Aging is a complex process characterized by a gradual decrease in the body’s ability to adapt to the environment and the accumulation of changes over time. It involves a deterioration of physiological functions necessary for survival and fertility. Aging affects not only the biological aspects of an organism but also its psychological and social dimensions. It is associated with various hallmarks, including genomic instability, epigenetic alterations, mitochondrial dysfunction, and cellular senescence. Aging is a risk factor for many chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and neurological disorders. The causes of aging are still unknown, but theories suggest that it may be due to the accumulation of damage or programmed internal processes. Understanding the mechanisms of aging and its impact on human development is crucial for developing interventions to delay or prevent age-related diseases.

Difference between chronological and biological age

Chronological age is defined as a person’s age based on the passage of time, while biological age is a measure of the aging process based on physiological variables. Biological age is considered a more accurate indicator of aging as it considers genetic and environmental factors that can impact the aging process. Various methods, such as multiple linear regression, principal component analysis, and deep learning methods, are used to quantify biological age. The “age gap,” or the difference between biological and chronological age, is viewed as a complementary indicator of aging that can provide additional information beyond chronological age alone. Biological age estimation relies on biomarkers and statistical models, and future research aims to identify new markers and methods for constructing biological age models. Understanding the distinction between chronological and biological age is crucial for evaluating the aging process and developing interventions for healthy aging.

Types of Aging

1. Biological Aging

Biological aging refers to the process of aging at the biological level, which involves the interplay of age, chronic disease, lifestyle, and genetic risk. It can be evaluated using longitudinal organ imaging and physiological phenotypes. Various organ systems, including cardiovascular, pulmonary, musculoskeletal, immune, renal, hepatic, metabolic, gray matter, white matter, and brain connectivity, contribute to an individual’s overall biological age. Mechanisms such as genetic damage accumulation, genomic instability, and DNA damage and repair imbalance are involved in biological aging. Various markers and methods, including supervised machine learning algorithms, have been developed to estimate biological age and investigate its relationship with mortality risk, genetics, and epigenetics. Traditional approaches and deep learning methods have been utilized to create biological age models based on selected aging biomarkers. Examining DNA methylation and age-related lesions can offer insights into the pathological basis of biological age.

2. Chronological Aging

Chronological aging is the natural process of aging that occurs in all individuals over time. It is a result of the passage of time and is not influenced by external factors such as sun exposure. Chronological aging is characterized by changes in the skin, including thinning, fine wrinkles, loss of elasticity, and xerosis. These changes are more common in females than males. The molecular pathways involved in chronological aging are similar to those involved in photoaging, which is aging caused by sun exposure. However, the extent of sun exposure and skin pigment play a larger role in photoaging. Understanding the mechanisms of chronological aging is crucial for the development of anti-aging therapies. Treatment with retinoids has been shown to inhibit collagen degradation and promote collagen synthesis, leading to improvements in the appearance of chronologically-aged skin.

3. Cosmetic Aging

Cosmetic aging refers to the changes in skin appearance that occur as a result of the aging process. It is influenced by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic aging is the natural process of chronological aging, which leads to alterations in the skin such as dryness, loss of skin laxity, and the development of fine wrinkles. Extrinsic aging, on the other hand, is caused by external factors such as exposure to UV radiation, smoking, and environmental stressors. It is characterized by the development of fine and coarse wrinkles, roughness, dryness, and pigmentary changes. The use of anti-aging cosmetic products and aesthetic treatments can help address the signs of cosmetic aging. Facial-firming cosmetics, in particular, have been found to positively correlate with self-esteem in women. Additionally, non-ablative skin resurfacing methods, such as photo rejuvenation, have been developed to stimulate collagen production and improve the appearance of photoaged skin.

4. Social Aging

Social aging refers to the changes in social behavior and relationships that occur as individuals age. It is an important aspect of the aging process as social interactions play a crucial role in the well-being and survival of group-living organisms. Various factors contribute to social aging, including senescence, adaptations to mitigate the negative effects of aging, and positive effects of age and demographic changes. In modern postindustrial societies, the importance of different types of social practices, such as family, work, and leisure, changes with age. The relationship between these practices can overlap, complement, or substitute each other, leading to different life strategies for older individuals. Social gerontology, the sociological-anthropological component of gerontology, is concerned with studying the sociocultural aspects of aging and the place of the elderly in social structures. Understanding social aging is crucial for developing a holistic understanding of the aging process and its impact on individuals and society.

5. Psychological Aging

Psychological aging refers to the changes in cognition, personality, emotions, coping, and control that occur as individuals grow older. It is influenced by both normal and abnormal changes in mental health and cognitive function, as well as adaptive psychological mechanisms to counteract age-related losses. Cognitive changes in aging include age-related changes in cognitive performance, cognitive plasticity, and cognitive reserve. Emotional self-regulation and the positivity effect are also important aspects of psychological aging. Additionally, behavioral regulation in later life involves successful adaptation to age-related losses through selective optimization with compensation. Psychological aging can have a significant impact on the everyday life of older individuals, and strategies such as mental and physical exercise, challenging negative stereotypes about aging, and preventive measures can help prevent premature functional decline. Overall, understanding psychological aging is crucial for providing effective interventions and promoting healthy aging.

6. Economic Aging

Different types of aging can be classified based on their economic consequences. The study of the economics of aging is a subject of interest in many developed countries due to the projected significant increase in the population over the age of sixty-five in the coming decades. The economic effects of population aging vary from country to country, influenced by factors such as declining fertility rates, the consumption patterns of older individuals, and the availability of support systems for the elderly. Various countries are at different stages of population aging, with Japan considered a super-aging society, the United States in the early stages of an aging society, and China and South Korea just beginning to experience population aging. It is essential for policymakers to understand the economic implications of aging in order to address challenges such as sustaining public pension and healthcare programs, promoting economic growth, and balancing expenditures on education and other programs for children.

