| Cockspur grass Quick Facts | |

|---|---|

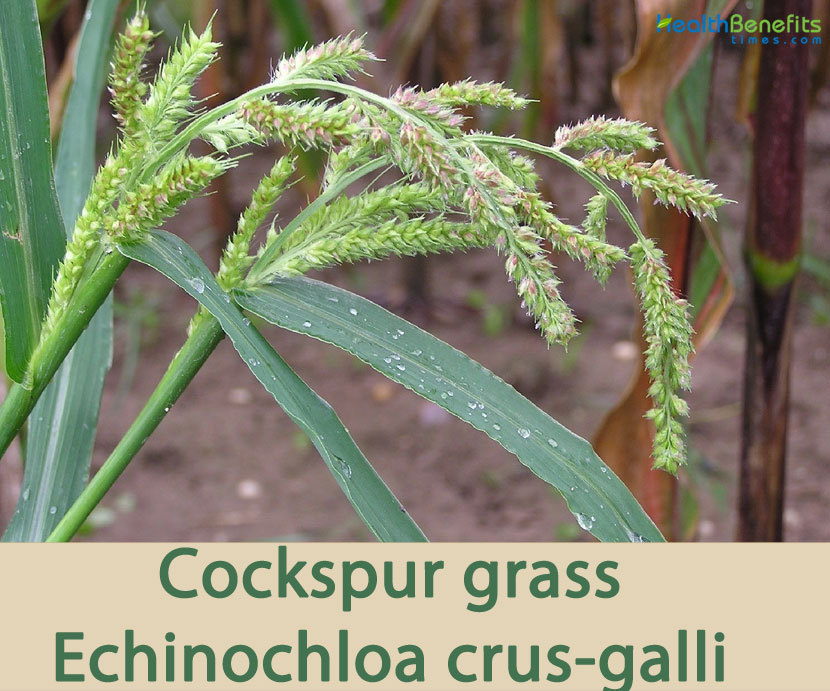

| Name: | Cockspur grass |

| Scientific Name: | Echinochloa crus-galli |

| Origin | Africa, Asia, Australasia; Europe, Northern America and Southern America |

| Colors | Pale yellow |

| Shapes | Seeds are 1.3 to 2.2 mm long, hard, shiny, pale yellow, and rounded on one surface but flattened on the other |

| Health benefits | Support for carbuncles, hemorrhages, sores, indigestion, spleen trouble, cancer, blood sugar, cholesterol and wounds |

| Name | Cockspur grass |

|---|---|

| Scientific Name | Echinochloa crus-galli |

| Native | Africa (Tanzania, Uganda, Sudan, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia, Mozambique, South Africa, Swaziland, Guinea, Senegal, Madagascar and Mauritius); Asia (China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Palestine, Lebanon, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal; Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Philippines); Australasia; Europe (Belarus, Estonia, Ukraine, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark and Norway); Northern America (Mexico); Pacific (U.S. Outlying Islands – Johnston Atoll, Midway Islands, United States – Hawaii, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, French Polynesia and New Caledonia); Southern America (Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, Colombia and Peru) |

| Common Names | Barnyard grass, barnyard millet, barn grass, billion dollar grass, chicken panic grass, cocksfoot panicum, cockspur, cockspur grass, German grass, Japanese millet, Japanese barnyard millet, panic grass, water grass, wild millet, cockspur grass |

