English ivy helps in reducing indoor air pollution and certain allergens from the house like molds and other fungus growth. Therefore its dual importance of improving the environment along with its beautiful ornamental looks makes this plant one of the most desirable indoor air purifying plants. It has been and continues to be widely sold in the U. S. as an ornamental plant. It has escaped gardens and naturalized in a large number of eastern, mid-western and pacific coast states. In some climates such as in the Pacific Northwest, it is considered by some to be an invasive invader of woodland and open areas where it often aggressively displaces native vegetation by densely smothering large areas of ground with its trailing densely-leaved stems or by climbing into tree canopies via clinging aerial rootlets.

Common Ivy Facts

| Common ivy Quick Facts | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Common ivy |

| Scientific Name: | Hedera helix |

| Origin | Northern Africa (i.e. Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia), the Azores, the Madeira Islands, the Canary Islands, all of Europe and western Asia (i.e. Cyprus, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and southern Russia). |

| Colors | Initially green turning to dull bluish-purple or black as it matures |

| Shapes | Berry (it is actually a drupe) 6–8 mm (0.2–0.3 in) in diameter |

| Flesh colors | Pruple |

| Taste | Bitter, pungent |

| Health benefits | Good for rheumatism, gout, whooping cough, bronchitis, skin eruptions, swollen tissue, painful joints, burns, gallbladder disorders, dysentery, neuralgia and neuralgia. |

| Name | Common ivy |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Hedera helix |

| Native | Northern Africa (i.e. Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia), the Azores, the Madeira Islands, the Canary Islands, all of Europe and western Asia (i.e. Cyprus, Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey, Armenia, Georgia and southern Russia). |

| Common Names | Ivy, English ivy, Algerian ivy, Baltic Ivy, Common Ivy, needlepoint ivy, ripple ivy, Algerian Ivy, Baltic Ivy, Branching Ivy, California Ivy, Glacier Ivy, Hahn’s Self Branching English Ivy, Sweetheart Ivy, bindwood and lovestone |

