Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects the elderly population, characterized by a gradual decline in cognitive function, memory loss, and changes in behavior. It is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of cases. The disease is associated with the accumulation of abnormal protein deposits in the brain, specifically amyloid-beta plaques and tau tangles, which lead to neuronal death and brain atrophy. While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s is not fully understood, it is believed to result from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The disease typically progresses slowly over several years, with symptoms worsening over time and eventually interfering with daily activities and independence. Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s Disease, but ongoing research focuses on early detection, prevention, and potential treatments to slow its progression.

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that primarily affects the elderly population, characterized by a gradual decline in cognitive function, memory loss, and changes in behavior. It is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of cases. The disease is associated with the accumulation of abnormal protein deposits in the brain, specifically amyloid-beta plaques and tau tangles, which lead to neuronal death and brain atrophy. While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s is not fully understood, it is believed to result from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. The disease typically progresses slowly over several years, with symptoms worsening over time and eventually interfering with daily activities and independence. Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s Disease, but ongoing research focuses on early detection, prevention, and potential treatments to slow its progression.

Causes & risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a complex neurological disorder with multiple contributing factors. Understanding these causes and risk factors is crucial for early detection and prevention. Below are some of the primary causes and risk factors associated with Alzheimer’s disease:

1. Age and Family History

Age is the most significant risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease (AD), with the likelihood of developing the condition increasing substantially after the age of 65. Family history also plays a crucial role; individuals with a first-degree relative with AD are at a higher risk. Twin and family studies suggest that genetic factors contribute to approximately 80% of AD cases, with rare mutations in genes such as APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 being almost deterministic for early-onset familial AD. However, most AD cases are sporadic and influenced by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

2. Certain Genes

Genetic predisposition is a well-documented risk factor for AD. The APOE ε4 allele is the most significant genetic risk factor for late-onset AD, increasing the risk and lowering the age of onset. Mutations in the APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 genes are associated with early-onset familial AD, which accounts for less than 5% of all cases. Genome-wide association studies have identified additional candidate genes that may contribute to the disease’s complexity and heterogeneity.

3. Abnormal Protein Deposits in the Brain

The accumulation of abnormal protein deposits, such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) plaques and tau tangles, is a hallmark of AD pathology. The amyloid cascade hypothesis posits that the excessive build-up of Aβ leads to neuronal death and brain atrophy. Despite the central role of these proteins, treatments targeting Aβ have largely failed, suggesting that other mechanisms, including tau pathology and neuroinflammation, also contribute to the disease.

4. Other Risk and Environmental Factors

Several modifiable risk factors have been associated with AD. These include lifestyle factors such as diet, physical activity, and cognitive engagement. For instance, adherence to a Mediterranean diet, regular physical exercise, and cognitive stimulation are linked to a reduced risk of AD. Conversely, factors like smoking, head injuries, and exposure to environmental toxins such as air pollution and pesticides increase the risk. Vascular health is also crucial, with conditions like diabetes and hypertension being significant risk factors.

5. Immune System Problems

Emerging evidence suggests that immune system dysfunction plays a role in AD. Chronic inflammation and the activation of the innate immune system, particularly through pathways involving nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), are implicated in AD pathology. The interaction between genetic predispositions and environmental factors can exacerbate immune responses, leading to neuronal damage and progression of the disease. Understanding these mechanisms may open new avenues for therapeutic interventions targeting the immune system.

