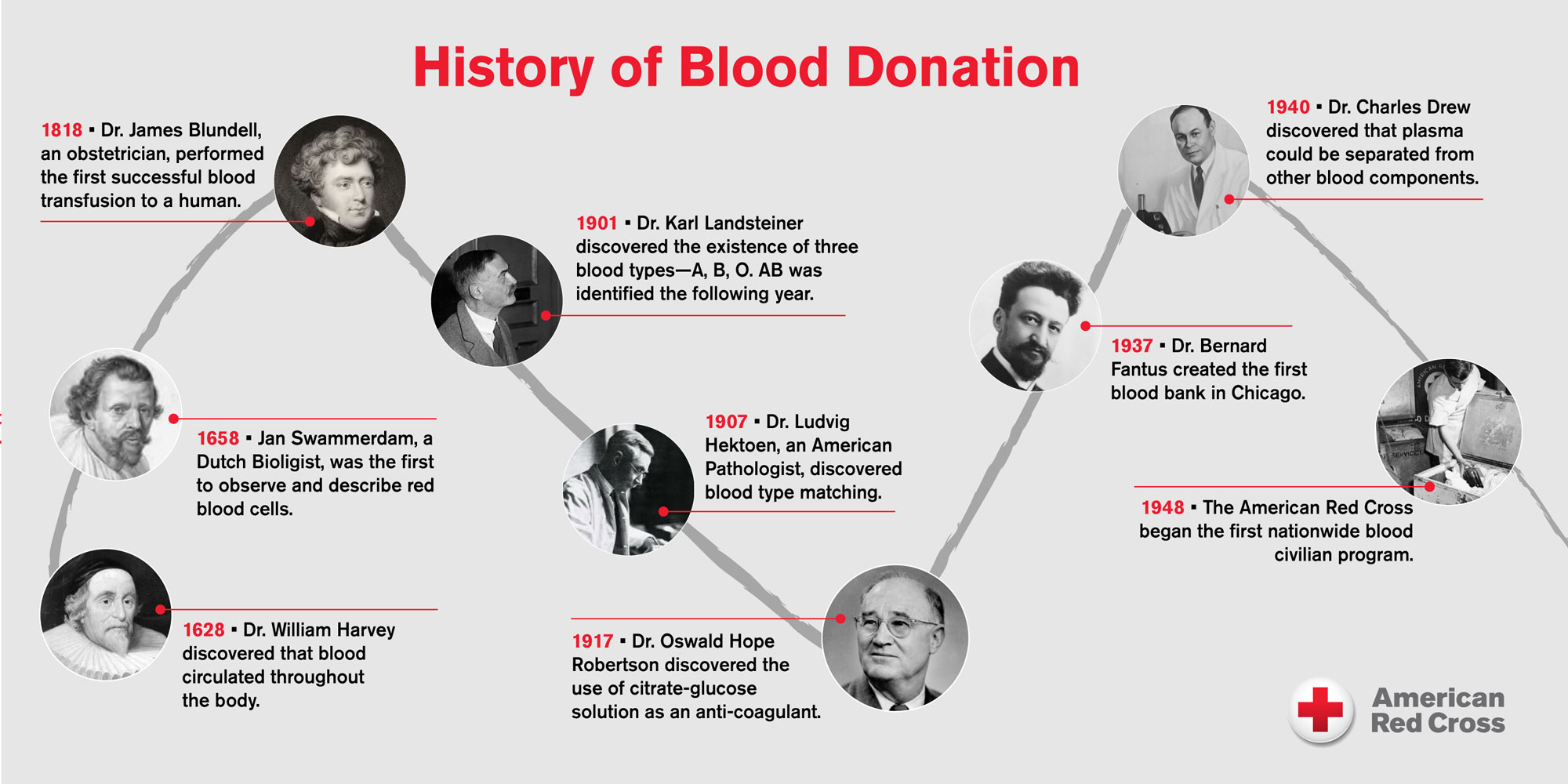

Back in 1628, British physician William Harvey discovered that blood circulates through our bodies. Know what else happened that year? The King of England told the Pilgrims they could go ahead and start a colony in Massachusetts.

Just 30 years later, using an early microscope, a Dutch biologist named Jan Swammerdam, observed and described red blood cells for the first time.

For the next 150 years, various physicians and scientists experimented with transfusion – giving dog blood to another dog, or sheep blood to humans. (Thanks, but no thanks, right?) All that experimentation eventually yielded the first successful transfusion of human blood to a human patient. British obstetrician James Blundell achieved this in 1818.