| Name in Other Languages | Afrikaans: Ivy, eishqat mutasaliqa (عشقة متسلقة) Albanian: Dredhkë, urthi Amharic: Ayivī (አይቪ) Arabic: Labilab (لبلاب) Armenian: baghegh (բաղեղ), baghegh sovorakan (բաղեղ սովորական) Azerbaijani: Ivy, Adi daşsarmaşığı Basque: Ivy, Huntz arrunt, untz, untza, untza-ostoa, xira Belarusian: Pliušč (плюшч), Pliušč zvyčajny (Плюшч звычайны) Bavarian: Eabam Bengali: Cirahariṯ latābiśēṣa (চিরহরিৎ লতাবিশেষ) Bosnian: Bršljan Bulgarian: Brŭshlyan (бръшлян), obiknoven brŭshlyan (обикновен бръшлян) Catalan: Heura, edra, elres, eura, gedra, hedra, hedrera, heurera, lleura Chichewa: Ivy Cebuano: Ivy Chinese: Cháng chūnténg (常春藤) Cornish: Idhyow Corsican: Edera Croatian: Bršljan Czech: Břečťan, břečťan popínavý Danish: Vedbend, Almindelig vedbend Dutch: Klimop English: English ivy, Ivy, European ivy, Italian ivy, common ivy Esperanto: Hedero, Helica hedero Estonian: Luuderohi, harilik luuderohi Filipino: Galamay-amo Finnish: Muratti, Varjomuratti, Euroopanmuratti, köynneliäs muratti French: Lierre, lierre grimpant, Bourreau des arbres, Herbe de St Jean, lierre, lierre commun, courroie de Sain-Jean, drienne, herbe de Saint-Jean, lierre des poètes, lierret, rondelette, rondette, rondote, terrette Frisian: Klimop Galician: Hera, Hedra Georgian: Ivy, chveulebrivi suro (ჩვეულებრივი სურო) German: Efeu, Gewöhnlicher Efeu, Baumefeu, Eibich, gemeiner Efeu Greek: Kissós (κισσός) Gujarati: Ā’ivi (આઇવિ) Haitian Creole: Ivy Hausa: Aiwi Hawaiian: Alalā Hebrew: Kisos hachoresh, קִיסוֹס, קיסוס החורש, קִיסוֹס הַחֹרֶשׁ Hindi: Aaivee lata (आइवी लता), lablab Hmong: Hmab Hungarian: Borostyán, közönséges borostyán Icelandic: Ivy, Bergflétta Igbo: Aiviri Indonesian: Ivy Irish: Ivy, eidhneán, Italian: Edera, ellera Japanese: Aibî, tsut (ツタ), Seiyoukidzuta (セイヨウキヅタ), seiyô-kizuta, Aibī (アイビー), Kidzuta (キヅタ) Javanese: Ivy Kabyle: Adafal Kannada: Hasiru (ಹಸಿರು) Kashubian: Efoj Kazakh: Sırmawıq (шырмауық) Khmer: Volli (វល្លិ) Kinyarwanda: Ivy Korean: Yeoja ileum (여자 이름), aibi (아이비) Kurdish (Kurmanji): Gîhagerînek Kyrgyz: Cırmook (чырмоок) Lao: Ivy Latin: Hedera Latvian: Efeja, Baltijas efeja, parastā efeja Limburgan: Wintjergreun Lithuanian: Gebenė, Gebenė lipikė, paprastoji gebenė Lower Sorbian: Wšedny blušć Luxembourgish: Ivy, Gewéinlecht Wantergréng Macedonian: Bršlen (бршлен) Malagasy: Ivy Malay: Ivy Malayalam: Vaḷḷippana (വള്ളിപ്പന) Maltese: Ivy Maori: Ivy Marathi: Vel (वेल) Mongolian: Mölkhöö urgamal (мөлхөө ургамал) Myanmar (Burmese): Tite kaut nwalpain (တိုက်ကပ်နွယ်ပင်) Neapolitan: Ellera Nepali: Ciraharita (चिरहरित) Netherlands: Klimop North Frisian: Efeu Norwegian: Eføy, Bergflette, bergflette Odia: Ivy Pashto: Ivy Persian: پیچک, عشقه Polish: Bluszcz, bluszcz pospolity, bluszcz pospolity, Portuguese: Hera, Hedera-variegata, aradeira, hedra, hera-comum, hera-dos-muros, heradeira, hereira, hédera Punjabi: Ā’īvī (ਆਈਵੀ) Romanian: Lederă, iederă Russian: Plyushch (плющ), Plyushch obyknovennyy (Плющ обыкновенный), plyushch bal’tiyskiy (плющ бальтийский) Sardinian: Edra Samoan: Ivy Scots Gaelic: Eidheann, Eidhinn, Gort Serbian: Brshljan (бршљан) Sesotho: Ivy Shona: Ivy Sindhi: آئي Sinhala: Ayivi (අයිවි) Slovak: Brečtan, brečtan popínavý Slovenian: Ivy, navadni bršljan Somali: Ivy Spanish: Hiedra, enredadera, yedra comun, Navadni bršljan, anzosto, aunzosto, cazuz, hedra, hiedra común, liedrera, yedra Sudanese: Ivy Swahili: Ivy Swedish: Murgröna, murgroena Tajik: Baxmali darozpat (бахмали дарозпат) Tamil: Aivi (ஐவி) Tatar: пычрак Telugu: Aivī (ఐవీ) Thai: Mị̂ leụ̄̂xy (ไม้เลื้อย) Turkish: Sarmaşık, Duvar sarmaşığı Turkmen: Pyçak Ukrainian: Plyushch (плющ), Plyushch zvychaynyy (Плющ звичайний) Upper Sorbian: Wšědny blušć Urdu: آئیوی Uyghur: Ivy Uzbek: Pechak Vietnamese: Cây bạch dương, Dây thường xuân Welsh: Eiddew, Iorwg Xhosa: Ivy Yiddish: Pliushsh (פּליושש) Yoruba: Ivy Zulu: Ivy |

| Plant Growth Habit | Fast-growing, low maintenance, evergreen, perennial, self-clinging climber or rambling groundcover |

| Growing Climates | Forests, forest edges, rocky places, forest floors, trees, rocky and shady places, waste places, riverbeds, stream banks, cliffs, woodlands, hedges, water courses, riparian areas, wetlands, closed forests, roadsides, gardens and fields. It is often found climbing over trees, posts, walls and fences |

