Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), is a condition that occurs when individuals ascend to high altitudes, typically above 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), without proper acclimatization. It is characterized by nonspecific symptoms such as headache, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and sleep disturbances, which result from the body’s inability to adapt quickly to the lower oxygen levels found at higher elevations. In severe cases, AMS can progress to life-threatening conditions like high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), which involve swelling in the brain and fluid accumulation in the lungs, respectively. Early recognition and treatment, including descent to lower altitudes and administration of oxygen, are crucial for preventing serious complications.

Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), is a condition that occurs when individuals ascend to high altitudes, typically above 2,500 meters (8,200 feet), without proper acclimatization. It is characterized by nonspecific symptoms such as headache, dizziness, nausea, fatigue, and sleep disturbances, which result from the body’s inability to adapt quickly to the lower oxygen levels found at higher elevations. In severe cases, AMS can progress to life-threatening conditions like high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE), which involve swelling in the brain and fluid accumulation in the lungs, respectively. Early recognition and treatment, including descent to lower altitudes and administration of oxygen, are crucial for preventing serious complications.

Types of Altitude Sickness

It is important to recognize the different types of altitude sickness to ensure proper treatment and prevention. Here are the main types:

1. Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS)

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) is a common condition that affects individuals who ascend to high altitudes too quickly without proper acclimatization. Symptoms typically include headache, nausea, dizziness, fatigue, and difficulty sleeping. AMS is primarily caused by the reduced oxygen levels at high altitudes, which can lead to hypoxia and subsequent oxidative stress. Studies have shown that oxidative stress markers such as malondialdehyde (MDA) increase, while antioxidant activities like superoxide dismutase (SOD) and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) decrease in individuals with AMS.

2. High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE)

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE) is a severe and potentially life-threatening condition characterized by the accumulation of fluid in the lungs. It is a non-cardiogenic form of pulmonary edema that occurs due to excessive hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, leading to increased capillary pressure and leakage of fluid into the alveolar spaces. Symptoms include shortness of breath, cough, chest tightness, and frothy sputum. HAPE is often associated with high concentrations of proteins and cells in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, indicating increased permeability of the pulmonary capillaries. The condition can develop rapidly and requires immediate descent to lower altitudes and medical intervention to prevent fatal outcomes.

3. High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE)

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE) is a severe and potentially fatal condition that occurs due to the swelling of the brain at high altitudes. It is often considered the end-stage of Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) and is characterized by symptoms such as severe headache, ataxia, confusion, and loss of consciousness. HACE is believed to result from increased intracranial pressure due to vasogenic and cytotoxic edema, where the blood-brain barrier becomes permeable, allowing fluid to leak into the brain tissue. Neuroimaging studies have shown that HACE is associated with increased brain water content and changes in diffusion indices within white matter. Immediate descent and medical treatment are crucial to prevent permanent neurological damage or death.