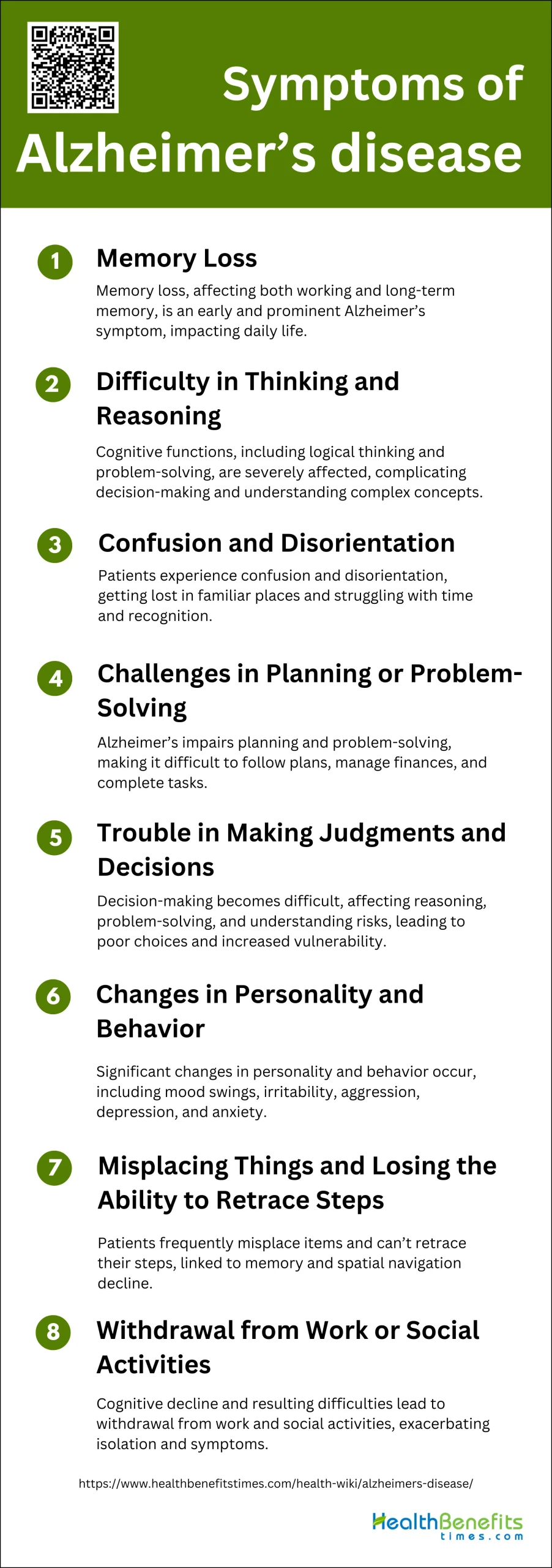

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease manifests through a range of cognitive and behavioral symptoms that progressively worsen over time. Recognizing these symptoms early can aid in timely diagnosis and management. Below are some of the common symptoms associated with Alzheimer’s disease:

1. Memory Loss

Memory loss is one of the earliest and most prominent symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Patients often experience difficulties with both working memory and long-term declarative memory, which significantly impacts their daily lives. This memory impairment is closely linked to structural and functional changes in the brain, particularly in areas such as the hippocampus and the default mode network. The progressive nature of memory loss in AD patients can lead to challenges in performing routine tasks and recognizing familiar people and places. Neuropsychological testing remains a core component in diagnosing AD due to its ability to identify specific memory deficits.

2. Difficulty in Thinking and Reasoning

Alzheimer’s disease also severely affects cognitive functions, including thinking and reasoning abilities. Patients often struggle with tasks that require logical thinking, problem-solving, and understanding complex concepts. These cognitive impairments are due to the degeneration of neurons and the disruption of neural communication caused by amyloid-β plaques and tau tangles in the brain. As the disease progresses, these difficulties become more pronounced, making it challenging for patients to make decisions and understand the consequences of their actions. This decline in cognitive function is a hallmark of AD and significantly impacts the quality of life of those affected.

3. Confusion and Disorientation

Confusion and disorientation are common symptoms in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. These symptoms often manifest as getting lost in familiar places, losing track of time, and being unable to recognize familiar faces or objects. The underlying cause of these symptoms is the progressive degeneration of brain cells, particularly in the hippocampus, which is crucial for spatial memory and navigation. As the disease advances, patients may experience increased episodes of confusion and disorientation, which can lead to safety concerns and require constant supervision. These symptoms are distressing for both patients and their caregivers, highlighting the need for effective management strategies.

4. Challenges in Planning or Problem-Solving

Alzheimer’s disease impairs an individual’s ability to plan and solve problems. Patients often find it difficult to follow a plan, manage finances, or complete tasks that require multiple steps. This is due to the disruption of neural circuits involved in executive functions, which are essential for organizing and executing complex tasks. The decline in these cognitive abilities can lead to significant challenges in daily living, making it difficult for patients to maintain independence. Understanding the specific neural mechanisms underlying these deficits is crucial for developing targeted interventions to support patients in managing their daily activities.

5. Trouble in Making Judgments and Decisions

Making judgments and decisions becomes increasingly difficult for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. This symptom is closely related to the decline in cognitive functions such as reasoning, problem-solving, and executive function. Patients may struggle with making choices, understanding risks, and evaluating the consequences of their actions. This impairment can lead to poor decision-making and increased vulnerability to exploitation or accidents. The progressive nature of AD means that these difficulties worsen over time, necessitating the involvement of caregivers to assist with decision-making and ensure the safety and well-being of the patient.