Blundell’s transfusion required blood to pass from donor to patient “directly” before it had time to clot. It took nearly 100 years before blood could be transfused “non-directly.” In 1914, it was discovered that donated blood could be stored for hours or even days if it was mixed with sodium citrate (and kept in the fridge which, fortunately, had already been invented).

If we’re able to store something as valuable as blood, obviously we need a safe place to do so. Time to invent the blood bank!

The first such facility in the U.S. was established at Cook County Hospital in Chicago back in 1937. There’s still a blood bank at Cook County Hospital to this day. The doctor who started it has other medical innovations to his credit, too – including putting candy coating on children’s medicine. Thanks, doc!

Back in the day, transfusions didn’t always have good results, and in 1907 scientists learned why – and how to improve the odds.

In 1901, Karl Landsteiner discovered the first three human blood types, which he called A, B and C (now known as blood type O). Type AB was identified the following year.

Building on that research, in 1907 Ludvig Hektoen hypothesized that the safety of transfusion might be improved by cross-matching blood between donors and patients to exclude incompatible mixtures. And he was right!

Cross matching takes time though, so in 1912 Roger Lee discovered the “universal donor” whose blood type (type O) can be given to any patient, and the “universal recipient” who can receive any type of blood (that’s a person with type AB).

So at this point in history humankind has discovered A, B, AB and O – what about positive and negative blood types? That’s known as the Rh factor, which was described in 1939-1940 by Karl Landsteiner and a few other scientists. (Yes, that’s the same man who earlier identified the main blood types. No wonder he won a Nobel Prize!)

Many of the next advances in blood donation and transfusion medicine occurred during the two World Wars.

In 1917, an American Army doctor working in a British military hospital in France (whew!) used a citrate-glucose solution that prevented blood from clotting while keeping red cells alive during storage. With this technique, Robertson was able to establish a “blood depot” and sent iced jars of preserved blood to save lives on the front lines.

Fast-forward to 1940 when the U.S. government established a national blood collection program. “Plasma for Britain” was headed by Charles R. Drew, MD., who had discovered that plasma could be separated from other blood components and frozen for long-term storage. (Even today, frozen plasma is stored for up to a year!)

Also in 1940, Edwin Cohn developed a process for breaking down plasma into components and products such as albumin, gamma globulin and fibrinogen. The very next year, soldiers injured during the Pearl Harbor attack were able to be treated with albumin for shock.

With the U.S. now involved in the war, the American Red Cross began its National Blood Donor Service to collect blood for the U.S. military at their request. Once again, Dr. Charles R. Drew led the effort. By war’s end, in 1945, the Red Cross had collected more than 13 million pints – and (spoiler alert) the know-how to create a peacetime blood program.

That’s right, the American Red Cross began the first nationwide blood civilian program in 1948.

It started in Rochester, New York. By the following year, the U.S. had a blood system comprised of 1,500 hospital blood banks, 46 community blood centers, and 31 Red Cross regional blood centers.

In the 1950s the Red Cross introduced mobile blood units (otherwise known as bloodmobiles) to enable donation and collection to take place out in local communities. Bloodmobiles, built on truck, bus and RV chassis, can still be seen at community blood drives today.

In 1972, the Red Cross called for a national blood policy, which was enacted in 1974, supporting standardized practices and an end to paid blood donations. Since 1978, the United State Food and Drug Administration has required blood bags to be labeled “paid” or “volunteer.”

Many recent advancements in blood donation and transfusion involve making the blood supply safer and transfusion medicine more effective.

Blood donations are tested for serious blood-borne illnesses before being given to patients. For example, donated blood has been tested for syphilis since 1947. Hepatitis B testing began in 1971, and hepatitis C in 2002. Blood has been tested for HIV since 1985.

In 1961, it was shown that platelets can reduce the chance of dangerous bleeding in cancer patients. Platelet collection was made easier by the 1972 introduction of apheresis, which separates blood components such as platelets before returning the rest of the blood to the donor. Apheresis machines are still used today to collect platelets, plasma and red cells.

The Red Cross started a national Rare Blood Donor Registry in the 1960s for blood types occurring less than once in 200 people. In 1998, this registry was merged with similar database developed by the American Association of Blood Banks. Today, the American Rare Donor Program coordinates access to rare blood from many thousands of donors, providing lifesaving blood that may not be available through a patient’s local blood service.

That’s a lot of facts, but the most important lesson you can learn is that blood donation is not just historic, it’s downright heroic. Because when you donate blood, you’re helping to save lives. Schedule an appointment today.

Comments

comments