| Name in Other Languages | Albanian: Muhar Arabic: Dhunaybah, Deniêbâ Argentina: Arroz silvestre, cresta gallo, grama de agua, gramilla, pasto colorado Australia: Chicken panic Bangladesh: Sharma Belarusian: Bryca (Брыца) Bengali: Buṛāśyāmā ghāsa (বুড়াশ্যামা ঘাস) Bikol: Lagtom Bontoc: Sasablog Brazil: Barbudinho Bulgarian: Petl’ovo proso (петльово просо), daradžan (дараджан) Burmese: Myet ihi Cambodia: Smao bek kbol Catalan: Pota de gall, Serreig, xereix pota de gall Chinese: Bai (稗), Shui bai, Shui bai cao, Bai cao, Ye can zi Cuba: Arrocillo, pata de cao, pata de gallo Czech: Ježatka kurí noha Danish: Almindelig Hanespore, Hanespore, almindelig hanespore, Dutch: Barnyard gierst, Hanepoot, Europese hanenpoot, vogelpoot English: Barnyard grass, Barnyard millet, Cocksfoot, Cockspur, Cock’s foot, Prickly grass, Cockspur grass, Cockshin grass, Cockspur-panic, Water grass, Wild millet, Large barnyard grass, Common barnyard grass, baronet grass, cocksfoot grass, cockshin grass, Japanese millet, jungle rice, common barnyard grass Estonian: Tähk-kukehirss Finnish: Kananhirssi, Rikkakananhirssi French: Panic pied de coq, Pied de coq, Échinochloa pied-de-coq, Oplismène pied-de-coq, Panic des marais, bourgon, crête de coq, ergot de coq, millard, pattes de poule, millet pied-de-coq German: Huehnerhirse, Hühnerhirse, Gewöhnliche Hühnerhirse, Huehnerfuss-Hirse, Hahnenkammhirse, Gemeine, Hahnenfußhirse Ackerhühnerhirse, gemeine Hühnerfennich, gemeine Hühnerhirse, gewöhnlicher Hühnerhirse Hebrew: Dachenit hattamegolim, דָּחְנִית הַתַּרְנְגּוֹלִים Hindi: Sanwak, Samaw, Samak, kayada, Sānvā ghāsa (सांवा घास) Hungarian: Tömött kakaslábfű, közönséges kakaslábfű Ifugao: Baobao Indonesia: Padi burung, dwajan Inupiaq: Pikniq Italian: Giavone, Giavone comune (Switzerland), Pabbio, Panico bastardo, Panico selvatico, Panicastrella (Switzerland), Zampa di gallo, Panicastrella di palude, Panicastrella d’acqua, Panico di risai, pabbione, panicastrella, panico piede di gallo, piè di gallo Japanese: Inu bie (いぬびえ), No bie (ノビエ), Hie, Ke inubie (ケ イヌビエ), ta-in-ubie, ke-inubie, Javanese: Kejawan Kabardian Circassian: BajekӀetsӀyne (БажэкӀэцӀынэ) Kapampangan: Palepalayan Kazakh: Qonaq tarı (Қонақ тары) Khmer: Smao bek kbol Kirghiz: Kürmök (Күрмөк) Korean: Pi (피), pissal (피쌀), dolpi (돌피) Latvian: Parastā gaiļsāre Lithuanian: Paprastoji rietmenė Malay: Padi burong, Padi burung (Indonesia), Rumput kekusa besar, Rumput sambau, Jawan Malayalam: Kavaṭṭa (കവട്ട) Manobo: Dauana Nepali: Saamaa, Tunde saamaa (तुन्दे सामा) Mexico: Arroz Silvestre, gramilla de rastrojo Myanmar: Myet-hi Netherlands: Hanepoot Norwegian: Hønsehirse Occitan: Gaupeilh, pè de hasa, pè de pout Persian: سوروف Philippines: Bayokibok, daua-daua Polish: Chwastnica jednostronna, kurza stopa Portuguese: Capim-arroz, Capim-canevão, Capim-de-capivara, Capim-jaú, Capim-pavão, Capim-pé-de-galinha, canarana; capim-andrequicé; capim-capivara; capim-quicé; milha-maior; milha-pe-de-galo , meã, milhagem, milhã, milhã-grada, milhã-vermelha, pé-de-galinha, barbudinho, capim-da-colônia Romanian: Iarbă bărboasă Russian: Yezhovnik obyknovennyy (Ежовник обыкновенный), Kurinoe proso (Куриное просо), Petush’e proso (Петушье просо), ezhovnik Petush’e proso (ежовник Петушье просо), kuzinoye proso (кузиное просо) Sanskrit: Varuka Serbian: Veliki muhar (велики мухар) Slovak: Ježatka kuria Slovene: Navadna kostreba Spanish: Pata de gallo, Zacate de agua, Pie de gallina, Capín arroz, Mijo de los arrozales, Arrocillo, Gramilla-de-rastrojo, Pasto-colorado, Pé-de-galo, barbarroja, cola de caballo, hualcacho, jaraz fina, mijo japonés, pagarropa, panicello, pasto rayado, pierna o pata de gallo, zacate de agua, arrocilla, hierba hortelana, pierna de gallo, cresta de gallo, grama de agua, panissola, cerreig, hualcacho, mijo japonés, hierba de corral, pega ropa, zacate de agua Sri Lanka: Kutirai-val-pul, martu Sundanese: Jajagoan, Gagajahan Swedish: Hönshirs, Rikkakananhirssi Tagalog: Bayokibok, daua-daua Tajik: Kurmak (Курмак) Tamil: Cāmai (சாமை), Varaku (வரகு) Telugu: Cama (చామ) Sāma (cāma, ṭsāma) Thai: H̄ỵ̂ā k̄ĥāwnk (หญ้าข้าวนก) Yaa kaao nok , Ya plonglaman, hay kai mangda; ya-plong, H̄ỵ̂ā pl̂xng lamān (หญ้าปล้องละมาน) Turkish: Pirinc otu, Dineba, darıcan Ukrainian: Ploskukha zvychayna (плоскуха звичайна) Upper Sorbian: Kurjaca jahlička Urdu: سانوا گھاس Uzbek: Qorakurmak Vietnamese: Cỏ lồng vực, song chong Welsh: Cibogwellt Rhydd |