6. Changes in Personality and Behavior

Alzheimer’s disease often leads to significant changes in personality and behavior. Patients may exhibit mood swings, increased irritability, aggression, depression, and anxiety. These neuropsychiatric symptoms, also known as behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), are thought to result from the degeneration of brain regions involved in regulating emotions and behavior. The presence of amyloid-β plaques and tau tangles disrupts neural communication, leading to these behavioral changes. Managing these symptoms is challenging and requires a combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions to improve the quality of life for patients and their caregivers.

7. Misplacing Things and Losing the Ability to Retrace Steps

Misplacing items and losing the ability to retrace steps are common symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Patients often place objects in unusual locations and are unable to remember where they left them, leading to frustration and confusion. This symptom is related to the decline in memory and spatial navigation abilities, which are affected early in the disease process. The hippocampus, a critical region for forming and retrieving memories, is particularly vulnerable to the pathological changes seen in AD. As the disease progresses, these difficulties become more pronounced, further complicating daily living and increasing dependence on caregivers.

8. Withdrawal from Work or Social Activities

Individuals with Alzheimer’s disease often withdraw from work or social activities. This withdrawal can be attributed to the cognitive decline and the resulting difficulties in communication, memory, and executive function. Patients may feel embarrassed or frustrated by their inability to keep up with conversations or perform tasks they once found easy. Additionally, changes in personality and behavior, such as increased irritability or depression, can contribute to social withdrawal. This isolation can exacerbate the symptoms of AD and negatively impact the mental health and well-being of patients, highlighting the importance of social support and engagement in managing the disease.