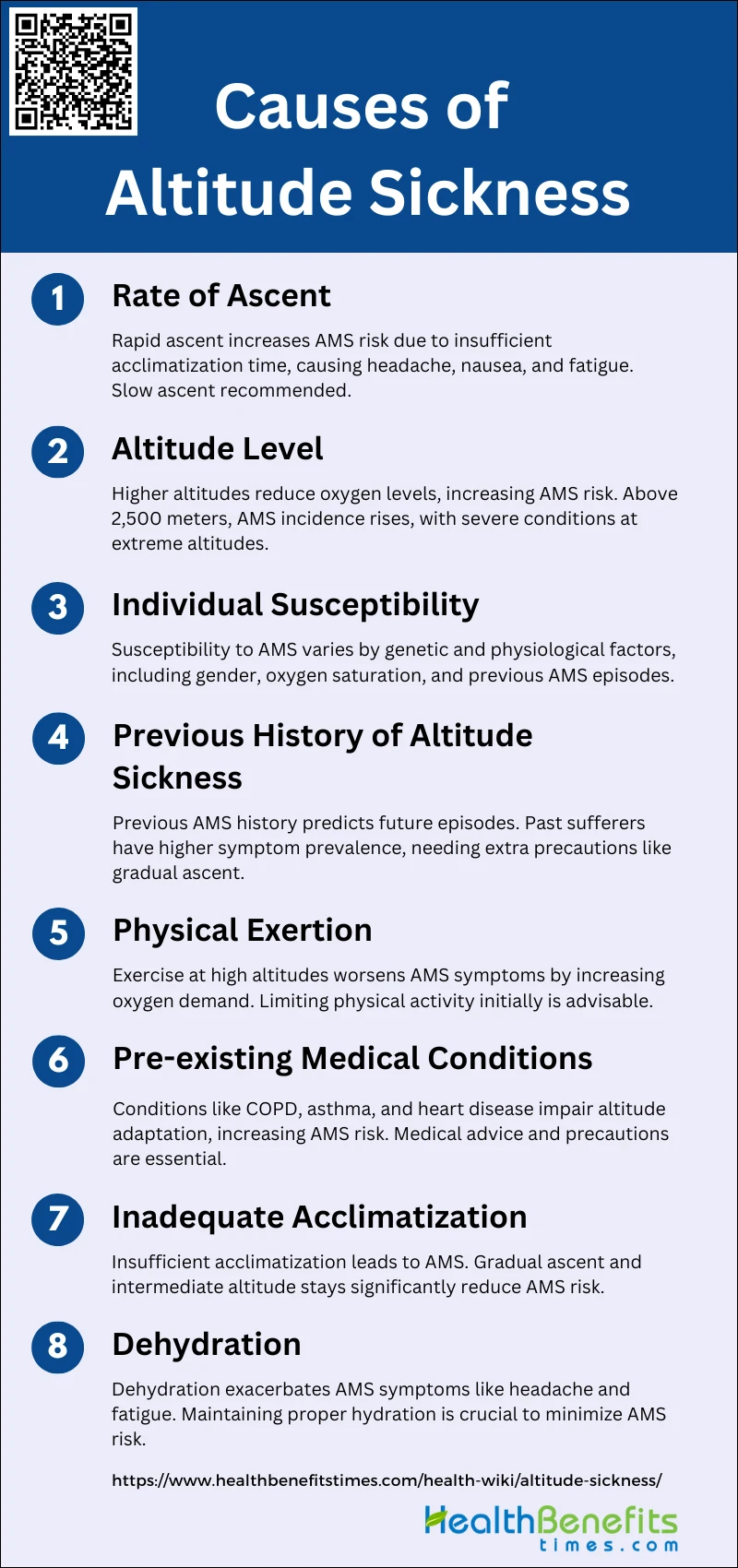

Causes of Altitude Sickness

This condition can affect anyone, regardless of age or fitness level, and is typically experienced at altitudes above 8,000 feet (2,400 meters). The primary causes of altitude sickness include:

1. Rate of Ascent

The rate of ascent is a critical factor in the development of acute mountain sickness (AMS). Rapid ascent to high altitudes significantly increases the risk of AMS due to insufficient time for acclimatization. Studies have shown that individuals who ascend quickly, such as by air travel, have a higher incidence of AMS compared to those who ascend gradually by hiking or driving. The lack of gradual acclimatization leads to a steeper increase in AMS symptoms, including headache, nausea, and fatigue. Therefore, a slower ascent rate is recommended to allow the body to adjust to the reduced oxygen levels at higher altitudes.

2. Altitude Level

The altitude level itself is a major determinant of AMS risk. Higher altitudes are associated with lower oxygen levels, which can lead to hypoxemia and subsequent AMS symptoms. Research indicates that the incidence of AMS increases significantly at elevations above 2,500 meters, with symptoms becoming more severe as altitude increases. At extreme altitudes, such as above 4,000 meters, the risk of life-threatening conditions like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) also rises. Therefore, understanding the altitude level and preparing accordingly is crucial for preventing AMS.

3. Individual Susceptibility

Individual susceptibility to AMS varies widely and is influenced by genetic and physiological factors. Some people are naturally more prone to AMS due to differences in their body’s response to hypoxia. Studies have shown that factors such as gender, with women being more susceptible, and physiological responses like lower oxygen saturation levels during exercise at low altitudes can predict AMS development. Additionally, a history of previous AMS episodes can indicate higher susceptibility. Recognizing individual susceptibility can help in taking preventive measures, such as pre-acclimatization or medication.