7. Spiritual Aging

Spiritual aging is a significant aspect of the aging process that has been increasingly recognized in recent years. It involves the exploration and cultivation of spirituality in older adults, which can positively impact their overall well-being. Studies have demonstrated that spirituality can provide a sense of purpose, meaning, and connection with others, helping older adults to cope with physical, mental, and social challenges. As individuals age, there is a noticeable increase in spiritual growth and a deepening sense of soulful aging, alongside a greater vulnerability to frailty and awareness of mortality. Engaging in spiritual and religious practices has been linked to improved health outcomes and can act as a protective factor against the development of geriatric conditions such as depression, disability, and frailty. Recognizing the importance of spirituality in later life is essential in the context of longer lifespans, and further research in this area can enhance our understanding and support the spiritual well-being of older adults.

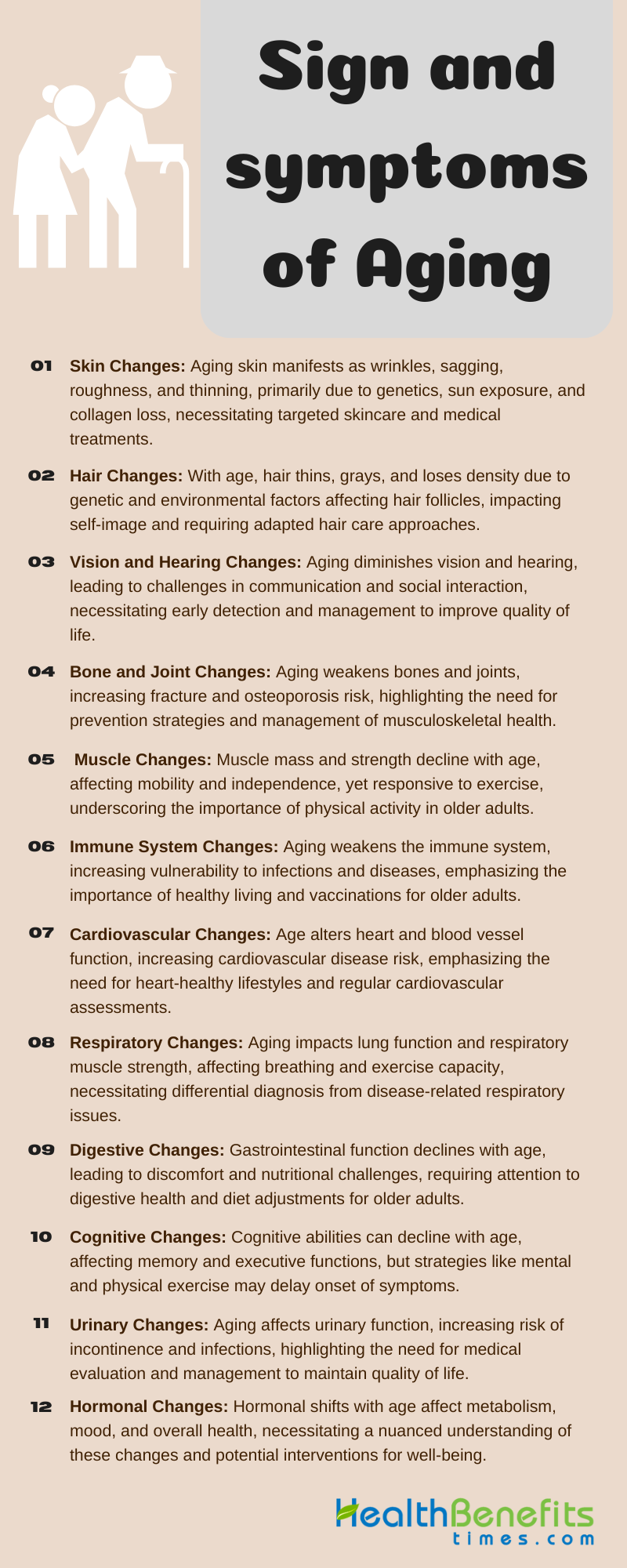

Sign and symptoms of Aging

Aging is a natural process that affects everyone and is characterized by various signs and symptoms. Some of the most common signs and symptoms of aging include:

1. Skin changes:

The signs and symptoms of aging skin include wrinkling, loss of elasticity, laxity, rough-textured appearance, and thinning of the epidermis. These skin changes are caused by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors, such as genetic influences, hormonal changes, and repetitive exposure to sunlight. Aging skin also experiences a reduction in the amount of collagen and elastin, leading to decreased skin strength and stability. In addition, aging skin is more prone to infections, wound healing disorders, inflammatory diseases, tumors, and associated paraneoplastic syndromes. The structural and functional alterations in aging skin can result in a variety of dermatoses and require specific recommendations for skin protection and the use of medications. Overall, the signs and symptoms of aging skin are a result of complex biological and environmental factors, and addressing these changes requires a comprehensive approach to skincare and medical interventions.

2. Hair changes:

Hair changes are a common indicator of aging. As individuals age, there are several noticeable alterations in hair. These changes encompass a decrease in hair thickness, reduced hair density, and the onset of androgenic alopecia. Graying of hair is also a notable change that occurs with aging. Furthermore, the luster and fullness of youthful hair may transition to thin, lackluster, and fragile hair commonly associated with aging. These changes are influenced by genetic and environmental factors that affect the cells of the hair follicle, including hair follicle stem cells and melanocytes. The aging process also results in structural changes to the hair fiber, a decline in melanin production, and an extension of the telogen phase of the hair growth cycle. These age-related alterations in hair can significantly impact self-perception, confidence, and overall appearance.