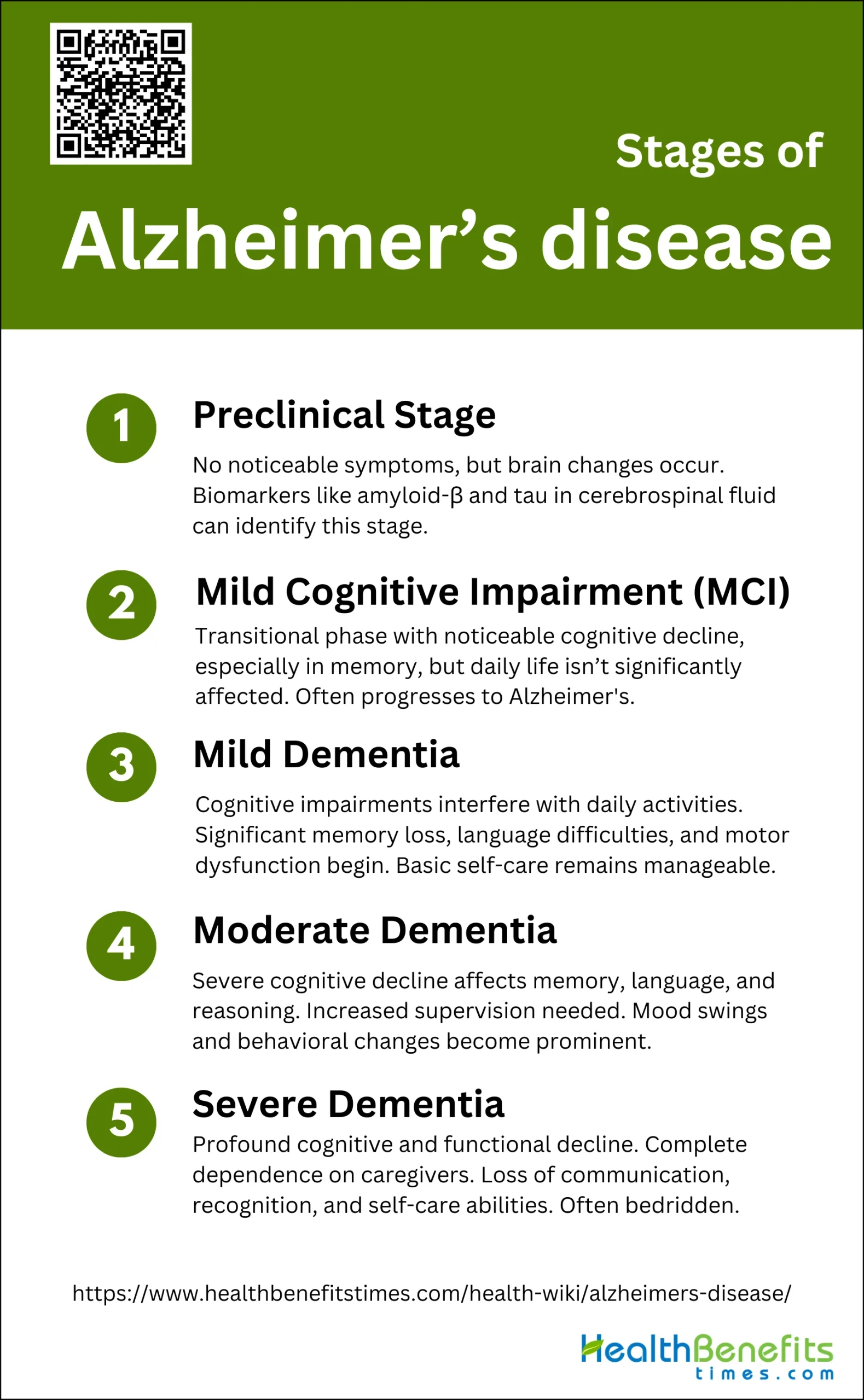

Stages of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease progresses through distinct stages, each marked by increasing cognitive and functional decline. Recognizing these stages can help in planning care and interventions. Below are the primary stages of Alzheimer’s disease:

1. Preclinical Stage

The preclinical stage of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the absence of noticeable symptoms, despite the presence of pathological changes in the brain. This stage can last for many years, providing a critical window for potential therapeutic interventions. Biomarkers such as amyloid-β and tau proteins in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are often used to identify individuals at this stage. Research has shown that changes in CSF biochemistry related to brain oxidative defense and neurometallomics might provide powerful diagnostic tools during this phase. The National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association have proposed a framework to study this stage, aiming to predict the risk of progression to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia.

2. Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI)

Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) is considered a transitional phase between normal aging and early-stage AD. Individuals with MCI exhibit noticeable cognitive decline, particularly in memory, but these changes are not severe enough to interfere significantly with daily life. Studies have shown that MCI often progresses to AD, with annual conversion rates estimated between 10% to 15%. Structural MRI has been used to assess brain atrophy in MCI patients, although its diagnostic accuracy is moderate. Additionally, increased serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been observed in MCI patients, suggesting an upregulation of neuroprotective mechanisms.

3. Mild Dementia

In the mild dementia stage of AD, cognitive impairments become more pronounced and begin to interfere with daily activities. Patients often experience significant memory loss, difficulties with language, and challenges in performing complex tasks. Despite these impairments, individuals can still manage basic self-care and live independently, although they may require some supervision. Motor dysfunction also starts to become evident, as measured by tests like the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test, which shows a decline in functional mobility in mild AD patients compared to healthy elderly individuals. This stage marks the beginning of more noticeable and impactful symptoms of AD.

4. Moderate Dementia

During the moderate dementia stage, cognitive decline becomes more severe, affecting multiple domains such as memory, language, reasoning, and perception. Patients often require increased supervision and assistance with daily activities. Non-cognitive symptoms, including mood swings, confusion, and behavioral changes, become more prominent, placing significant stress on caregivers. Studies have shown that motor dysfunction continues to worsen, with patients exhibiting greater impairments in mobility and coordination. This stage is marked by a substantial loss of independence and a greater need for comprehensive care and support.

5. Severe Dementia

Severe dementia represents the final stage of AD, characterized by profound cognitive and functional decline. Patients lose the ability to communicate effectively, recognize loved ones, and perform basic self-care tasks. They become completely dependent on caregivers for all aspects of daily living. Neurological disturbances, such as difficulty swallowing and incontinence, are common, and patients are often bedridden. The life expectancy of individuals in this stage is significantly reduced, but modern symptomatic treatments aim to prolong the period of relative well-being and alleviate suffering. This stage underscores the devastating impact of AD on both patients and their families.

What is the Difference between Alzheimer’s and Dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term that encompasses a variety of diseases and conditions characterized by the progressive decline in cognitive function, memory, and behavior due to the malfunction or death of neurons in the brain. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60 to 80% of cases, and is specifically associated with age-related cognitive and functional decline, marked by the accumulation of beta-amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau protein tangles in the brain. While dementia can result from various causes such as vascular issues or chronic alcoholism, Alzheimer’s disease is distinguished by its unique neuropathological features and its initial impact on the ability to encode and store new memories. Alzheimer’s and Dementia share overlapping symptoms, but Alzheimer’s disease has a distinct progression and underlying biological mechanisms that differentiate it from other types of dementia.