| Plant Growth Habit | Tall, robust, non-rhizomatous, quick growing, warm-season annual grass |

| Growing Climates | Ditches or stream beds, and in cultivated fields, paddy fields, rice fields, swampy places, along roadsides, ditches, waste places, waterways, wetlands, wet meadows, floodplains, lakeshores and fallow fields |

| Soil | Grows best in rich, moist soils with a high nitrogen content, but it can also thrive on sands and loamy soils |

| Plant Size | 0.8–1.5 m tall |

| Root | Fibrous root system |

| Stem | Stems may be solitary or in small tufts, erect or reclining at the base, up to 6.6 feet tall |

| Leaf | Elongated leaves are alternate, 5-50 cm (2-20 in.) long, 6-22 mm (¼-¾ in.) wide, flat, deep green or somewhat purplish, hairless or with 1 to 3 solitary hairs near the base of the blade |

| Flowering season | July to September |

| Flower | The panicle (loose and non-symmetrical cluster of flowers) is green or purple, densely branched, protruding, slightly drooping and can range from 8-30 cm in length. The erect branches are sessile (attached to the main stem) and 5 cm long. |

| Fruit Shape & Size | Grains (seeds) are 1.3 to 2.2 mm long, hard, shiny, pale yellow, and rounded on one surface but flattened on the other |

| Fruit Color | Pale yellow |

| Propagation | By seed |

| Season | August to October |

| Precautions |

|

Plant Description

Cockspur grass is a tall, robust, non-rhizomatous, quick growing, warm-season annual grass that normally grows about 0.8–1.5 m tall. The plant is found growing in ditches or stream beds, in cultivated fields, paddy fields, swampy places, along roadsides, ditches, waste places, waterways, wetlands, wet meadows, floodplains, lakeshores and fallow fields. The plant grows best in rich, moist soils with high nitrogen content, but it can also thrive on sands and loamy soils. The plant has fibrous root system. Stems are erect, hairless, spreading or lying horizontally on the ground and bending upwards but rooting from nodes in contact with the soil. Stems are 5-150 cm (2in.-5ft) long, coarse, smooth, usually round in cross-section but occasionally much flattened.