| Soil | Does not thrive in wet or extremely moist areas, but will grow in a wide range of soil ph |

| Plant Size | 15 m (49ft) tall and 5 m (16ft) wide at a medium rate |

| Root | Roots are generally shallowly rooted, but robust. English ivy also forms aerial, clinging rootlets, allowing it to adhere and climb vertically |

| Stem | Long, either creeping or climbing and may attain a length of up to 30 m |

| Bark | Light brown slightly rough and finely scaly with numerous rootlets at the nodes |

| Twigs | Slender, light green but later turning light brown with aerial rootlets |

| Leaf | Alternately arranged along the stems and borne on stalks (i.e. petioles) 2.5-11 cm long. They vary from egg-shaped in outline (i.e. ovate) with entire or wavy margins to heart-shaped (i.e. cordate) or shallowly 3-5 lobed (i.e. palmately lobed). |

| Flowering season | September to November |

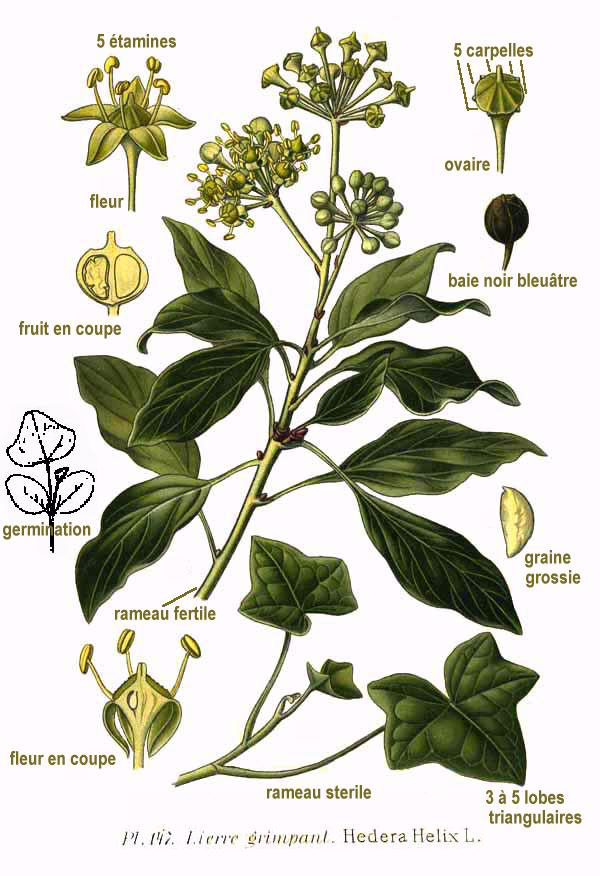

| Flower | The small flowers are arranged in clusters, with all of the flower stalks. Each flower has five yellowish-green petals that are 3-5 mm long, but no obvious sepals. They also have five stamens and five partially fused styles that are about 1.5 mm long. |

| Fruit Shape & Size | Berry (it is actually a drupe) 6–8 mm (0.2–0.3 in) in diameter |

| Fruit Color | Initially green turning to dull bluish-purple or black as it matures |

| Flesh Color | Purple |

| Seed | Fruit consists of 2-3 whitish seeds |

| Varieties |

|

| Propagation | By stem cutting or seeds |

| Flavor/Aroma | Aromatic and slightly resinous odor |

| Taste | Bitter, pungent |

| Plant Parts Used | Leaves, berries |

| Lifespan | Can be extremely long-lived and may reach an age of over 400 years |

| Season | November to January |

| Health Benefits |

|

Etymology

The genus name Hedera is the Classical Latin word for ‘ivy’, which is cognate with Greek χανδάνω (khandánō) ‘to get, grasp’, both deriving ultimately from Proto-Indo-European gʰed- ‘to seize, grasp, take’. The specific epithet helix is derived from Ancient Greek ἕλιξ (elix), ‘helix’, and from the Latin helicem, spiral, first used around 1600.The binomial in its entirety thus has the meaning “the clinging plant that coils in spirals (helices)”. The modern English ivy derives from Middle English ivy, from Old English īfiġ, deriving in turn from Proto-Germanic ibahs. The meaning is uncertain, but the word may be cognate with the Ancient Greek ἴφυον (íphuon), referring to not Hedera helix, but the unrelated English lavender, or Lavandula angustifolia.