4. Previous History of Altitude Sickness

A previous history of altitude sickness is a strong predictor of future AMS episodes. Individuals who have experienced AMS before are more likely to develop it again upon re-exposure to high altitudes. This is supported by studies showing that past AMS sufferers have a higher prevalence of symptoms during subsequent high-altitude exposures. Therefore, individuals with a history of AMS should take extra precautions, such as gradual ascent and possibly using prophylactic medications like acetazolamide.

5. Physical Exertion

Physical exertion at high altitudes can exacerbate AMS symptoms. Exercise increases the body’s oxygen demand, which can worsen hypoxemia and lead to more severe AMS symptoms. Research has demonstrated that individuals who engage in physical activity shortly after ascending to high altitudes experience higher AMS severity compared to those who remain sedentary. This is due to exercise-induced arterial hypoxemia and fluid shifts that can aggravate AMS. Therefore, limiting physical exertion during the initial period of high-altitude exposure is advisable.

6. Pre-existing Medical Conditions

Pre-existing medical conditions, particularly those affecting the cardiovascular and respiratory systems, can increase the risk of AMS. Conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and heart disease can impair the body’s ability to adapt to reduced oxygen levels at high altitudes. Individuals with these conditions should seek medical advice before traveling to high altitudes and may require additional precautions, such as slower ascent rates and the use of supplemental oxygen.

7. Inadequate Acclimatization

Inadequate acclimatization is a primary cause of AMS. The body needs time to adjust to the lower oxygen levels at high altitudes, and insufficient acclimatization can lead to the development of AMS symptoms. Studies have shown that proper acclimatization, which includes gradual ascent and spending time at intermediate altitudes, significantly reduces the risk of AMS. Acclimatization strategies such as staged ascents and pre-acclimatization using hypoxic tents can help in preventing AMS.

8. Dehydration

Dehydration can contribute to the development of AMS by exacerbating symptoms such as headache and fatigue. High altitudes can increase fluid loss through respiration and perspiration, leading to dehydration if fluid intake is not adequately maintained. Research indicates that maintaining proper hydration is essential for minimizing AMS symptoms. Therefore, individuals traveling to high altitudes should ensure they drink sufficient fluids to stay hydrated and reduce the risk of AMS.

