Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a significant health concern that affects the colon and rectum, which are parts of the large intestine in the digestive system. It is the third most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. CRC typically develops from abnormal growths called polyps in the inner lining of the colon or rectum, which can become cancerous over time if left untreated. The disease can affect both men and women, with a slightly higher incidence in men. While CRC is most frequently diagnosed in individuals aged 65 to 74 years, there has been a concerning increase in cases among younger adults, particularly those under 50 years old. Risk factors for CRC include age, family history, inflammatory bowel diseases, and lifestyle factors such as diet, physical inactivity, and smoking. Early detection through regular screening is crucial for improving outcomes, as CRC is often treatable when caught in its early stages.

How colorectal cancer develops?

Colorectal cancer (CRC) develops through a multistep process involving a series of histological, morphological, and genetic changes that accumulate over time. This progression typically follows the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, where benign adenomas gradually transform into malignant carcinomas. Genetic alterations, such as mutations in oncogenes (e.g., KRAS) and tumor suppressor genes (e.g., APC, TP53), play a crucial role in this transformation. Additionally, epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation and microsatellite instability, contribute to tumorigenesis. Chronic inflammation, often resulting from conditions like inflammatory bowel disease, can also promote CRC development by creating an oxidative microenvironment that damages DNA. Screening and early detection of precancerous polyps are vital for reducing CRC incidence and mortality, as they allow for intervention before the polyps become cancerous. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.

Causes of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer, a prevalent malignancy affecting the colon or rectum, arises from a combination of genetic, lifestyle, and environmental factors. Understanding these causes is crucial for prevention and early detection. Below are some of the primary causes contributing to the development of colorectal cancer:

1. Age

Age is a significant risk factor for colorectal cancer (CRC). The incidence of CRC increases with age, particularly after the age of 50. This is attributed to the accumulation of genetic mutations and environmental exposures over time, which can lead to the development of cancerous cells in the colon and rectum. Studies have shown that the majority of CRC cases are diagnosed in individuals aged 50 and older, highlighting the importance of regular screening in this age group to detect and treat early-stage cancers.

2. Genetic Factors

Genetic factors play a crucial role in the development of colorectal cancer. Mutations in genes such as MLH1 and APC are known to predispose individuals to CRC. These genetic alterations can lead to the dysregulation of signaling pathways, resulting in increased cell proliferation and tumor formation. Familial syndromes like Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) and Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) are well-documented examples of inherited conditions that significantly elevate CRC risk.

3. Family History

A family history of colorectal cancer is a well-established risk factor. Individuals with first-degree relatives who have been diagnosed with CRC are at a higher risk of developing the disease themselves. This increased risk is likely due to shared genetic mutations and environmental factors within families. Genetic testing and better documentation of family medical history can help identify high-risk individuals who may benefit from earlier and more frequent screening.

4. Diet

Dietary habits significantly influence the risk of colorectal cancer. Diets high in red and processed meats, saturated fats, and low in fiber are associated with an increased risk of CRC. Conversely, diets rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains are thought to have a protective effect. The consumption of antioxidants, vitamins, and minerals found in these foods may help reduce the risk of CRC by neutralizing harmful free radicals and promoting healthy cell function.

5. Physical Inactivity

Physical inactivity is a modifiable risk factor for colorectal cancer. Sedentary lifestyles contribute to obesity and metabolic disorders, which are linked to an increased risk of CRC. Regular physical activity helps maintain a healthy weight, improves immune function, and reduces inflammation, all of which can lower the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Public health strategies promoting physical activity are essential for CRC prevention.

6. Obesity

Obesity is strongly associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. Excess body fat can lead to chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and alterations in hormone levels, all of which can promote cancer development. Studies have shown that individuals with higher body mass indices (BMIs) are at a greater risk of developing CRC compared to those with normal weight. Weight management through diet and exercise is crucial for reducing CRC risk.