3. Vision and hearing changes:

Signs and symptoms of age-related changes in vision and hearing include a decline in sensory function, such as reduced visual acuity and hearing loss. Vision changes may present as redness, pain, irritation, excessive tearing, and decreased eyesight. Hearing changes, known as presbycusis, can lead to difficulty hearing and understanding speech, resulting in isolation, depression, and poorer social relationships. Age-related changes in the auditory and visual systems, including structural and functional changes in sensory receptors, cochlear and retinal ganglion neurons, and mitochondrial dysfunction, contribute to these impairments. It is crucial to assess vision and hearing ability during clinical examinations to identify impairments and provide appropriate treatment and aids to improve well-being, independent living, and reduce healthcare utilization and costs. Early detection and management of sensory system disorders can also help in the early diagnosis and delay the clinical manifestation of neurodegenerative diseases.

4. Bone and joint changes:

Aging results in progressive alterations in the musculoskeletal system, particularly in the bone and joint structures. These alterations can lead to various clinical issues, including fragility fractures, joint degeneration, and injuries to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Fragility fractures become more prevalent as individuals experience decreased bone mass and muscle mass, resulting in weakness and an increased risk of falls. Age-related osteoporosis is a complex condition characterized by changes in bone structure and metabolism, leading to a gradual loss of bone over time. Joint disorders are common among middle-aged and older adults, affecting all joint structures and causing significant healthcare challenges. Osteoarthritic changes, such as bone loss, joint space narrowing, subchondral bone sclerosis, and osteophyte formation, are frequently observed in X-ray images of aging individuals. These symptoms and changes underscore the impact of aging on the bone and joint health of individuals.

5. Muscle changes:

Aging results in progressive declines in muscle performance, with more significant changes occurring in the lower body compared to the upper body. Both muscle mass and power are impacted by aging, particularly affecting Type II muscle fibers. Sarcopenia, characterized by excessive muscle loss, is a consequence of the aging process. Aging also influences satellite cells and the response to exercise and muscle fiber injury. However, aging muscles do exhibit positive responses to exercise, even in very elderly individuals. The decline in muscle function associated with aging is due to structural and functional adaptations at both central and peripheral levels. Neural changes, such as degeneration of the human cortex and spinal circuitry function, play a crucial role in the deterioration of muscle quality and impairments in voluntary activation and motor performance. The aging process is linked to the loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, resulting from fiber atrophy, decreased regeneration capacity, mitochondrial dysfunction, and a reduced number of spinal cord motor neurons. Aging leads to changes in the coordination between behavioral and muscular levels, affecting coordination processes across behavior and muscle. Muscle weakness in older adults contributes to functional limitations, increased risk of falls, and adverse physiological changes. Resistance training can enhance muscle size and quality, even at low intensities, in older individuals.

6. Cardiovascular changes:

Aging is associated with a variety of changes in the cardiovascular system that affect both structure and function. These changes include cardiac hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, myocardial fibrosis, arterial stiffness, and endothelial dysfunction. Vascular structure and function are also impacted, with a decrease in vascular structure and alterations in vascular function. Additionally, there is an increase in cardiac fibrous tissue and a decrease in ventricular wall and myocardial contraction function. These changes can ultimately lead to impaired cardiovascular fitness in the elderly. Furthermore, aging is linked to a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis, heart failure, and diseases affecting other vital organs. Symptoms of cardiovascular diseases in older patients may be atypical, and responses to medications may differ compared to middle-aged individuals. Overall, the aging process has significant effects on the cardiovascular system, resulting in various structural and functional changes that can impact cardiovascular health in the elderly.

7. Respiratory changes:

Normal physiological and structural changes occur in the respiratory system as individuals age. These changes include alterations in the structure of the thoracic cage and lung parenchyma, abnormalities in lung function test results, ventilation and gas exchange issues, decreased exercise capacity, and reduced strength of respiratory muscles. The rib cage becomes stiffer, respiratory muscles weaken, and distal bronchioles exhibit a reduced diameter and tendency to collapse. Lung function, as assessed by forced expiratory volume and forced vital capacity, declines with age, while total lung capacity remains constant. Gas exchange is altered, with a gradual decrease in PaO(2) and a reduced capacity for carbon monoxide diffusion. Ventilatory responses to hypercapnia, hypoxia, and exercise diminish in elderly individuals. Changes in the airways contribute to an increased susceptibility to infections, higher residual volume and functional capacity, and decreased vital capacity. It is crucial to differentiate these respiratory changes from those caused by diseases in the elderly population.

8. Digestive changes:

Aging is associated with a variety of changes in the digestive system that can result in symptoms and disorders. These changes include a decrease in gastrointestinal (GI) motor functions, such as esophageal reflux, dysphagia, constipation, fecal incontinence, reduced compliance, and accommodation. Older individuals may also experience a reduction in peristaltic pressures, an increase in non-propulsive contractions, delayed transit time, and alterations in stool water content. Age-related modifications in sensory perceptions, salivation, oral health, nutrient absorption, and lactose tolerance may also occur. The prevalence of GI disorders in older adults is significant, with common complaints including swallowing disorders, reflux disease, constipation, peptic ulcer disease, and GI cancers. These changes in the digestive system can have a negative impact on quality of life and increase the risk of other diseases in the elderly population. Therefore, it is crucial to understand and address these age-related digestive changes in order to promote healthy aging and improve the overall well-being of older individuals.