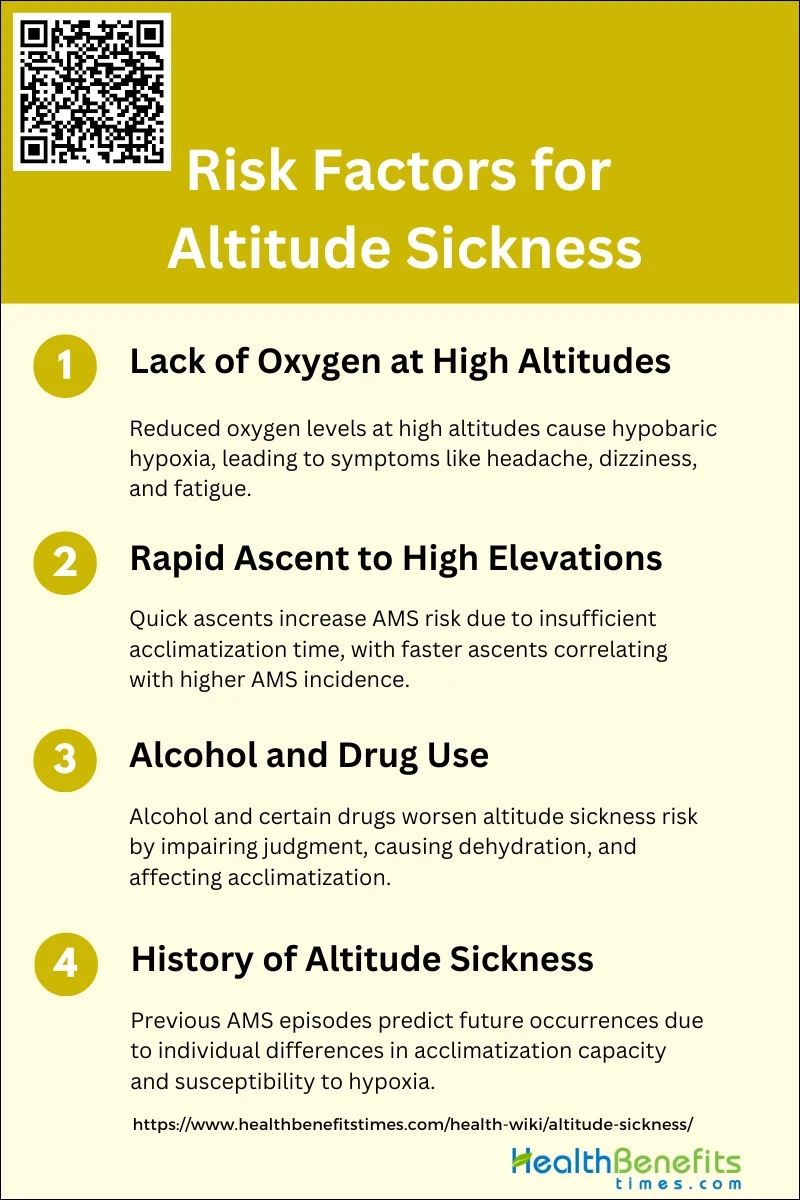

Risk factors for Altitude Sickness

These factors include the rate of ascent, altitude reached, and individual susceptibility. Understanding these risk factors can help in planning and taking preventive measures. Key risk factors include:

1. Lack of oxygen at high altitudes

At high altitudes, the partial pressure of oxygen decreases, leading to hypobaric hypoxia, which is a significant risk factor for altitude sickness. The human body struggles to acclimatize to the reduced oxygen levels, resulting in symptoms such as headache, dizziness, fatigue, and nausea, collectively known as acute mountain sickness (AMS). Studies have shown that individuals who rapidly ascend to high altitudes without adequate acclimatization are at a higher risk of developing AMS due to the sudden drop in oxygen availability. Effective acclimatization strategies, such as gradual ascent and pre-acclimatization, are crucial in mitigating these risks.

2. Rapid ascent to high elevations

Rapid ascent to high elevations is a well-documented risk factor for altitude sickness. When individuals ascend quickly, their bodies do not have sufficient time to acclimatize to the lower oxygen levels, leading to a higher incidence of AMS. Research indicates that the rate of ascent significantly impacts the likelihood of developing AMS, with faster ascents correlating with higher AMS incidence. For instance, a study found that individuals who ascended rapidly to altitudes above 3000 meters experienced a higher prevalence of AMS compared to those who ascended more gradually. Therefore, a slower ascent is recommended to allow the body to adjust to the changing altitude.

3. Alcohol and drug (medical and nonmedical) use

The consumption of alcohol and certain drugs can exacerbate the risk of altitude sickness. Alcohol, in particular, can impair judgment and exacerbate dehydration, which can worsen the symptoms of AMS. Additionally, some medications, both prescribed and recreational, may interfere with the body’s ability to acclimatize to high altitudes. For example, sedatives and sleeping pills can depress respiratory function, further reducing oxygen intake and increasing the risk of AMS. Conversely, certain prophylactic medications like acetazolamide and dexamethasone have been shown to help prevent AMS by enhancing acclimatization.

4. History of altitude sickness

A history of altitude sickness is a significant predictor of future episodes. Individuals who have previously experienced AMS are more likely to develop it again when exposed to similar altitudes. This predisposition is likely due to individual physiological differences in acclimatization capacity and susceptibility to hypoxia. Studies have shown that a prior history of AMS increases the risk of recurrence, emphasizing the importance of preventive measures for these individuals, such as gradual ascent and the use of prophylactic medications. Awareness and preparation are crucial for those with a known history of altitude sickness to mitigate the risks during future high-altitude exposures.

Symptoms of Altitude Sickness

Altitude sickness can manifest in various ways, affecting individuals who ascend to high altitudes too quickly. Recognizing the symptoms early is crucial for effective treatment and prevention. Here are some common symptoms:

- Headache: Headache is the most common and predominant symptom of acute mountain sickness (AMS) and high-altitude headache (HAH). It is often accompanied by other symptoms and can range from mild to severe.