7. Smoking

Smoking is a well-known risk factor for many cancers, including colorectal cancer. The carcinogens in tobacco smoke can cause genetic mutations and promote the development of cancerous cells in the colon and rectum. Long-term smokers are at a significantly higher risk of CRC compared to non-smokers. Smoking cessation programs are vital for reducing the incidence of colorectal cancer and improving overall public health.

8. Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol consumption is another modifiable risk factor for colorectal cancer. Studies have shown that heavy alcohol intake is associated with an increased risk of CRC. Alcohol can act as a carcinogen by causing DNA damage and promoting inflammation in the colon. Limiting alcohol consumption is recommended as part of a healthy lifestyle to reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.

9. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, are significant risk factors for colorectal cancer. Chronic inflammation in the colon can lead to DNA damage and increase the likelihood of cancerous cell development. Patients with IBD are advised to undergo regular screening and monitoring to detect early signs of CRC and implement preventive measures.

10. History of Polyps

A history of colorectal polyps is a known risk factor for colorectal cancer. Polyps are benign growths in the colon that can potentially transform into malignant tumors over time. Regular screening and removal of polyps during colonoscopy can significantly reduce the risk of CRC. Individuals with a history of polyps should follow recommended surveillance guidelines to prevent cancer development.

11. Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. The metabolic disturbances and insulin resistance characteristic of diabetes can promote cancer development. Diabetic patients are encouraged to manage their condition through medication, diet, and exercise to reduce their risk of CRC. Regular screening is also recommended for early detection and prevention.

Symptoms and Warning Signs of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer often presents with a variety of symptoms and warning signs that can be easily overlooked or mistaken for other conditions. Early detection is key to effective treatment, making it essential to be aware of these indicators. Common symptoms include changes in bowel habits, such as diarrhea or constipation, and unexplained weight loss. Additionally, persistent abdominal discomfort and the presence of blood in the stool are significant warning signs. Below are some of the primary symptoms and warning signs of colorectal cancer:

- Changes in bowel habits

- Blood in stool or rectal bleeding

- Abdominal discomfort

- Unexplained weight loss

- Fatigue and weakness

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea or vomiting

- Iron deficiency anemia

Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer

Diagnosing colorectal cancer involves a series of tests and procedures to detect the presence and extent of the disease. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment planning. Below are some common methods used in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer:

1. Screening Tests

Colonoscopy remains the gold standard for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening due to its ability to detect and remove adenomatous polyps, thereby preventing cancer development. The procedure involves a visual examination of the colon and rectum using a flexible tube with a camera. Despite its invasiveness and the discomfort associated with bowel preparation, colonoscopy is highly effective in reducing CRC incidence and mortality. Stool tests, such as the guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBt) and the fecal immunochemical test (FIT), are non-invasive alternatives that detect hidden blood in the stool, a potential indicator of CRC. FIT is preferred over gFOBt due to its higher sensitivity and specificity. These tests are recommended for average-risk individuals and can significantly improve early detection rates when used in population-based screening programs.

2. Imaging Tests

Imaging tests like CT scans and MRI play a crucial role in the diagnosis and staging of colorectal cancer. CT colonography, also known as virtual colonoscopy, is a less invasive alternative to traditional colonoscopy and is recommended every five years for CRC screening. It involves the use of CT imaging to create detailed pictures of the colon and rectum, allowing for the detection of polyps and tumors. MRI is particularly useful in the local staging of rectal cancer, helping to identify candidates for neoadjuvant therapy. Both imaging modalities are essential for accurate staging, which is critical for determining the appropriate treatment plan and improving patient outcomes. However, their use in routine screening is limited by cost and availability.

3. Biopsies and Lab Tests

Biopsies are the definitive method for diagnosing colorectal cancer. During a colonoscopy, suspicious polyps or tissue samples are removed and examined histologically to confirm the presence of cancer cells. Lab tests, including blood-based biomarkers, are emerging as promising tools for CRC detection. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a well-known serum biomarker used to monitor disease recurrence and treatment response, although it lacks specificity for early detection. Recent advances have identified other potential biomarkers, such as anti-p53 antibodies and DNA methylation markers, which show promise in early CRC detection and screening. These biomarkers, particularly when used in panels, can enhance diagnostic accuracy and offer non-invasive alternatives to traditional methods. However, further validation in pre-diagnostic settings is needed to establish their clinical utility.