9. Urinary changes:

Urinary changes are common symptoms of aging. Studies have shown that lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) can vary in severity throughout the year, with symptoms worsening in winter and improving in summer. Adiposity, or excess body fat, has been found to increase the risk of LUTS in men, but changes in adiposity over time do not appear to be associated with changes in LUTS severity. As individuals age, urinary function can deteriorate, leading to an increase in LUTS severity, prostate volume, and residual urine. In older adults, urinary incontinence can be a nonspecific sign of underlying health issues, such as infection or medication interactions. These urinary changes in aging individuals can contribute to a decline in quality of life and may require medical management.

10. Cognitive changes:

Cognitive changes are a common feature of aging, with declines in certain cognitive functions being the most significant. These changes include declines in speed of processing, working memory, and executive cognitive function. Age-related cognitive impairment can occur in various domains such as attention, perception, reasoning, decision making, execution, speech, and language. The impairment is influenced by the vulnerability of different brain regions and their associated dysfunctions with advancing age. However, it is important to note that cognitive decline in healthy individuals seems to occur later in life than indicated by cross-sectional studies, and intellectual functioning may decline rather late in life, if ever. Age-related diseases can accelerate cognitive decline, leading to impairments in everyday functional abilities. Strategies such as maintaining a healthy lifestyle, engaging in proper exercise, and creating an enriched environment may help delay the onset of cognitive symptoms in the setting of age-associated diseases.

11. Immune system changes:

Aging is associated with changes in the immune system, a phenomenon known as immunosenescence. These changes can result in a decrease in both the number and function of T cells, which play a crucial role in immune responses. Additionally, there are observed alterations in B cell functions, including reduced antibody production and response. The aging immune system also experiences dysregulation of inflammatory processes, leading to a chronic low-grade inflammation referred to as “inflammaging.” These age-related immune changes can lead to a decreased ability to combat infections, reduced response to vaccination, increased incidence of cancer, and a higher prevalence of autoimmune diseases. The involution of the thymus, responsible for producing new T cells, is one of the most significant changes in the aging immune system. Overall, immunosenescence is a complex process involving multiple alterations in immune cell function and phenotype, which can contribute to the signs and symptoms of aging in the immune system.

12. Hormonal changes:

Aging is characterized by hormonal changes that manifest in various signs and symptoms. These changes involve shifts in hormone secretion patterns, disruptions in feedback-feedforward networks, decreased tissue sensitivity to hormones, and diminished hormone bioavailability. Certain hormones, including melatonin, growth hormone, sex hormones, and dehydroepiandrosterone, decline with age, while others like TSH and cortisol may increase. These hormonal changes can result in decreased bone and muscle mass, reduced physical strength and vitality, increased visceral fat, and insulin resistance. Furthermore, age-related hormonal alterations can lead to lowered protein synthesis, body mass, and bone density, heightened risk for cardiovascular diseases, fatigue, depression, and decreased libido. It is important to recognize that distinguishing the effects of aging-related hormonal changes from the effects of aging itself can be challenging, and the efficacy of hormone replacement therapies in older individuals is still under investigation.