- Dizziness and Lightheadedness: Dizziness and lightheadedness are frequently reported symptoms of AMS. These symptoms can affect balance and coordination, making physical activities challenging.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Nausea, often progressing to vomiting, is a significant symptom of AMS. It can severely impact a person’s ability to eat and maintain hydration, exacerbating the condition.

- Fatigue and Lethargy: Fatigue and lethargy are common symptoms that can limit physical activity and overall energy levels. These symptoms are often reported alongside headache and dizziness.

- Sleep Disturbance: Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, are frequently associated with AMS. These disturbances can further contribute to fatigue and overall discomfort at high altitudes.

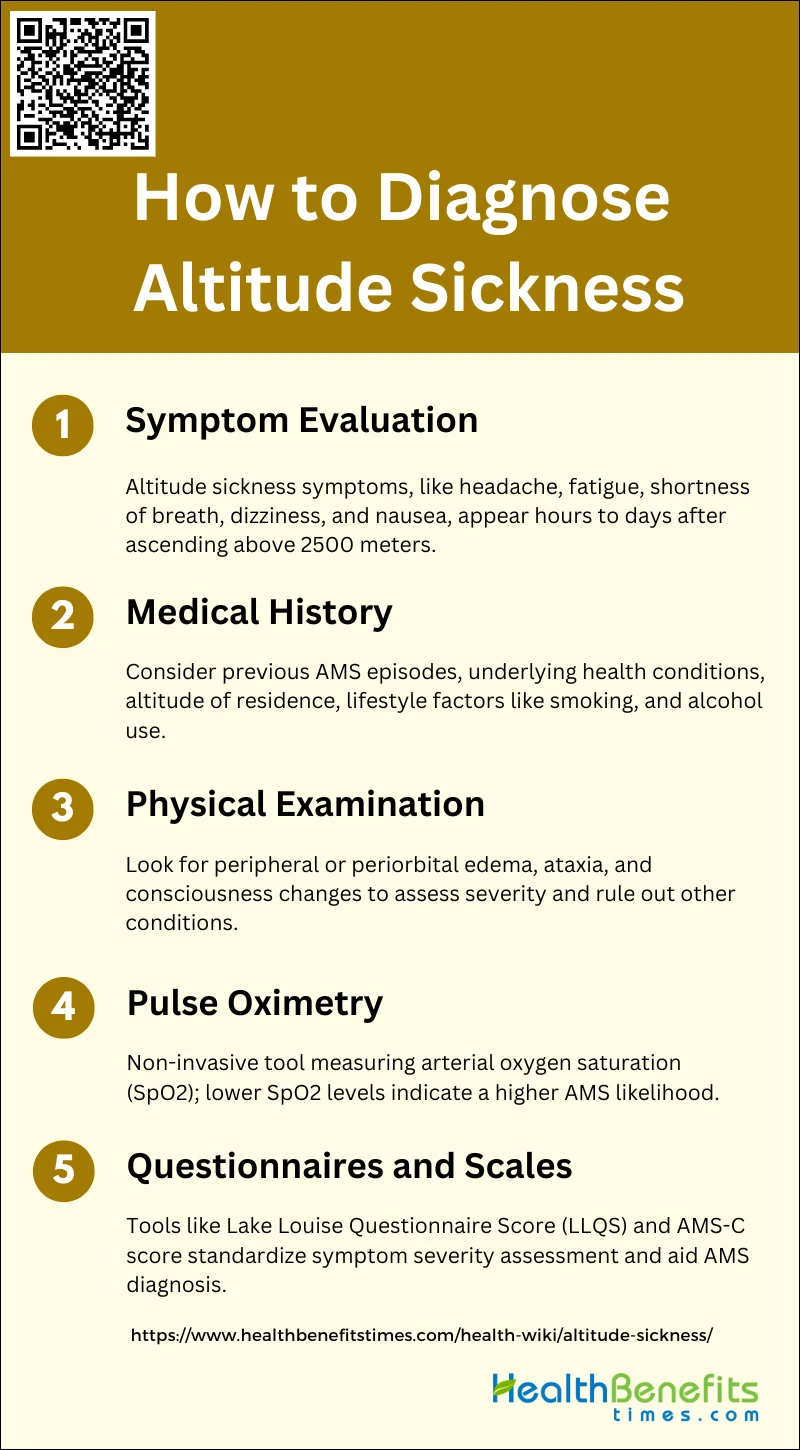

How to diagnose altitude sickness?