Plant Description

Common ivy is fast-growing, low maintenance, evergreen, perennial, self-clinging climber or rambling groundcover that normally grows about 50-100 feet in height. As a ground cover, it typically grows to 6-9 inches tall but spreads over time to 50-100 feet. However, it also forms carpets where there are no suitable objects to climb. Normally English ivy grows in two forms or stages: (1) juvenile stage is the climbing/spreading stage (most often seen) in which plants produces thick, 3-5 lobed, dark green leaves (to 4 inches long ) on non-flowering stems with adventitious roots, and (2) adult stage is the shrubby non-climbing stage in which lobe less, elliptic-ovate, dark green leaves appear on rootless stems that do not spread or climb, but do produce round, umbrella-like clusters of greenish-white flowers in early fall followed by blue-black berries. The plant is found growing in forests, forest edges, rocky places, forest floors, trees, rocky and shady places, waste places, riverbeds, stream banks, cliffs, woodlands, hedges, water courses, riparian areas, wetlands, closed forests, roadsides, gardens and fields. It is often found climbing over trees, posts, walls and fences. It does not thrive in wet or extremely moist areas, but will grow in a wide range of soil ph.

Root

English ivy plants have adventitious roots at their nodes. Roots are generally shallowly rooted, but robust. English ivy also forms aerial, clinging rootlets, allowing it to adhere and climb vertically. Adult English ivy plants form a woody base.

Stems

Stems are slightly woody and produce short aerial roots (i.e. rootlets) that attach to supporting structures. Younger stems are green to purplish or burgundy red in color and hairless (i.e. glabrous) or minutely hairy (i.e. sparsely pubescent).

Leaves

Leaves are alternately arranged along the stems and borne on stalks (i.e. petioles) 2.5-11 cm long. They vary from egg-shaped in outline (i.e. ovate) with entire or wavy margins to heart-shaped (i.e. cordate) or shallowly 3-5 lobed (i.e. palmately lobed). In general, the lower leaves tend to be lobed and the upper leaves tend to be entire. These leaves are 3-15 cm long and 3-10 cm wide and are hairless or nearly so (i.e. glabrous or glabrescent) with rounded to pointed tips (i.e. obtuse to acuminate apices). Their upper surfaces are slightly darker green and glossier than their undersides, and they are sometimes variegated with white or cream. Leaves are long-lived and have a strong smell when crushed. Leaves can be toxic to humans and cattle if ingested. Leaves can also cause contact dermatitis in sensitive individuals.

| Leaf arrangement | Alternate |

| Leaf type | Simple |

| Leaf margin | Lobed |

| Leaf shape | Cordate |

| Leaf venation | Palmate |

| Leaf type and persistence | Evergreen |

| Leaf blade length | 2 to 4 inches |

| Leaf color | Variegated |

| Fall color | No fall color change |

| Fall characteristic | Not showy |

Flowers

The small flowers are arranged in clusters, with all of the flower stalks (i.e. pedicels) originating from the same point (i.e. in umbels). One or more of these clusters may be arranged into larger branched clusters (i.e. into a raceme or panicle of umbels). Each flower has five yellowish-green petals that are 3-5 mm long, but no obvious sepals. They also have five stamens and five partially fused styles that are about 1.5 mm long. Flowering occurs mainly during summer.

| Flower color | White |

| Flower characteristic | Fall flowering |

Fruit

Fertile flowers are followed by berry (it is actually a drupe) 6–8 mm (0.2–0.3 in) in diameter. Fruits are initially green turning to dull bluish-purple or black as it matures. Pulp is purple. The fruit consists of 2-3 whitish seeds. They are normally present during winter and early spring (i.e. from November to January).

The berries, which do not become ripe till the following spring, provide many birds, especially wood pigeons, thrushes and blackbirds with food during severe winters. When ripe, they are about the size of a pea, smooth and succulent. They have a bitter and nauseous taste, and when rubbed, an aromatic and slightly resinous odor.