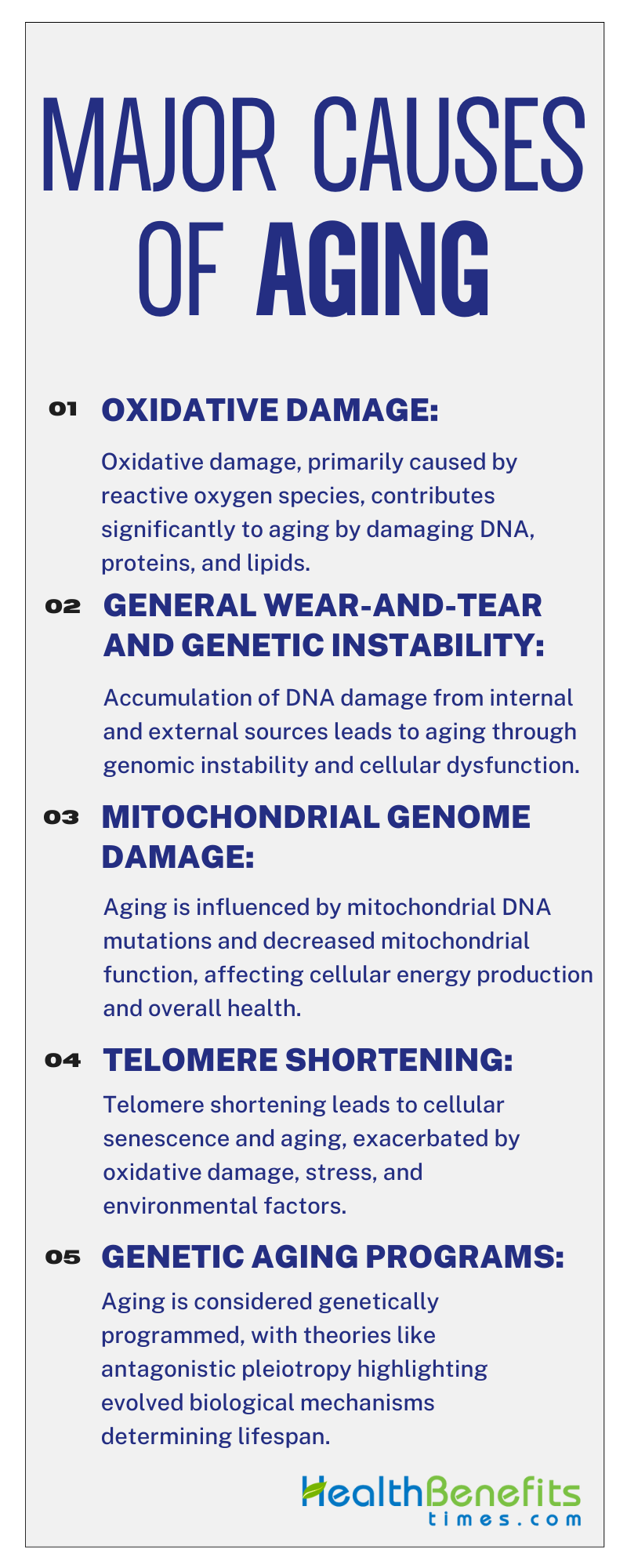

Major causes of Aging

Aging is a result of a combination of factors, including cellular damage, impaired maintenance mechanisms, and the tradeoff between reproduction and cellular preservation. The accumulation of damage in DNA, proteins, membranes, and organelles, as well as the formation of high molecular weight insoluble aggregates, contribute to the aging process. The failure to maintain a steady-state level of damage is due to limited resources allocated to preserving the integrity of the body. Different theories propose various cellular causes of aging, such as somatic mutations, free radicals, DNA damage, telomere attrition, and impairment of autophagy. Additionally, the efficiency of maintenance mechanisms plays a role in determining the lifespan of different mammalian species, with longer-lived species exhibiting more effective maintenance. The inverse relationship between reproductive potential and longevity suggests that available metabolic resources are shared between reproduction and preservation of the adult body. Overall, the causes of aging involve a complex interplay between cellular damage, maintenance mechanisms, and resource allocation.

1. Oxidative damage

Oxidative damage is a significant factor in the mechanisms of aging, as demonstrated in numerous research studies. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are primary contributors to this process, leading to the accumulation of damage in DNA, proteins, and lipids. The imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant defense systems results in oxidative stress, which accelerates the aging process. The oxidative stress theory of aging emphasizes the harmful effects of ROS on cellular functions and integrity over time, contributing to age-related functional decline. The impact of ROS-induced DNA damage, deficiencies in DNA repair pathways, and subsequent mutagenesis and epigenetic alterations further worsen the aging process, highlighting the complex relationship between oxidative damage and aging phenotypes. Ultimately, understanding and addressing oxidative damage are essential for uncovering the mechanisms underlying aging processes.

2. General wear-and-tear and genetic instability

Aging is a complex process influenced by various factors, including general wear-and-tear and genetic instability. The accumulation of DNA damage, both from internal and external sources, plays a significant role in aging. External sources such as ionizing radiation and chemicals, as well as internal factors like alkylation and hydrolysis, can lead to genomic instability, chromosomal aberrations, and mutations, ultimately causing cellular dysfunction. The theory of DNA damage accumulation in aging suggests that unrepaired DNA damage can result in genomic instability, affecting gene expression and leading to functional decline in tissues, which are characteristic of aging. The decline in DNA repair pathways with age allows for more frequent DNA lesions, contributing to the loss of genome integrity in somatic cells over time. Therefore, understanding and addressing these mechanisms are essential for uncovering the causes of aging.

3. Mitochondrial genome damage

Damage to the mitochondrial genome is a significant factor in the aging process. Mitochondria are essential for energy production and cellular activities, but they are susceptible to oxidative stress, which can cause damage to macromolecules within these organelles, particularly affecting mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). As individuals age, mitochondrial function decreases due to the accumulation of mtDNA mutations, a decrease in mtDNA copy number, and reduced oxidative capacity. Recent research suggests that mtDNA mutations primarily result from errors in replication rather than oxidative damage, with mtDNA polymerase γ (POLG) playing a role in mutagenesis. Environmental factors such as pollutants, pharmaceuticals, and ultraviolet radiation can worsen mtDNA damage, potentially speeding up the rate of mtDNA mutations and contributing to age-related diseases. In summary, damage to the mitochondrial genome is a key factor in the aging process, affecting cellular function and overall health.

4. Telomere shortening

Telomere shortening is a key factor in the aging process. Telomeres, which are protective caps at the ends of chromosomes, gradually shorten as cells divide due to limitations in DNA replication and suppression of telomerase in somatic cells. This shortening eventually leads to cells reaching a point of senescence, limiting their ability to divide further. Factors such as oxidative damage, replicative stress, genetics, epigenetics, and the environment can exacerbate this process. When telomeres become critically short, abnormal structures and genomic instability can form, leading to aging and age-related diseases in humans. Understanding the mechanisms of telomere shortening and its effects is crucial for identifying new molecular targets for diagnosing and treating age-related diseases.

5. Genetic aging programs

Aging is increasingly recognized as genetically programmed with mechanisms such as antagonistic pleiotropy (AP) contributing to the process of senescence. This programmed aging concept challenges the traditional view of aging as solely resulting from the accumulation of damages. The idea of programmed aging has gained traction in evolutionary biology and gerontology, suggesting that aging is purposefully caused by evolved biological mechanisms to confer evolutionary advantages. This shift in perspective highlights the importance of understanding the genetic control of aging, emphasizing the role of longevity genes and the regulation of bioenergetics in determining lifespan. The presence of genetically controlled specific mechanisms that determine aging supports the notion that aging is selectively advantageous and regulated by genes.