Diagnosing altitude sickness involves recognizing the symptoms and understanding the context of recent altitude exposure. Common symptoms include headache, nausea, dizziness, and fatigue, which typically appear within hours of ascending to high altitudes. To confirm a diagnosis, consider the following steps:

1. Symptom Evaluation

Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness (AMS), is characterized by a range of symptoms including headache, fatigue, shortness of breath, dizziness, nausea, and sleep disturbances. These symptoms typically manifest within hours to days after rapid ascent to high altitudes, usually above 2500 meters. The presence of three or more of these symptoms in the context of recent altitude exposure is often used to diagnose AMS. Headache is the most common symptom, while vomiting is less frequently reported. Symptom evaluation is crucial as it helps in early identification and management of AMS to prevent progression to more severe conditions like high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) or high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE).

2. Medical History

A thorough medical history is essential in diagnosing altitude sickness. Factors such as previous episodes of AMS, underlying health conditions (e.g., lung disease, heart conditions, diabetes), and the altitude of permanent residence can influence susceptibility to AMS. Individuals with a history of AMS or those residing at lower altitudes are at higher risk. Additionally, lifestyle factors such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical fitness levels should be considered, as they can impact the likelihood of developing AMS. Understanding these risk factors helps in identifying individuals who may require preventive measures or closer monitoring during altitude exposure.

3. Physical Examination

Physical examination plays a supportive role in diagnosing altitude sickness. Key signs to look for include peripheral or periorbital edema, ataxia, and changes in consciousness, which may indicate progression to HACE. While physical examination alone may not be sufficient for a definitive diagnosis, it helps in assessing the severity of symptoms and ruling out other conditions that may present similarly. For instance, a structured interview and short physical examination by an experienced investigator can provide valuable insights into the patient’s condition and aid in the accurate diagnosis of AMS5.

4. Pulse Oximetry

Pulse oximetry is a non-invasive tool used to measure arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) and can be helpful in diagnosing AMS. Studies have shown that lower SpO2 levels are associated with a higher likelihood of developing AMS. However, the utility of pulse oximetry in diagnosing AMS is debated, as some studies have not found a significant association between SpO2 levels and AMS. Despite this, monitoring SpO2, especially during the initial hours of altitude exposure, can provide useful information about the individual’s acclimatization status and help predict the risk of developing moderate-to-severe AMS.

5. Questionnaires and Scales

Questionnaires and scales, such as the Lake Louise Questionnaire Score (LLQS) and the Acute Mountain Sickness-Cerebral (AMS-C) score, are widely used for diagnosing AMS. These self-reported tools assess the severity of symptoms and provide a standardized method for diagnosing AMS. The LLQS, for example, evaluates symptoms like headache, gastrointestinal distress, fatigue, and dizziness, with a score of 5 or greater indicating AMS. These tools are valuable in both clinical and research settings, allowing for consistent and reliable diagnosis of AMS across different populations and altitudes.