Stages of Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer progresses through distinct stages, each indicating the extent of the disease’s spread within the body. Understanding these stages is vital for determining the appropriate treatment plan. Below are the stages of colorectal cancer:

1. Stage 0: In situ

Stage 0 colorectal cancer, also known as carcinoma in situ, is the earliest form of the disease. At this stage, abnormal cells are found in the innermost lining of the colon or rectum but have not yet spread to nearby tissues. Early detection through screening is crucial, as it significantly improves the outcome by identifying individuals at this initial stage. The genetic basis of colorectal cancer, including the identification of patients at risk, plays a vital role in early diagnosis and intervention. Effective screening programs can reduce the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer by catching it at this highly treatable stage.

2. Stage I: Early-stage

Stage I colorectal cancer is characterized by the invasion of cancer cells into the layers of the colon or rectum but not beyond the muscular layer. This stage is considered early-stage cancer and has a relatively high survival rate. The prognosis for patients diagnosed at this stage is generally favorable, with a 5-year relative survival rate exceeding 90%. Early-stage colorectal cancer is often managed effectively with surgery alone, and the optimization of surgical techniques has significantly improved long-term survival rates. The identification of genetic markers and the understanding of the molecular changes that drive the progression from normal epithelium to carcinoma are essential for early detection and treatment.

3. Stage II: Localized spread

Stage II colorectal cancer involves the spread of cancer beyond the muscular layer of the colon or rectum to nearby tissues but not to the lymph nodes. This stage is considered localized spread and has a variable prognosis depending on specific risk factors. The 5-year survival rate for stage II disease is lower than that for stage I but still relatively high. Treatment often includes surgery, and in some cases, adjuvant chemotherapy may be recommended, especially for high-risk patients. Molecular markers such as microsatellite instability can help select patients for additional treatment, improving outcomes. Research continues to identify novel genes and biomarkers that drive the progression to stage II, providing potential targets for intervention.

4. Stage III: Regional spread

Stage III colorectal cancer is defined by the presence of cancer cells in the regional lymph nodes but not in distant organs. This stage is considered regional spread and has a more challenging prognosis compared to earlier stages. The 5-year survival rate for stage III disease is significantly lower than for stage I and II, but advances in treatment have improved outcomes. Treatment typically involves a combination of surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy, with oxaliplatin-based regimens being commonly used. The identification of patients at greatest risk and the use of targeted therapies are crucial for improving survival rates in stage III colorectal cancer. Research has identified specific driver genes that are associated with the progression to stage III, providing insights into potential therapeutic targets.

5. Stage IV: Metastatic

Stage IV colorectal cancer, or metastatic colorectal cancer, is characterized by the spread of cancer to distant organs such as the liver or lungs. This stage has the poorest prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate slightly greater than 10%. Treatment for stage IV disease often involves a multimodal approach, including surgery, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies. Advances in the treatment of metastatic disease have led to median survivals exceeding two years, and a minority of patients with oligometastatic disease may achieve long-term survival or even be cured with aggressive treatment. The identification of novel driver genes and biomarkers for stage IV progression is essential for developing targeted therapies and improving patient outcomes. The integration of targeted treatments with conventional cytotoxic drugs has resulted in incremental survival gains for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