Difference between Alzheimer’s and dementia

| Aspect | Dementia | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| Definition | An umbrella term for a set of symptoms affecting memory, communication, and thinking. | A degenerative brain disease that is the most common cause of dementia. |

| Symptoms | Memory loss, difficulty in communication, impaired judgment, disorientation, changes in mood. | Memory loss, confusion, difficulty with language and speech, disorientation, changes in mood and behavior. |

| Progression | Varies depending on the cause; can be reversible or irreversible. | Typically slow and progressive; symptoms worsen over time. |

| Causes | Various causes including Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, etc. | Caused by the abnormal build-up of proteins in and around brain cells. |

| Diagnosis | Based on clinical assessment, medical history, and cognitive testing; sometimes brain scans. | Based on clinical assessment, medical history, cognitive testing, and sometimes biomarkers or brain imaging. |

| Treatment | Depends on the cause; may include medications, cognitive therapy, and management of symptoms. | No cure, but treatments can slow progression and manage symptoms; includes medications and supportive therapies. |

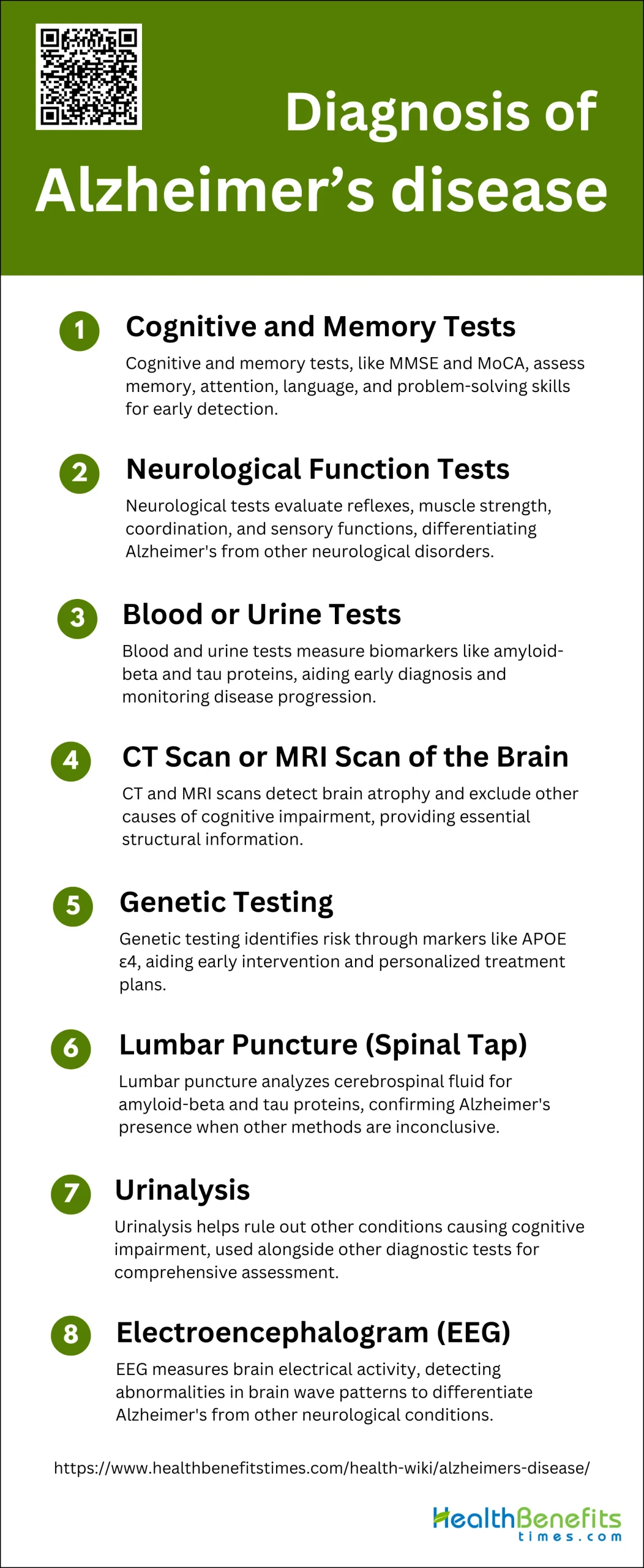

Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

Diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease involves a comprehensive evaluation of medical history, cognitive tests, and brain imaging. Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective management and treatment planning. Below are the primary methods used to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease:

1. Cognitive and Memory Tests

Cognitive and memory tests are fundamental in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). These tests assess various cognitive functions, including memory, attention, language, and problem-solving skills. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) are commonly used tools. These tests help identify cognitive impairments that may indicate the early stages of AD. Studies have shown that cognitive decline, particularly in memory, is a hallmark of AD, and these tests are crucial for early detection and monitoring disease progression.