Leaves

Elongated leaves are alternate, 5-50 cm (2-20 in.) long, 6-22 mm (¼-¾ in.) wide, flat, deep green or somewhat purplish, hairless or with 1 to 3 solitary hairs near the base of the blade. Leaf sheaths are usually hairless, occasionally with a few hairs along the edges, and lower sheaths are commonly purplish. The ligule (membrane where the leaf joins the sheath) is lacking, the juncture smooth and pale to purplish. Nodes are hairless; sometimes the lower nodes are minutely hairy.

Flower

The panicle (loose and non-symmetrical cluster of flowers) is green or purple, densely branched, protruding, slightly drooping and can range from 8-30 cm in length. The erect branches are sessile (attached to the main stem) and 5 cm long. Ovoid spikelets (individual flower with a cluster) are pale green to dull purple, densely arranged on branches, and are short-bristly along veins. Fertile lemma (specialized bracts enclosing a floret) is pale yellow, ovate to elliptic, acute, lustrous, and smooth and 3-3.5 mm long. Flowering normally takes place in between July to September.

Fruit

The whole spikelet drops away when mature, leaving a naked stem behind. Grains (seeds) are 1.3 to 2.2 mm long, hard, shiny, pale yellow, and rounded on one surface but flattened on the other. It is enclosed within the persistent lemma and palea.

Traditional uses and benefits of Cockspur grass

- Barnyard grass is a folk remedy for treating carbuncles, hemorrhages, sores, spleen trouble, cancer and wounds.

- The shoots and/or the roots are applied as a styptic to wounds.

- The plant is a tonic, acting on the spleen.

- In ethno medicine, it has been used to cure spleen diseases.

- The roots are boiled to cure indigestion in the Philippines.

- Barnyard grass effectively lowers blood sugar and cholesterol when consumed, according to Yonhap.

Culinary Uses

- Seed can be consumed after being cooked.

- It is used as millet; it can be cooked whole or be ground into flour before use.

- It has a good flavor and can be used in porridges, macaroni, dumplings etc.

- The seed is rather small, though fairly easy to harvest.

- Young shoots, stem tips and the heart of the culm can be consumed raw or cooked.

- Food-type barnyard millets are used as staple.

- The grain is parched, roasted, boiled, ground into flour.

- It can be popped like popcorn.

- In Japan, it is used to make macaroni and dumplings.

- The grain is roasted and used as a coffee substitute.

- Indian barnyard millet can safely replace rice grain for some traditional preparations in India.

- In the Hisar district of the Indian state of Haryana the seeds of this grass are commonly eaten with cultivated rice grains to make rice pudding or khir on Hindu fast days.

Other Facts

- The plant is sometimes used, especially in Egypt, for the reclamation of saline and alkaline areas.

- A single plant may produce as many as 40,000 seeds

- It is also suited for silage, but not for hay.

- It is fed green to animals and provides fodder throughout the year; hay made from this plant can be kept up to 6 years.

- Grass is also used for reclamation of saline and alkaline areas, particularly in Egypt.

- This grass is readily eaten by wild animals: rabbits, deer, waterfowls, etc.

- Barnyard grass completes its lifecycle in 42 to 64 days and it produces up to 42.000 seed per season.

Prevention and Control

Due to the variable regulations around (de)registration of pesticides, your national list of registered pesticides or relevant authority should be consulted to determine which products are legally allowed for use in your country when considering chemical control. Pesticides should always be used in a lawful manner, consistent with the product’s label.

Cultural Control

Hand weeding can be effective if adequate labor is available, but when young, E. crus-galli is hard to distinguish from young rice, making hand weeding very difficult.

