. (2012). Filling America’s fiber intake gap: Summary of a roundtable to probe realistic solutions with a focus on grain-based foods. ScienceDirect.

- Dean, M., et al. (2013). Whole grains and health: Attitudes to whole grains against a prevailing background of increased marketing and promotion.NCBI.

- Beck, E., et al. (2020). Whole grains and consumer understanding: Investigating consumers’ identification, knowledge, and attitudes to whole grains. MDPI.

- Gómez, M., et al. (2020).Understanding whole‐wheat flour and its effect in breads: A review.Wiley.

- Grafenauer, S., et al. (2020). Flour for home baking: A cross-sectional analysis of supermarket products emphasising the whole grain opportunity. MDPI.

- Adams, J.F., & Engstrom, A. (2000). Helping consumers achieve recommended intakes of whole grain foods.Taylor & Francis.

- Lang, R., & Jebb, S.A. (2003). Who consumes whole grains, and how much?Cambridge.

- Chan, H.W., et al. (2008). Healthy whole-grain choices for children and parents: A multi-component school-based pilot intervention.Cambridge.

- Burgess-Champoux, T., et al. (2006). Perceptions of children, parents, and teachers regarding whole-grain foods. ScienceDirect.

- Jonnalagadda, S.S., et al. (2011). Putting the whole grain puzzle together: Health benefits associated with whole grains.ScienceDirect.

- Dean, M., et al. (2013). Whole grains and health: Attitudes to whole grains against a prevailing background of increased marketing and promotion. Cambridge.

- Miller, K.B. (2020). Review of whole grain and dietary fiber recommendations and intake levels in different countries.Oxford Academic.

- Pearce, M.S., et al. (2017). Providing evidence to support the development of whole grain dietary recommendations in the United Kingdom. Cambridge.

- Kyrø, C., et al. (2012). Intake of whole grain in Scandinavia: intake, sources, and compliance with new national recommendations. Sage Journals.

- Seal, C.J. (2006). Whole grains and CVD risk.Cambridge.

- McRae, M.P. (2017). Health benefits of dietary whole grains: an umbrella review. PMC.

- Aisbitt, B., et al. (2008). Cereals–current and emerging nutritional issues. Wiley.

- Brouns, F. (2021). Phytic acid and whole grains for health controversy. MDPI.

- Mobley, A.R., et al. (2019). Factors associated with identification and consumption of whole-grain foods in a low-income population. ScienceDirect.

- Robinson, E., & Chambers, L. (2018). The challenge of increasing wholegrain intake in the UK. Wiley.

- Barrett, E.M., et al. (2020). Whole grain and high-fibre grain foods: How do knowledge, perceptions and attitudes affect food choice?ScienceDirect.

- Klerks, M., et al. (2019). Infant cereals: Current status, challenges, and future opportunities for whole grains.MDPI.

- Heiniö, R.L., et al. (2016). Sensory characteristics of wholegrain and bran-rich cereal foods–a review.Academia.

- Wilde, P.E., et al. (2019). Labels for cereals, crackers, and breads cause consumer confusion about whole grain content and healthfulness of products. AgeconSearch.

- Kissock, K.R., et al. (2022). Knowledge, messaging, and selection of whole-grain foods: Consumer and food industry perspectives. ScienceDirect.