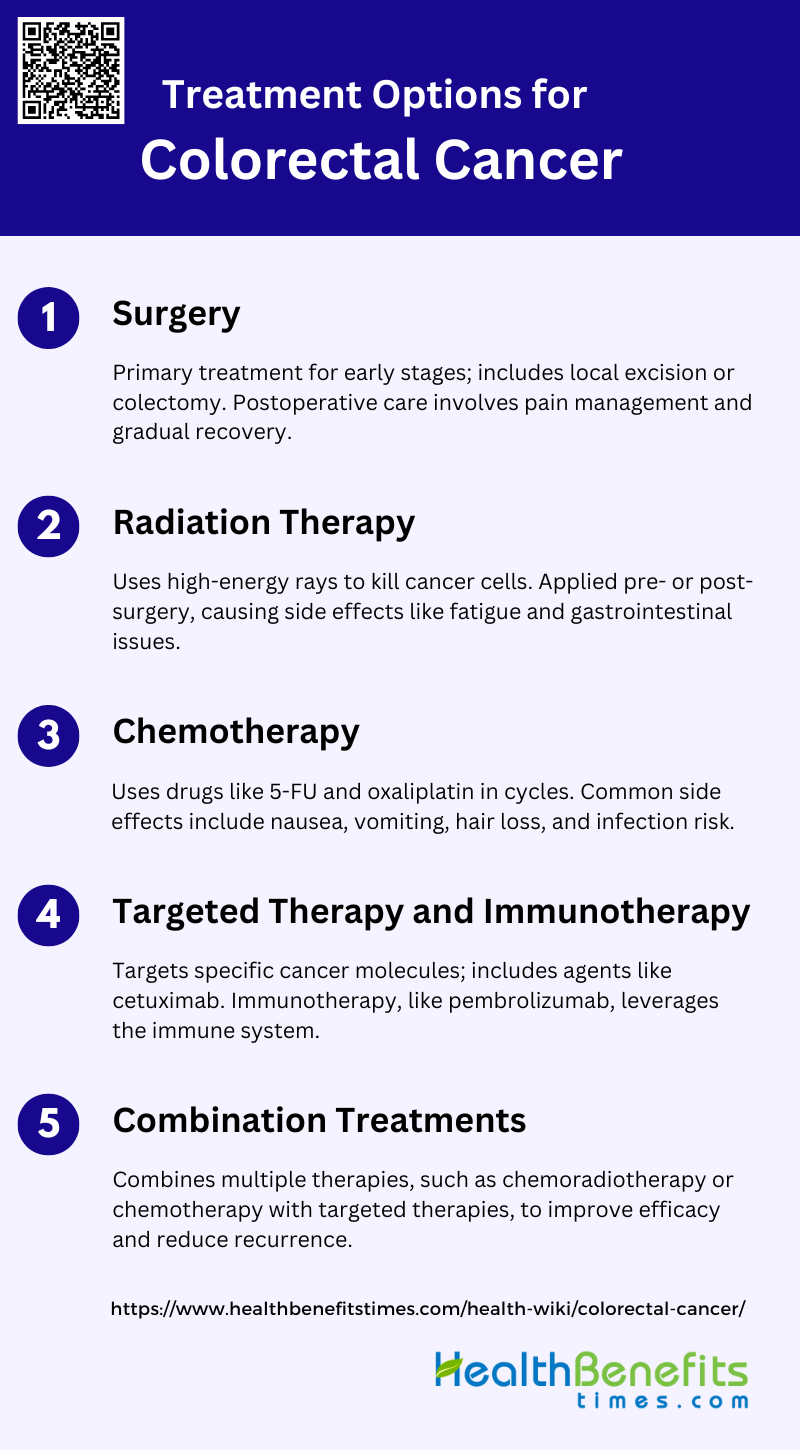

Treatment Options for Colorectal Cancer

Treating colorectal cancer involves various approaches tailored to the stage and specific characteristics of the disease. Early detection allows for more effective and less invasive treatments. Below are some common treatment options for colorectal cancer:

1. Surgery

Surgery is the primary curative treatment for colorectal cancer, especially in early stages. The types of surgery include local excision, where only the tumor is removed, and more extensive procedures like colectomy, which involves removing part or the entire colon. For rectal cancer, total mesorectal excision is often performed to ensure complete removal of cancerous tissues. Recovery from surgery varies but generally involves a hospital stay of several days, followed by weeks to months of recuperation at home. Postoperative care includes pain management, wound care, and gradual reintroduction of normal activities.

2. Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. It is often used preoperatively to reduce tumor size or postoperatively to eliminate residual cancer cells. The therapy works by damaging the DNA of cancer cells, which inhibits their ability to reproduce. Common side effects include fatigue, skin irritation at the treatment site, and gastrointestinal issues such as diarrhea and rectal bleeding. Long-term side effects can include bowel and bladder dysfunction. Despite these side effects, radiation therapy is a crucial component in the multimodal treatment of colorectal cancer.

3. Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy for colorectal cancer typically involves drugs like 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), oxaliplatin, and irinotecan. These drugs can be administered alone or in combination regimens such as FOLFOX (5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin). Treatment cycles usually last for two to three weeks, with a rest period in between to allow the body to recover. The number of cycles depends on the stage of cancer and the patient’s response to treatment. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, hair loss, and increased risk of infection due to lowered white blood cell counts.

4. Targeted therapy and immunotherapy

Targeted therapy aims at specific molecules involved in cancer growth and progression. Agents like cetuximab and bevacizumab target the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), respectively. Immunotherapy, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, leverages the body’s immune system to fight cancer. Pembrolizumab, for instance, is effective in tumors with high microsatellite instability. These therapies have shown significant effectiveness, particularly in metastatic colorectal cancer, by improving overall survival rates and reducing tumor size.

5. Combination treatments

Combination treatments involve using two or more therapeutic modalities to enhance efficacy. For instance, chemoradiotherapy combines chemotherapy and radiation therapy to maximize tumor reduction before surgery. Another example is the use of chemotherapy with targeted therapies like bevacizumab or cetuximab to treat metastatic colorectal cancer. These combinations are tailored based on the patient’s specific cancer characteristics and overall health. Studies have shown that combination treatments can improve survival rates and reduce recurrence, although they may also increase the risk of side effects.

Preventative Measures for Colorectal Cancer

Preventative measures for colorectal cancer are essential in reducing the risk and promoting early detection of this prevalent disease. By adopting a proactive approach, individuals can significantly lower their chances of developing colorectal cancer. The following list outlines key strategies and lifestyle changes that can help in the prevention of colorectal cancer:

1. Get Screened Regularly

Regular screening is a crucial preventative measure for colorectal cancer, as it allows for the early detection of cancer or preneoplastic lesions, significantly improving survival rates. Screening methods such as fecal occult blood tests and colonoscopy are effective, especially for individuals aged 50 years or older, those with hereditary colorectal cancer syndromes, and patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Despite the effectiveness of these methods, many eligible individuals remain unscreened, highlighting the need for increased awareness and accessibility of screening programs.

2. Maintain a Healthy Diet

A healthy diet plays a significant role in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer. Diets rich in fruits, vegetables, poultry, and fish, such as the Mediterranean diet, have been shown to lower the risk of colorectal cancer. Conversely, high intake of red and processed meats, refined grains, and sugars is associated with an increased risk. Additionally, certain dietary components like garlic, vitamin B6, and magnesium may offer protective benefits. While the role of dietary fiber remains debated, it is generally considered beneficial.

3. Exercise Regularly

Regular physical activity is strongly associated with a reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Engaging in moderate exercise not only helps in maintaining a healthy weight but also directly lowers cancer risk. Physical activity has been shown to protect against colon cancer, and its benefits extend to improving the quality of life and prognosis for patients already diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Therefore, incorporating regular exercise into daily routines is a highly recommended preventative measure.

4. Maintain a Healthy Weight

Maintaining a healthy weight is essential in reducing the risk of colorectal cancer. Obesity and abdominal fatness are convincing causes of colorectal cancer, and preventing weight gain through a balanced diet and regular physical activity can significantly lower the risk. Weight management is particularly important as it not only reduces cancer risk but also improves overall health and quality of life.

5. Don’t Smoke

Avoiding smoking is a critical preventative measure for colorectal cancer. Smoking is a well-established risk factor for many cancers, including colorectal cancer. Quitting smoking can significantly reduce the risk and improve overall health. Public health initiatives aimed at reducing smoking rates can have a substantial impact on lowering colorectal cancer incidence.