2. Neurological Function Tests

Neurological function tests are essential in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease as they help evaluate the nervous system’s overall health. These tests include assessments of reflexes, muscle strength, coordination, and sensory functions. Neurological examinations can reveal signs of neurological disorders that may mimic or coexist with AD. For instance, abnormalities in motor function or reflexes might suggest other neurodegenerative conditions. Comprehensive neurological assessments, combined with cognitive tests, provide a more accurate diagnosis of AD and help differentiate it from other neurological disorders.

3. Blood or Urine Tests

Blood and urine tests are increasingly being explored for their potential in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. Biomarkers such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau proteins in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are of particular interest. Studies have shown that elevated levels of plasma P-tau181 and altered Aβ42/40 ratios in blood can predict amyloid deposition in the brain, which is characteristic of AD. These non-invasive tests offer a promising approach for early diagnosis and monitoring disease progression, making them valuable tools in clinical practice.

4. CT Scan or MRI Scan of the Brain

CT and MRI scans are critical imaging tools used in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease. Structural MRI, in particular, is valuable for detecting brain atrophy, especially in the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe, which are early indicators of AD. MRI can also help exclude other causes of cognitive impairment, such as tumors or vascular lesions. Although MRI alone may not be sufficient for a definitive diagnosis, it provides essential information about brain structure and helps in the early detection and differentiation of AD from other dementias.

5. Genetic Testing

Genetic testing can identify individuals at higher risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease, particularly those with a family history of the condition. The presence of certain genetic markers, such as the APOE ε4 allele, is associated with an increased risk of AD. Genetic testing can provide valuable information for early intervention and personalized treatment plans. However, it is essential to consider the ethical implications and psychological impact of genetic testing, as it may affect individuals’ decisions regarding their health and lifestyle.

6. Lumbar Puncture (Spinal Tap)

A lumbar puncture, or spinal tap, is a procedure used to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for analysis. This test can measure levels of amyloid-beta and tau proteins, which are biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Studies have shown that low levels of CSF Aβ42 and elevated levels of tau proteins are indicative of AD. Although invasive, lumbar puncture provides valuable diagnostic information and can help confirm the presence of AD, especially in cases where other diagnostic methods are inconclusive.

7. Urinalysis

Urinalysis is not commonly used as a primary diagnostic tool for Alzheimer’s disease. However, it can help rule out other conditions that may cause cognitive impairment, such as infections or metabolic disorders. While research is ongoing to identify potential urinary biomarkers for AD, current evidence suggests that urinalysis alone is insufficient for diagnosing the disease. It is typically used in conjunction with other diagnostic tests to provide a comprehensive assessment of a patient’s health.

8. Electroencephalogram (EEG)

An electroencephalogram (EEG) measures electrical activity in the brain and can help diagnose Alzheimer’s disease by detecting abnormalities in brain wave patterns. Studies have shown that patients with AD often exhibit changes in EEG patterns, such as a decrease in alpha waves and an increase in theta and delta waves. While EEG is not a definitive diagnostic tool for AD, it can provide valuable information about brain function and help differentiate AD from other neurological conditions, such as epilepsy or sleep disorders.