Thousands of fruits can be produced by an adult plant each year. English ivy berries, mostly when underdeveloped, can be toxic to humans and cattle if ingested. Approximately 70% of the seeds produced are viable.

| Fruit shape | Round |

| Fruit length | Less than .5 inch |

| Fruit cover | Fleshy |

| Fruit color | Unknown |

| Fruit characteristic | Inconspicuous and not showy |

Reproduction and Dispersal

The species reproduces by seed and also vegetatively by a variety of methods. Stems that come into contact with the soil develop roots and can form into new plants (a process called layering). Stem segments that have been separated from the rest of the plant can also take root. Creeping underground stems (i.e. rhizomes) may also be produced.

Seeds are dispersed by birds and other animals that eat the fruit. Seeds and pieces of stem can also be spread in dumped garden waste.

Health Benefits of Common Ivy

The most interesting benefits of English ivy include its ability to reduce inflammation, eliminate congestion, speed healing, soothe the stomach, increase oxygenation and boost the immune system. It also has the ability to heal the skin. Let’s take a closer look at the health benefits of this plant.

1. Have an Anti-cancer Potential

Although research is still ongoing, the many properties that ivy leaves have displayed recommend a significant antioxidant activity, which may also mean that they may have the possible ability to prevent the spread or development of cancer. By possibly eliminating free radicals and preventing mutation and apoptosis, Common ivy leaves may help protect the body from a wide range of chronic diseases, including cancer.

2. Possibly Anti-inflammatory Effects

One of the most well-known benefits of using ivy, particularly English Ivy, is for inflammation issues in the body. If you suffer from arthritis, gout, or rheumatism, you can either consume it in the form of tea or apply the leaves directly to the spot of inflammation. For people who experience discomfort and pain from an injury or surgery, topical application is recommended. This can heal internal inflammation as well, which has a variety of other applications in various bodily systems.

3. Aid in Skin Care

For centuries, people have used common ivy leaves to minimize the pain and infection of burning wounds on the skin. This also works for any open sores or wounds, as there are certain antibacterial properties of its leaves, in addition to the protective nature of the saponins found within the leaves. This can also help relieve the discomfort and irritation of psoriasis, eczema, acne, and other skin-related conditions.

4. Help Detoxify the Body

Early research showed a link between liver and gallbladder function and the use of ivy leaves; this helps the organs function better and release toxins from the body more effectively, thus purifying the blood and reducing strain on these crucial systems.

5. May Relieve Congestion

Common Ivy leaves are commonly used to eliminate respiratory tract congestion and inflammation. They act as an expectorant and can break up the phlegm and mucus in the bronchial system. By eliminating these breeding grounds for pathogens and bacteria, you can improve your overall health and reduce your healing time from illness. This may also make ivy leaves an effective remedy for allergic reactions and asthma, as they reduce the inflammation of those passages.

6. Have Antibacterial Properties

Common ivy also has certain anthelmintic and anti-parasitic qualities, perhaps making it ideal for eliminating intestinal worms and lice. You can clear out your bowels and also topically apply the extract or decoction to the hair for getting rid of those uncomfortable, itching lice as well!

7. Asthma and Bronchitis

English ivy is ideal for reducing cough as well as improving airways. Individuals suffering from asthma, bronchitis, allergies and Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can greatly benefit from it. Consisting mainly of saponins, ivy helps lower the tension of bronchial mucus. This plant also aids oxygen supply in the blood and allows people to breathe freely. Moreover, the bronchial mucosa present produces fluid mucus, which is easier and more comfortable to cough up.

Furthermore, this plant also helps promote oxygen supply to the lungs which makes it effective in facilitating breathing in asthma patients. Additionally, breaking up of phlegm and mucus also eases inflammation and congestion, which makes it excellent for individuals who suffer from seasonal allergies.

Traditional uses and benefits of Common ivy

- It is often used in folk herbal remedies, especially in the treatment of rheumatism and as an external application to skin eruptions, swollen tissue, painful joints, burns and suppurating cuts.

- Recent research has shown that the leaves contain the compound ’emetine which is effective against liver flukes, molluscs, internal parasites and fungal infections.

- Leaves are antibacterial, anti-rheumatic, antiseptic, antispasmodic, astringent, cathartic, diaphoretic, emetic, emmenagogue, stimulant, sudorific, vasoconstrictor, vasodilator and vermifuge.