6. Limit Alcohol Intake

Limiting alcohol intake is another important strategy for reducing colorectal cancer risk. High alcohol consumption is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, and reducing intake can lower this risk. Both men and women should be mindful of their alcohol consumption, as even moderate drinking can contribute to cancer risk.

7. Manage Medical Conditions

Managing medical conditions such as inflammatory bowel diseases and diabetes is crucial in preventing colorectal cancer. Individuals with these conditions are at a higher risk and should be vigilant about regular screenings and maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Effective management of these conditions through medication, lifestyle changes, and regular medical check-ups can significantly reduce cancer risk.

8. Consider Aspirin

Aspirin has been shown to have a protective effect against colorectal cancer, particularly in high-risk populations. Regular use of aspirin can reduce the development of colonic adenomas and colorectal cancer, although the minimal effective dose remains unclear. However, the use of aspirin should be considered carefully due to potential side effects, and individuals should consult with their healthcare providers before starting any chemopreventive regimen.

9. Know Your Family History

Knowing your family history is vital in assessing the risk of colorectal cancer. Individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer or hereditary syndromes such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis are at increased risk and should undergo regular screenings. Understanding family history allows for early intervention and personalized preventative strategies, significantly reducing the risk of developing colorectal cancer.

Living with Colorectal Cancer

Living with colorectal cancer presents unique challenges and requires a comprehensive approach to manage the disease effectively. Understanding the impact on daily life and adopting strategies to cope can improve the quality of life for those affected. The following list provides essential tips and considerations for living with colorectal cancer:

1. Coping with Diagnosis

Receiving a diagnosis of colorectal cancer (CRC) can be an overwhelming experience, often accompanied by significant psychological distress. Patients frequently experience anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence, which can severely impact their quality of life (QoL). Effective coping strategies are essential to manage these emotional challenges. Supportive care interventions, such as the SurvivorCare program, have been shown to provide some relief, although their impact on psychological distress may be limited. Additionally, access to trained healthcare professionals and peer support can help patients navigate the initial shock and ongoing emotional burden of a CRC diagnosis.

2. Support Systems and Resources

Support systems play a crucial role in the well-being of CRC survivors. Social support from family, friends, and healthcare providers is associated with better health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Multidisciplinary care teams, including psychologists, social workers, and primary care physicians, are essential in addressing the diverse needs of CRC survivors. Programs like SurvivorCare, which include educational materials, needs assessments, and follow-up sessions, can enhance patient satisfaction with survivorship care, even if they do not significantly impact distress or QoL outcomes. Long-term support mechanisms, such as access to trained nurses and peer support groups, are also vital for ongoing care.

3. Managing Side Effects of Treatment

CRC treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation, often result in distressing short- and long-term side effects. Common issues include fatigue, sleep difficulties, gastrointestinal problems, urinary incontinence, and sexual dysfunction. Effective management of these symptoms is crucial for improving survivors’ QoL. Research indicates that symptom experiences are correlated with poor QoL and can interfere with daily life and relationships. Clinical practice guidelines recommend a healthy lifestyle, diet, and physical activity to manage these long-term symptoms, although evidence-based management strategies are still limited. Survivorship care plans that include regular follow-ups and targeted supportive care can help address these ongoing challenges.

4. Long-term Follow-up and Survivorship Care

Long-term follow-up and survivorship care are essential components of the CRC care continuum. Survivors often face persistent symptoms and functional impairments that require ongoing management. Comprehensive survivorship care should include surveillance for recurrence, genetic counseling, and management of psychosocial and physical late effects. Programs like SurvivorCare, which offer structured follow-up and individualized care plans, can improve patient satisfaction with care, even if they do not significantly impact clinical outcomes. Additionally, integrating recommendations for managing long-term symptoms into clinical practice guidelines can help healthcare providers offer better support to CRC survivors.