Factors influencing healthy ageing

Factors that influence healthy aging include a variety of elements that are essential for promoting well-being in the elderly population. Research emphasizes the importance of genetic and environmental factors in promoting longevity, as evidenced by the high number of centenarians in Bama, China, surpassing international standards. Successful aging is closely associated with factors such as marital status, family support, income levels, health perception, and cognitive abilities, underscoring the significance of individual circumstances in positive aging experiences. Additionally, healthy aging is closely connected to lifestyle choices, such as maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in physical activity, prioritizing mental well-being, participating in social activities, attending regular health check-ups, and implementing fall prevention strategies, all of which contribute to preserving functional ability and intrinsic capacity in older adults. Understanding and addressing these various factors are crucial for promoting healthy aging and improving the quality of life for the elderly population.

1. Individual Factors

Individual factors play a significant role in influencing healthy aging. Research has shown that personal characteristics, individual behaviors, and lifestyle choices have a substantial impact on healthy life expectancy (HLE). Factors such as abnormal waist-to-hip ratio, increased coffee consumption, reduced basal metabolic rate, elevated triglycerides, and C-reactive protein levels have been identified as detrimental to healthy aging, while moderate alcohol consumption has been recognized as a positive influence. Furthermore, a healthy lifestyle index that includes weight management, smoking cessation, physical activity, alcohol moderation, and a balanced diet has been linked to a higher likelihood of healthy aging, underscoring the importance of lifestyle choices in promoting overall health during aging. By focusing on individual factors such as lifestyle choices and personal characteristics, interventions can be customized to improve outcomes in healthy aging.

2. Environmental Factors

Environmental factors play a critical role in influencing healthy aging by affecting various aspects of aging-related diseases and longevity. Factors such as air quality, water pollution, and food contaminants have been identified as significant contributors to age-related diseases, posing a serious threat to the health of the elderly population. For example, exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) has been linked to the development of dementia, a common condition among the elderly. Furthermore, the presence of heavy metals in the environment, such as lead, mercury, and cadmium, has been linked to dyslipidemia in older adults, underscoring the harmful effects of chemical pollutants on health. Understanding the interactions between environmental factors and aging processes is crucial for developing preventive strategies at both individual and societal levels to promote healthy aging.

Techniques to Delay the Aging Process

1. Eat a healthy diet rich in whole grains, vegetables

Consuming a healthy diet that includes whole grains and vegetables is a key method to slow down the aging process. Research suggests that diets emphasizing fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, and nuts are associated with improved odds for healthy aging, reduced chronic disease risk, and increased longevity. Specifically, whole grains such as oats and barley have been shown to effectively lower cholesterol levels, while fruits and non-starchy vegetables like berries, citrus fruits, and green leafy vegetables are linked to improved cognitive performance and weight control. Additionally, a nutritionally balanced diet rich in vegetables and whole grains, along with probiotics, can beneficially modify the gut microbiota, potentially alleviating gastrointestinal symptoms and improving defecation habits. Therefore, incorporating whole grains and vegetables into one’s diet can play a significant role in promoting healthy aging and enhancing overall well-being.

2. Stop smoking

In order to slow down the aging process, it is crucial to stop smoking a cigarette smoke accelerates aging and significantly increases the risk of various diseases. Strategies for smoking cessation include pharmacological options such as nicotine replacement therapies, bupropion, and varenicline, which help reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings. Additionally, combining behavioral and cognitive counseling with pharmacotherapy can enhance smoking cessation rates. While many smokers are able to quit on their own, methods such as psychotherapy, nicotine chewing gum, clonidine, aversive behavior therapy, and hypnosis can assist those who are struggling to quit. Motivation is a key factor in successful smoking cessation, and combining psychotherapy with nicotine replacement therapy has shown promising results. Overall, quitting smoking not only increases life expectancy but also improves quality of life by reducing the biological damage caused by smoking.

3. Build physical and mental activities

Engaging in physical and mental activities is essential for slowing down the aging process. Research has shown that physical activity can help prevent cognitive decline in older adults, with exercise, light activity, and social participation all playing a significant role in maintaining cognitive function. Regular physical training and participation in sports can also help counteract the physiological changes that come with aging, leading to better mental health and potentially reducing the risk of depression and dementia in old age. Being physically active can improve cognitive efficiency and lower the risk of cognitive deficits and depression in older individuals, underscoring the importance of incorporating physical activity into clinical practice. Combining social activities with physical exercise can directly benefit cognitive functioning, as social engagement can improve mental health and increase physical activity, ultimately enhancing cognitive performance in older adults.

4. Maintain a healthy weight and body shape

Maintaining a healthy weight and body shape is essential for slowing down the aging process. Research indicates that individuals who maintain a youthful body shape as they age have a lower risk of lifestyle-related diseases commonly associated with aging. In addition, the administration of specific substances such as protein-homeostasis-influencing saccharide-based compounds, anti-amyloidogenic substances, and Krebs cycle metabolites can work together to impact aging processes and overall well-being. Body scanning techniques have been used to classify individuals into different body types, showing that aging results in distinct changes in body shape. Slim individuals tend to maintain their lean physique, while obese individuals remain in the same category. By combining these strategies with a healthy diet, regular exercise, and targeting specific antigens associated with aging, it is possible to collectively slow down the aging process and promote longevity.

5. Socialize

Socializing has been identified as a potential method to slow down aging by improving physical and mental health, as well as cognitive function. Social interactions are important for helping individuals deal with challenges in their social and environmental surroundings, which can significantly impact survival and reproductive success. Additionally, social aging, which involves changes in social behavior throughout life, can affect how individuals age and their overall well-being. Introducing socialization interventions, such as increasing social contact through technologies like web cameras, Skype, email, and phone, has shown promising results in enhancing social connections, communication time, and participant satisfaction among older adults. These interventions aim to address social isolation and promote social engagement in order to positively influence the aging process and overall health outcomes.