- Plant is used internally in the treatment of gout, rheumatic pain, whooping cough, bronchitis and as a parasiticide.

- An infusion of the twigs in oil is recommended for the treatment of sunburn.

- The leaves are harvested in spring and early summer, they are used fresh and can also be dried.

- Extracts from the foliage were used medicinally to treat wounds and ulcerative sores, combat lice and fleas, as a narcotic to soothe toothaches, against arthritis and rheumatism and recently it has been shown to be effective against bronchitis.

- In the past, the leaves and berries were taken orally as an expectorant to treat cough and bronchitis.

- In 1597, the British herbalist John Gerard recommended water infused with ivy leaves as a wash for sore or watering eyes.

- It is used for the treatment of respiratory tract diseases with intense mucous formation, respiratory tract infections and in irritating cough which stems from common cold.

- Traditional folk medicine used English ivy internally for liver, spleen and gallbladder disorders, and for gout, arthritis, rheumatism and dysentery.

- Externally it was used for burn wounds, calluses, cellulitis, inflammations, neuralgia, parasitic disorders, ulcers, rheumatic complaints and phlebitis.

- It is most widely used today as a natural treatment for respiratory tract congestion; it is a respiratory catarrh used for symptomatic treatment of chronic inflammatory bronchial conditions.

- Herb consists of saponins which appear to be responsible for preventing spasms in the bronchial area.

- It has been shown that ivy leaf extracts helps to increase oxygen in the lungs, and is an effective anti-inflammatory for bronchial conditions such as asthma and bronchitis

- Folk medicine used ivy leaf poultices externally as a treatment for swollen glands and chronic leg ulcers and topical decoctions have been used as a natural treatment for scabies, lice, and sunburn.

- When used in small amounts, this plant can treat rheumatism and other inflammatory diseases, as well as clean your blood vessels and prevent atherosclerosis, relieve stomach inflammation and regulate your menstrual cycle.

- Sniffing a little bit of English ivy juice has been known to relieve nasal polyps.

- People used the boiled leaves to treat skin ailments and fight scabies and worms in Central Italy.

- Ivy leaf may also help to ease cough, help to relieve sinusitis, a buildup of congestion and catarrh.

How to Consume Ivy

Best and safest way to consume ivy is in a medicinal preparation, but there are a number of different types of remedies made from the ivy plant.

Natural Forms

- Infusion: To brew Common ivy tea, steep ivy leaves in hot water for up to 10 minutes and then strain the ivy out. Tea may be taken up to three times daily, and it helps to relieve respiratory ailments.

- Powder: Common ivy powder can be used to make a tea that helps to improve respiration.

- Poultice: Common ivy leaves may be mixed into a poultice and applied to minor skin wounds to protect against fungal infections and promote healing.

Herbal Remedies & Supplements

- Tincture: Several drops of tincture can be added to another drink to improve respiratory functioning, or the drops may be added to lotion for the plant’s antifungal benefits.

- Extract: One teaspoon of extract may be taken up to three times a day to reduce symptoms of respiratory illness.

- Capsules: Capsules are a quick and simple way to help reduce coughing.

Other Facts

- Yellow and a brown dye are obtained from the twigs.

- Decoction of the leaves is used to restore black fabrics, and also as a hair rinse to darken the hair.

- If the leaves are boiled with soda they are a soap substitute for washing clothes etc.

- It is an excellent ground cover for shady places, succeeding even in the dense shade of trees.

- It is a very effective weed suppresser.

- Plants can be grown along fences to form a hedge.

- Plants have been grown indoors in pots in order to help remove toxins from the atmosphere.

- It is especially good at removing chemical vapors, especially formaldehyde.

- Plants will probably benefit from being placed outdoors during the summer.

- Wood is very hard and can be used as a substitute for Buxus sempervirens (Box), used in engraving etc.

- Wood is very soft and porous and is seldom used except as a strop for sharpening knives.

- It is a popular ornamental and groundcover in residential, commercial and public landscaping, and has been used to control erosion in many parts of the USA.

- Greek priests presented an ivy wreath to newly married couples, as a symbol of fidelity.

- Together with mistletoe and holly, ivy is a traditional herb used to decorate houses for the Christmas season.