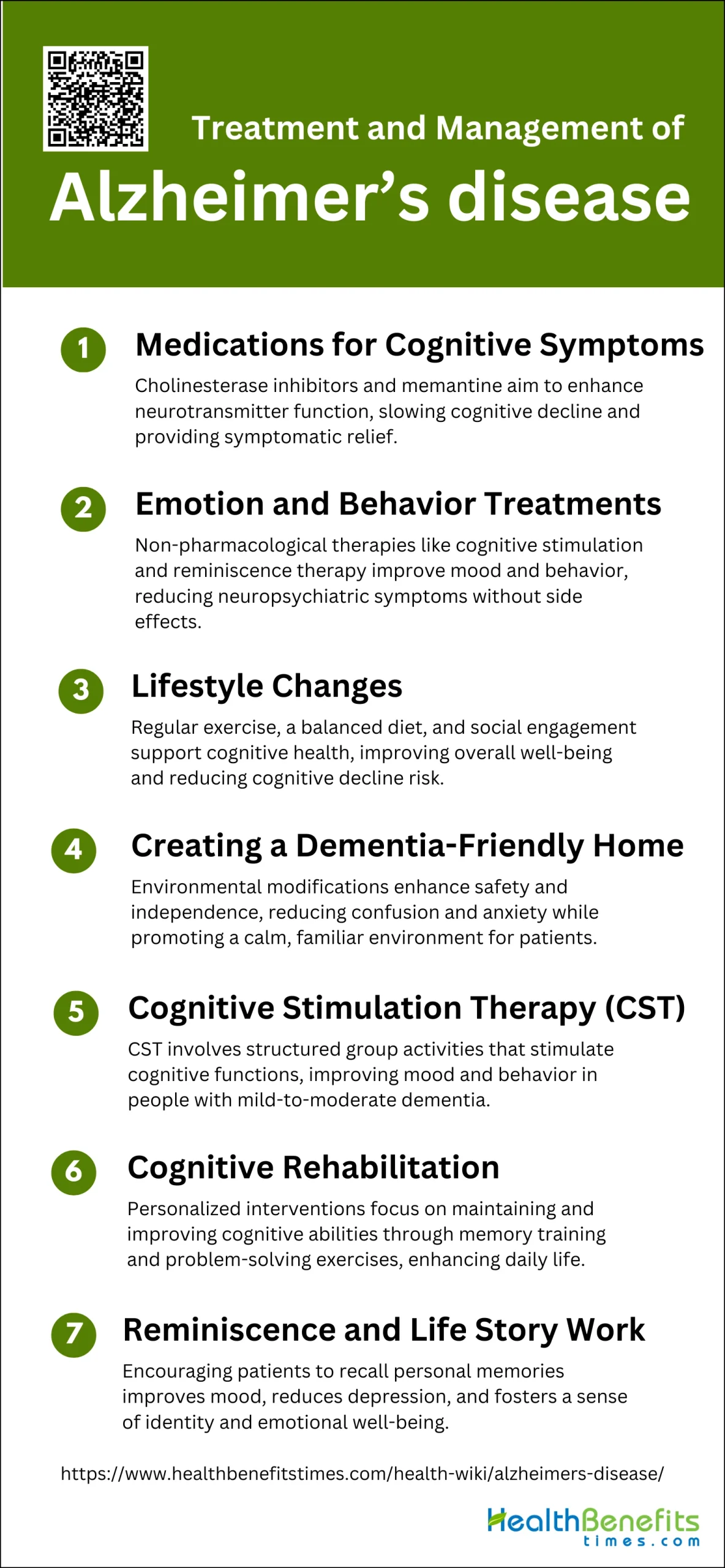

Treatment and Management of Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive neurological disorder that affects memory, thinking, and behavior. Effective treatment and management strategies are crucial for improving the quality of life for those affected. Below are some key approaches to managing Alzheimer’s disease:

1. Medications for Cognitive Symptoms

Medications for cognitive symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease primarily include cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) and the NMDA receptor antagonist memantine. These drugs aim to enhance neurotransmitter function and slow cognitive decline. Cholinesterase inhibitors work by increasing levels of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter associated with memory and learning, while memantine regulates glutamate activity to prevent excitotoxicity. Although these medications do not cure Alzheimer’s, they can provide symptomatic relief and improve quality of life for some patients.

2. Emotion and Behavior Treatments

Emotion and behavior treatments for Alzheimer’s disease often involve non-pharmacological interventions such as cognitive stimulation therapy (CST) and reminiscence therapy (RT). CST has been shown to stabilize cognitive function and improve mood and behavior in patients with mild-to-moderate dementia. RT, which involves recalling past experiences, has demonstrated efficacy in reducing depression and enhancing quality of life. These therapies can be administered in group or individual settings and are valuable in managing neuropsychiatric symptoms without the side effects associated with pharmacological treatments.

3. Lifestyle Changes

Lifestyle changes play a crucial role in managing Alzheimer’s disease. Regular physical exercise, a balanced diet, and social engagement are recommended to support cognitive health. Exercise has been shown to improve cognitive function and reduce the risk of cognitive decline. A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins, such as the Mediterranean diet, is associated with better cognitive outcomes. Social activities and mental stimulation, including hobbies and group activities, can also help maintain cognitive function and improve overall well-being.