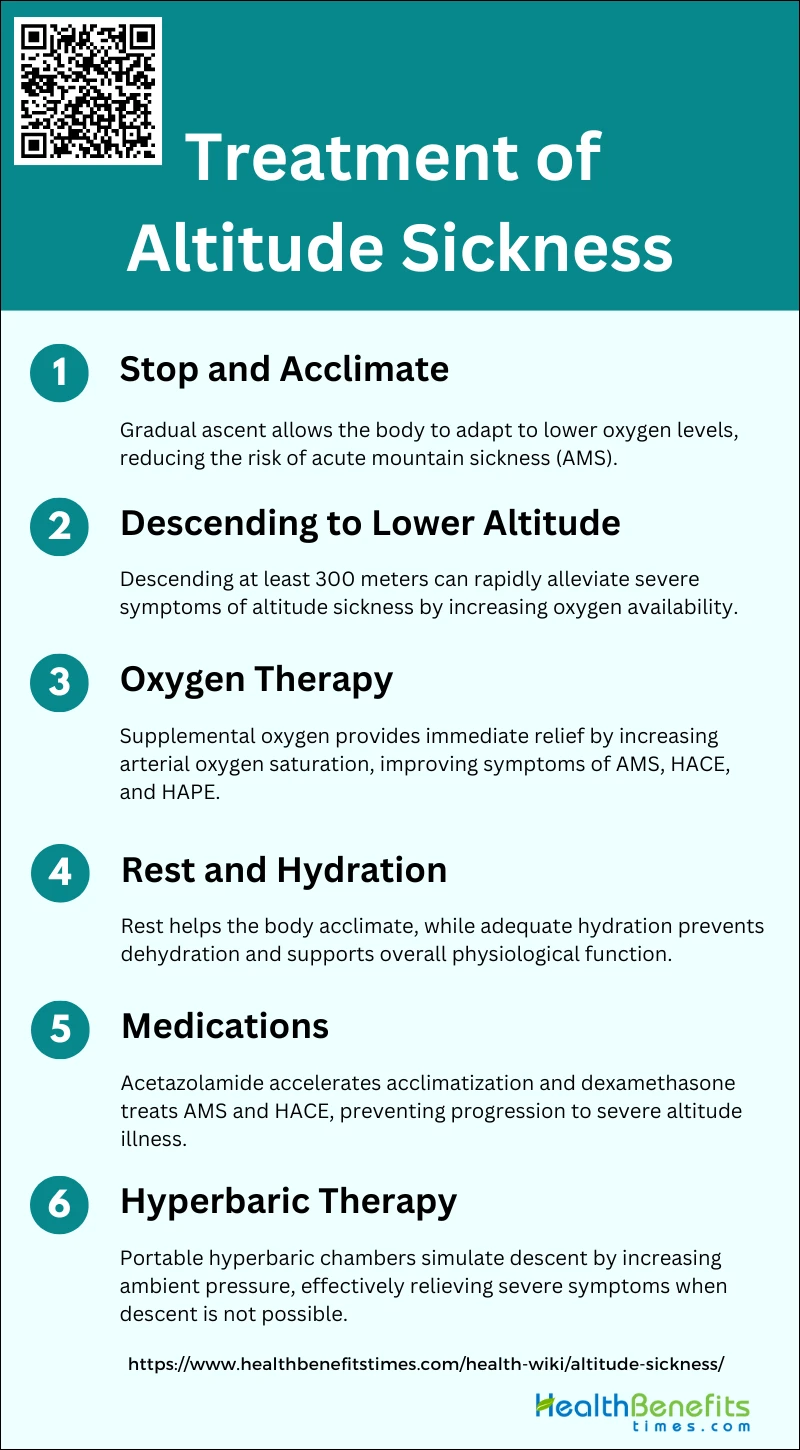

Treatment of Altitude Sickness

Effective treatment often involves descending to a lower altitude, taking medications, and ensuring proper hydration and rest. Below is the list of treatment of Altitude Sickness:

1. Stop and Acclimate

Stopping and allowing the body to acclimate is a fundamental strategy in preventing and managing altitude sickness. Gradual ascent is crucial as it allows the body to adapt to lower oxygen levels, reducing the risk of acute mountain sickness (AMS) and other altitude-related illnesses. Acclimatization involves physiological changes such as increased ventilation and heart rate, and a reduction in plasma volume to improve oxygen-carrying capacity. This process can significantly decrease the incidence of AMS, making it a key preventive measure.

2. Descending to Lower Altitude

Immediate descent to a lower altitude is the most effective treatment for severe altitude sickness, including high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE). Descending by at least 300 meters can rapidly alleviate symptoms by increasing oxygen availability and reducing hypoxic stress on the body. This approach is often recommended when symptoms are severe or do not improve with other treatments, as it directly addresses the underlying cause of altitude sickness.

3. Oxygen Therapy

Oxygen therapy is a widely used treatment for altitude sickness, providing immediate relief by increasing arterial oxygen saturation. Studies have shown that supplemental oxygen can significantly improve symptoms of AMS, HACE, and HAPE. Oxygen can be administered via facemask or nasal cannula, and its effectiveness is comparable to that of hyperbaric therapy in some cases. This treatment is particularly useful when descent is not immediately possible.