Prevention and Control

Due to the variable regulations around (de)registration of pesticides, your national list of registered pesticides or relevant authority should be consulted to determine which products are legally allowed for use in your country when considering chemical control. Pesticides should always be used in a lawful manner, consistent with the product’s label.

Cultural Control

Although the palatability of H. helix to grazing animals in North America is unrecorded, European deer species find it edible and its biomass decreases markedly when ungulate numbers are high. Mammal herbivory could well decrease the plant’s vigor in its invasive range.

Mechanical Control

Killing the aerial portion of H. helix, the seed-producing part of the plant, is easy and only requires the cutting of the stems around the host tree with pruning tools. However, when H. helix grows on tree-ferns, it is not sufficient to cut the stems to kill the plant. All parts of the plant must be removed as H. helix can root and sustain itself in the fibrous tree-fern trunks. The roots of young plants can be easily dug out, particularly when the soil is moist, from the ground around the base of the infected tree, whereas old individuals generally do not re-sprout. When the plant carpets the forest floor, individual stems can be readily pulled off the ground. However, it is essential to remove all runners. Any overlooked live shoot may restart an infestation, thus follow-up monitoring and control is essential. Small or young ivy plants can be pulled off supporting structures or trees, and roots dug out. Soil and native vegetation disturbance must be as limited as possible because this favors the establishment of other invasive species. To avoid re-rooting and resprouting, all material must be carefully removed from the site and disposed of safely. If removal of the plants is not possible, all parts of the plant must be placed off the ground in such a way that they can dry out. Gloves should be worn as skin irritation may follow contact with the plant. One form of prescribed burning has successfully been used to control H. helix. Plants and resprouts are repeatedly burnt with a blowtorch until the plant’s resources are exhausted.

Chemical Control

The mechanical control of H. helix by cutting stems is not always successful particularly if the roots of younger individuals cannot be removed. Then it is advisable to strip the bark, notch the exposed section of the vine and paint on an undiluted herbicide such as glyphosate. This combination of cutting the vine less than 20 cm above ground and an immediate herbicide application may provide better control. Metsulfuron, picloram and glyphosate have all proved successful in Australia. As H. helix leaves are waxy, this often prevents the herbicides, especially hydrophilic compounds such as glyphosate, from permeating the leaves. Thus this plant does not respond well to herbicide spraying, even when a surfactant is added, and non-target native species may be affected in the process. When desirable native vegetation must not be harmed then the stump treatments should be used wherever possible. It is apparent that older plants are more resistant to herbicide treatment and even two applications may not kill them but just reduce growth. In the western USA, immediate spraying of triclopyr following the removal of most leaves and young shoots with a string trimmer has proved successful. However, in other instance, applications of glyphosate, triclopyr and 2, 4-D has proved ineffective or unsatisfactory.

Biological Control

There has been no attempt to identify and introduce biological control agents, and in view of the species’ importance in horticulture in the USA, it is extremely unlikely that any such attempts will be made in that country. In view of the species’ near immunity to pests and diseases in its native range, prospects for biological control are limited. Prasad has reported that the use of a bio herbicide in the form of the fungus Chondrostereum purpureum has been applied to H. helix but its efficacy has yet to be ascertained.

Precaution

- The plant is said to be poisonous in large doses, although the leaves are eaten with impunity by various mammals without any noticeable harmful effects.

- Leaves and fruits consist of the saponic glycoside hederagenin which, if ingested, can cause breathing difficulties and coma.

- Sap can cause dermatitis with blistering and inflammation.

- Excessive doses destroy red blood cells and cause irritability, diarrhea and vomiting.

- Generally when the fruits are eaten, this results in a combination of stomach pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

- helix can cause contact dermatitis, with repeated exposure to wet leaves causing vesicular eruption of the face, hands and arms within 48 hours of contact.

- Leaves can cause severe contact dermatitis in some people.

- Avoid use during pregnancy and breast feeding.

- Excess use may cause Nausea and vomiting.

References:

https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=29393#null

http://www.hear.org/pier/species/hedera_helix.htm

https://pfaf.org/User/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Hedera+helix

https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/26694

https://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/i/ivycom15.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hedera_helix

http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/kew-96659

http://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=276595

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/vine/hedhel/all.html

https://keyserver.lucidcentral.org/weeds/data/media/Html/hedera_helix.htm