6. Get ample sleep

Obtaining sufficient sleep is essential in the effort to decelerate the aging process. Sleep plays a critical role in overall health, with inadequate sleep potentially leading to various health issues. Furthermore, proper sleep is crucial for cognitive function, metabolic regulation, and quality of life, particularly in older individuals. Maintaining healthy sleep patterns is not only beneficial for physical health but also for preventing age-related complications such as falls and injuries. Additionally, a synergistic approach involving substances that influence protein homeostasis, compounds that prevent amyloid formation, metabolites of the Krebs cycle, and other components can enhance the aging process and overall health. Recognizing the significance of sleep, as well as utilizing innovative methods such as administering specific compositions to influence protein homeostasis, can significantly contribute to slowing down the aging process and promoting longevity.

7. Reduce stress

Various methods can be employed to slow down the aging process and reduce stress based on research findings. One effective approach involves implementing a multimodal program for stress reduction, which includes health coaching, relaxation techniques, physical activity, and balneotherapeutic elements. Additionally, extracorporeal treatment of blood to target specific antigens associated with aging, such as mTOR, IGF-1, lipofuscin, and others, can help slow down the aging process. Furthermore, utilizing stress relief aging devices that combine thermal and vibration loading can effectively reduce welding residual stress in components, contributing to overall stress reduction and potentially slowing down the aging process. Complementary and alternative nursing management techniques like progressive muscle relaxation and deep breathing have also been shown to significantly reduce stress levels in elderly individuals, offering a non-pharmacological approach to stress reduction and potentially slowing down the aging process.

8. Build a strong social network

Building a strong social network is a crucial method to slow aging and promote healthy cognitive function. Research indicates that individuals with robust social connections have a lower risk of developing dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and vascular dementia. Moreover, studies have shown that a larger social network or higher levels of social engagement can significantly reduce the risk of cognitive decline and delay the progression of dementia. Social interactions and engagement have been linked to positive effects on cognitive function, even at the level of biomarkers, suggesting that maintaining strong social ties can have tangible benefits on brain health. Therefore, fostering and nurturing social relationships as part of a healthy lifestyle can be a powerful strategy to support healthy aging and overall well-being.

Health Risks commonly associated with Aging

1. Arthritis

Arthritis is a common and disabling health issue among the elderly population. Approximately 54.4 million US adults have been diagnosed with arthritis, with a significant number experiencing limitations in daily activities as a result. This has a substantial impact on quality of life and functional independence. Osteoarthritis, the leading cause of chronic disability in older adults, affects joints such as the hands, knees, hips, and spine, with knee osteoarthritis being a major source of pain and activity restriction. The management of arthritis in older individuals requires a multidisciplinary approach involving physical therapists, occupational therapists, physiatrists, orthopedic surgeons, and pain specialists to effectively control the disease. Addressing arthritis in the elderly involves not only relieving symptoms but also exploring interventions that can slow down or halt the structural progression of the disease, taking into account factors such as chronic inflammation and cellular changes associated with aging.

2. Heart Disease

Aging is closely linked to a higher prevalence of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as heart failure (HF), ischemic heart diseases, arrhythmias, and cardiomyopathies, which have a significant impact on older individuals, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. The aging population faces challenges in managing HF optimally, as elderly patients often have more comorbidities, lower adherence to guideline-directed medical treatment (GDMT), and lower rates of receiving recommended therapies like beta-blockers and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Additionally, age-related changes at the cellular and organ levels contribute to the development and progression of heart disease in the elderly, underscoring the importance of addressing geriatric conditions in HF treatment. Heart disease, including HF, remains a leading cause of mortality among the elderly, highlighting the critical need for tailored approaches to managing CVDs in aging populations.

3. Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a common health issue among the elderly population, characterized by reduced bone mass, structural deterioration, and increased susceptibility to fractures, particularly in the hip, wrist, and spine. The condition is influenced by factors such as hormonal changes, with decreases in estrogen for post-menopausal women and testosterone for older men playing significant roles. Osteoporotic fractures, often caused by low-energy trauma, place a significant burden on healthcare systems worldwide, resulting in disabilities and high treatment costs. Lifestyle changes, including adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, regular exercise, and avoidance of harmful habits like smoking and sedentary behavior, are important in reducing the risk of osteoporosis and associated fractures in older individuals. Efforts to promote preventive measures and raise awareness are crucial in effectively addressing this common age-related skeletal disorder.

4. Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a common neurodegenerative disorder associated with aging that affects a significant number of older adults worldwide. The development of AD involves a complex interaction of factors including oxidative stress, DNA methylation, histone modifications, and proteostasis. Redox imbalance, characterized by increased oxidative stress markers and impaired energy metabolism, is a key aspect of AD, along with the accumulation of amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylation of Tau proteins. Screening for cognitive impairment in older adults is essential, as AD is a major cause of cognitive decline and disability in the elderly. Modifiable risk factors such as lack of physical activity, cardiovascular health, and nutrition contribute to the development of AD, highlighting the importance of lifestyle changes for prevention. Addressing these risk factors and promoting healthy aging through improved diet, physical activity, and cognitive stimulation are crucial strategies for reducing the impact of AD on older populations.