4. Creating a Dementia-Friendly Home

Creating a dementia-friendly home involves making environmental modifications to enhance safety and independence for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. This includes simplifying the layout, using clear signage, and ensuring adequate lighting to reduce confusion and prevent accidents. Safety measures such as installing grab bars, removing tripping hazards, and using locks on cabinets containing dangerous items are essential. Additionally, creating a calm and familiar environment with personal items and memory aids can help reduce anxiety and improve quality of life.

5. Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST)

Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) is an evidence-based intervention designed to improve cognitive function and quality of life in people with dementia. CST involves structured group activities that stimulate thinking, concentration, and memory. Studies have shown that CST can stabilize cognitive function and provide short-term benefits in mood and behavior, which are often maintained over the long term. CST is widely recommended and implemented in various countries as part of dementia care services.

6. Cognitive Rehabilitation

Cognitive rehabilitation focuses on helping individuals with Alzheimer’s disease maintain and improve their cognitive abilities through personalized interventions. Techniques include memory training, problem-solving exercises, and the use of compensatory strategies to manage daily tasks. Cognitive rehabilitation aims to enhance the individual’s ability to perform everyday activities and improve their quality of life. Although evidence for its efficacy is still emerging, cognitive rehabilitation is considered a valuable component of a comprehensive dementia care plan.

7. Reminiscence and Life Story Work

Reminiscence and life story work involve encouraging individuals with Alzheimer’s disease to recall and share personal memories and experiences. This therapeutic approach can improve mood, reduce depression, and enhance the quality of life by fostering a sense of identity and continuity. Reminiscence therapy has been shown to support global cognition and emotional well-being, making it a beneficial non-pharmacological intervention for dementia care. Life story work, which involves creating a personal history book, can also strengthen relationships between patients and caregivers, providing emotional support and enhancing communication.

Preventions of Alzheimer’s disease

Preventing Alzheimer’s disease involves adopting a healthy lifestyle and engaging in activities that promote brain health. While there is no guaranteed way to prevent the disease, certain strategies can help reduce the risk. Below are some key preventive measures:

1. Stay Mentally Active

Staying mentally active is a crucial strategy in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Engaging in cognitive activities such as reading, puzzles, and learning new skills can help maintain high levels of cognition and functional integrity. Studies have shown that cognitive training and “brain fitness” interventions can have sustained effects on cognitive function, lasting up to 10 years or more. Additionally, lifelong engagement in cognitively stimulating activities has been associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Therefore, incorporating mental exercises into daily routines can be a beneficial preventive measure against Alzheimer’s disease.

2. Getting Regular Exercise

Regular physical exercise is another important preventive measure for Alzheimer’s disease. Exercise has been shown to modulate amyloid β turnover, reduce inflammation, and improve cerebral blood flow, all of which are beneficial for brain health. Moreover, older adults who engage in regular physical activity are more likely to maintain their cognitive functions. A combination of physical exercise and a healthy diet has been highlighted as a promising strategy to prevent cognitive decline and delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, incorporating regular physical activity into one’s lifestyle is essential for reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

3. Maintain an Active Social Life

Maintaining an active social life is also crucial in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Social engagement and cognitive stimulation through social interactions can help delay or prevent the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Behavioral interventions that include social activities have been shown to support healthy cognitive aging and reduce the risk of dementia. Additionally, lifelong engagement in socially stimulating activities can counteract brain aging and contribute to brain resilience. Therefore, fostering strong social connections and participating in social activities can be an effective strategy to prevent Alzheimer’s disease.

4. Varied and Healthful Diet

A varied and healthful diet plays a significant role in the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Nutritional recommendations for preventing neurodegenerative diseases include the consumption of vegetables, fruits, cereals, legumes, vegetable oils, and fish, while dairy products and meat should be consumed in moderation. The Mediterranean and Asian diets, which are rich in these components, have been associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Adequate nutrition, combined with physical activity, has been shown to minimize the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Therefore, adopting a varied and healthful diet is essential for reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

5. Maintain a Healthy Cardiovascular System

Maintaining a healthy cardiovascular system is vital for preventing Alzheimer’s disease. Cardiovascular health is closely linked to brain health, and conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity are known risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Preventing and treating cardiovascular morbidity can protect the brain and reduce the risk of cognitive decline. A multifactorial intervention that includes regular exercise, a healthy diet, and the management of vascular risk factors has been suggested as a promising strategy for preventing cognitive decline. Therefore, maintaining a healthy cardiovascular system is crucial for reducing the risk of Alzheimer’s disease.