4. Rest and Hydration

Rest and hydration are essential supportive measures in managing altitude sickness. Physical exertion can exacerbate symptoms, so rest helps the body acclimate more effectively. Adequate hydration is crucial as dehydration can worsen symptoms and impede acclimatization. Maintaining fluid balance supports overall physiological function and can help mitigate the effects of altitude on the body.

5. Medications

Medications such as acetazolamide and dexamethasone are commonly used to prevent and treat altitude sickness. Acetazolamide helps by accelerating acclimatization, reducing the incidence and severity of AMS5. Dexamethasone is effective in treating AMS and HACE, particularly when rapid descent is not feasible. These medications can be critical in managing symptoms and preventing progression to more severe forms of altitude illness.

6. Hyperbaric Therapy

Hyperbaric therapy involves using a portable hyperbaric chamber to simulate descent by increasing ambient pressure, thereby enhancing oxygen availability. This method has been shown to be as effective as oxygen therapy in relieving symptoms of AMS. Hyperbaric chambers, such as the Gamow Bag, are particularly useful in remote settings where immediate descent is not possible, providing a practical alternative for managing severe altitude sickness.

Prevention of Altitude Sickness

Preventing altitude sickness involves taking proactive measures to help the body acclimatize to higher elevations. Gradual ascent, staying hydrated, and avoiding alcohol are crucial steps in reducing the risk. Effective prevention strategies include:

1. Gradual Ascent

Gradual ascent is the most reliable and safest method to prevent high altitude illness (HAI). Allowing the body sufficient time to adjust to moderate hypoxia through a process called acclimatization is crucial. This method improves sleep, increases comfort, and enhances overall well-being at high altitudes. It is recommended to ascend slowly, allowing the body to adapt to the reduced oxygen levels, which significantly reduces the risk of developing altitude sickness.

2. Take Rest Days to Acclimate

Taking rest days during ascent is essential for acclimatization. These rest periods allow the body to adjust to the lower oxygen levels encountered at higher altitudes. By incorporating rest days, individuals can reduce the risk of acute mountain sickness (AMS) and other altitude-related illnesses. This approach is particularly important when ascending to altitudes above 2,500 meters, where the risk of AMS increases significantly.

3. Sleep at a Lower Altitude if Possible

Sleeping at a lower altitude than the highest point reached during the day can help in preventing altitude sickness. This practice, known as “climb high, sleep low,” allows the body to recover in an environment with relatively higher oxygen levels, thereby reducing the risk of developing AMS. This strategy is effective in promoting acclimatization and minimizing the symptoms associated with altitude sickness.

4. Adequate Hydration

Maintaining adequate hydration is crucial in preventing altitude sickness. Dehydration can exacerbate the symptoms of AMS, such as headaches and dizziness. Drinking plenty of fluids helps to maintain blood volume and circulation, which is essential for oxygen delivery to tissues. It is recommended to avoid caffeinated and alcoholic beverages as they can contribute to dehydration.

5. Medications for Prevention

Medications such as acetazolamide and dexamethasone are commonly used for the prevention of AMS. Acetazolamide helps to acclimatize by increasing ventilation and improving oxygenation, while dexamethasone is effective in reducing inflammation and preventing severe AMS. These medications are particularly useful for individuals who need to ascend rapidly or have a history of altitude sickness.

6. Avoid Alcohol and Sleeping Pills

Avoiding alcohol and sleeping pills is important when ascending to high altitudes. Both substances can depress the respiratory system, leading to decreased oxygen levels in the blood. This can exacerbate the symptoms of AMS and hinder the acclimatization process. It is advisable to refrain from consuming alcohol and using sleeping pills to ensure optimal respiratory function and oxygenation.

7. Eat Carbohydrates

Consuming a diet rich in carbohydrates can help in preventing altitude sickness. Carbohydrates require less oxygen for metabolism compared to fats and proteins, making them a more efficient energy source at high altitudes. Eating carbohydrate-rich foods can help maintain energy levels and reduce the risk of developing AMS. It is recommended to include foods such as bread, pasta, and fruits in the diet while ascending to high altitudes.