5. Pneumonia

Pneumonia is a significant health concern among the elderly population, characterized by increased morbidity and mortality rates. Factors such as immunosenescence, comorbidities, malnutrition, and swallowing disorders contribute to the vulnerability of older individuals to pneumonia. The pathology of pneumonia is complex, with malnutrition and comorbidities being common geriatric syndromes that exacerbate the risk and prognosis of pneumonia in the elderly. Additionally, dysphagia plays a crucial role in pneumonia risk assessment, as it can lead to the aspiration of foreign material into the lungs, triggering pneumonia. Pneumonia Prevention strategies include lifestyle modifications, respiratory physiotherapy, and maintaining oral hygiene to reduce the risk of pneumonia in the elderly. Further research is needed to explore specific criteria for diagnosing aspiration pneumonia and to enhance management strategies for this vulnerable population.

6. Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus (DM) presents a significant health challenge in the elderly population, with a global prevalence of 123 million individuals over the age of 65 in 2017, a number that is expected to double by 2045. Elderly individuals with diabetes are at an increased risk of various geriatric syndromes, such as frailty, cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, falls, fractures, disability, and side effects related to polypharmacy, all of which can impact their quality of life and complicate the management of their diabetes. Managing type 2 diabetes in older adults requires personalized approaches that take into account factors such as glycemic targets and treatment options. While the ideal glycemic target is still a topic of debate, guidelines recommend tailored glycemic goals and antihyperglycemic treatments based on the individual’s medical history, comorbidities, and risk of hypoglycemia. Caregivers need to be vigilant for potential diabetes-related impairments in older adults, as the chronic effects of diabetes can resemble advanced symptoms of other conditions, necessitating thorough assessments to ensure appropriate care is provided.

7. Influenza

Influenza presents significant health challenges for aging populations, especially those aged 65 and older. Older adults are more vulnerable to severe complications of influenza due to age-related weakening of the immune system, chronic conditions, and reduced vaccine response. The impact of influenza in this demographic includes high rates of hospitalization, increased mortality, and substantial economic costs. Importantly, influenza can result in non-respiratory complications such as acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke, worsening functional decline and disability in frail older adults. Vaccination remains a critical preventive measure, although obstacles such as lower seroconversion rates and decreased vaccine effectiveness persist in older populations. It is recommended to enhance immunization strategies by using high-dose or adjuvanted formulations to improve protection against influenza in older adults.

8. Fall Injury

Fall injuries are a significant public health concern among the elderly population, with millions of cases reported annually worldwide. Factors contributing to fall risk include physiological, behavioral, and environmental changes, such as architectural barriers in the home environment. Chronic illnesses, sensory and memory problems, as well as specific injury characteristics like hip and head injuries, are associated with higher rates of emergency department visits and hospitalizations among older adults who experience fall injuries. Preventive measures are crucial, with physical activity, home safety, medication management, and vision care highlighted as critical steps in fall prevention. Multifactorial interventions, including disease management, podiatric care, visual correction, medication optimization, and home environment adaptations, are recommended to reduce fall risk and improve outcomes in high-risk individuals.

9. Oral health

Aging presents significant challenges to oral health, with various factors contributing to common health issues in older individuals. These may include tooth loss, dental cavities, gum diseases, and lesions in the mouth lining, which can affect their ability to perform oral functions effectively. Furthermore, older adults often experience degenerative changes that worsen with age, leading to prevalent oral diseases such as cavities and gum disease, which are linked to overall health problems. Medications taken by older individuals can reduce saliva production, further complicating oral health. These challenges not only impact physical well-being but also have emotional effects, causing discomfort, lower self-esteem, and affecting the enjoyment of eating. To address these issues, a comprehensive approach involving effective communication between healthcare providers is essential to prevent rapid deterioration of oral health in older individuals.

10. Depression

Depression is a common health issue among the elderly population, significantly impacting their well-being. Globally, approximately 15% of adults aged 60 and above experience a mental health disorder, with depression being a prevalent concern. Among the elderly, depression is the most common mental disorder, affecting around 12.3% of this demographic and increasing with declining health and disability. Women are more vulnerable to depression than men in older age groups, and depression in elderly men carries a higher risk of completed suicide. The clinical presentation of depression in the elderly varies with age, underscoring the importance of accurate diagnosis using tools such as the Geriatric Depression Scale. Treatment typically involves a combination of pharmacotherapy, psychoeducation, psychotherapy, and psycho-correction, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors like Escitalopram being a preferred choice due to their effectiveness and safety profile.

11. Shingles

Shingles, a prevalent health issue among the elderly, is caused by the reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, resulting in a painful rash. The frequency and severity of shingles increase with age, often leading to serious consequences such as post-herpetic neuralgia, visual impairments, and the need for hospitalization. Post-herpetic neuralgia, a common complication, can persist long after the rash disappears, significantly affecting quality of life. Vaccination, particularly with the new Zostavax vaccine, has shown effectiveness in preventing shingles in older adults, reducing the likelihood of complications and improving overall health outcomes. With the aging population expanding, addressing shingles and its complications is essential to enhance the well-being and quality of life of older individuals.

Tips for Healthy Ageing

In order to promote healthy aging, individuals should adopt a lifestyle that includes maintaining healthy eating habits, engaging in regular physical activity, managing weight effectively, enhancing mental well-being, participating in social activities, undergoing routine health check-ups, avoiding smoking, and taking preventive measures against falls. Additionally, healthy aging involves developing and sustaining functional abilities to ensure well-being in older age. As the global population ages, the importance of healthy aging is increasingly recognized as a crucial societal goal. Successful aging is seen as a process in which older individuals maintain their functionality within predetermined boundaries, emphasizing the significance of maintaining physical and mental capacities. By prioritizing these tips for healthy aging, individuals can enhance their quality of life and well-being as they age.