Bhatia et al. found that high populations of E. crus-galli in rice fields were due to new seed added every season. Pot and field studies revealed that 97.7% of the seed reserves were exhausted in one season, and by the third season the soil was free of viable seed. Farmyard manure and other organic fertilizers can be major sources of weed seeds, including E. crus-galli, but these lose their viability after being subjected to anaerobic fermentation for one month.

Deep water flooding (up to 22 cm) can provide good control of E. crus-galli in rice. Water-sowing, a method of direct-broadcast sowing of rice began in California, USA, during the 1920s as a cultural method to control E. crus-galli var. crus-galli by continuously-flooded water management.

The use of Azolla in transplanted irrigated rice failed to suppress E. crus-galli var. hispidula, which increased by 226.4%, whereas some weeds were suppressed. Field and laboratory studies in Asia have indicated that some rice cultivars exhibited strong allopathic effects against E. crus-galli.

Chung (1995) found that dried lucerne residues inhibited germination and seedling growth of the weeds E. crus-galli, Siegesbechia viridis and Portulaca oleracea, as well as several crops.

Different tillage systems in soybean and maize fields in northern Italy have been shown to profoundly alter the weed community, with species linked to increased disturbance being annuals, such as E. crus-galli.

Biological Control

Tsukamoto describes using virulent isolates of Exserohilum monoceras and Cochliobolus sativus to achieve an approximate 80% reduction in dry matter of different botanical varieties of E. crus-galli. Zhang studied optimal temperature and dew-point for the development of E. monoceras on E. crus-galli and E. colonum after inoculation. E. monoceras continues to be the most studied potential bio control agent, with Tosiah et al. evaluating its effects at different leaf development stages and on different varieties of E. crus-galli. In surveys in Malaysia, Tosiah et al. found E. monoceras, E. longirostratum and Curvularia lunata among the fungi present on diseased E. crus-galli plants. E. monoceras was consistently found associated with the disease, virulent, stable and with the ability to produce spores profusely in culture, suggesting that it could be used as a biocontrol agent.

Li Jing et al. (2013) evaluated Cochliobolus lunatus as a potential mycoherbicide for barnyard grass, and found that one particular virulent strain was highly pathogenic at the 1- to 2.5-leaf stages, and was safe to rice. It is suggested that this strain could be a potential mycoherbicide for barnyard grass control in paddy fields in the future. Zhang et al. found high mortality in E. crus-galli from a strain of Bipolaris eleusines, with no pathogenicity to rice, maize or wheat. Jyothi et al. (2013) report trials with C. lunatus and Alternaria alternata, achieving 100% mortality of the target weed and no effect on rice.

In a review of research progress on mycoherbicides for control of E. crus-galli in rice in China, Zhang et al. (2011) suggest that mass production and formulation technologies have proved to be the major stumbling blocks that hinder bio-herbicide development.

A zearalenone derivative extracted from Drechslera portulacae, a pathogen of purslane (Portulaca oleracea), inhibited root length of E. crus galli and Abutilon threophrasti in pot experiments.

Chemical Control

The use of herbicides against E. crus-galli has been widespread and it is susceptible to a wide range of herbicides used in rice cultivation, including butachlor, butralin, cinmethylin, chlomethoxyfen, fenoxaprop, glyphosate, molinate, oxadiazon, oxyfluorfen, paraquat, pendimethalin, piperophos, pretilachlor, propanil, quinclorac and thiobencarb.

Field trials in the Korea Republic showed that 2 applications of herbicide using butachlor or thiobencarb 3 days after sowing and followed by tank-mixed bentazone + quinclorac 50 days after sowing were necessary to control E. crus-galli. Studies in the USA showed late-season control with pendimethalin + quinclorac was more effective than pendimethalin, quinclorac, thiobencarb, or pendimethalin + thiobencarb. Control using pendimethalin, quinclorac and pendimethalin + thiobencarb exceeded that with thiobencarb. Propanil + molinate controlled E. crus-galli more effectively than propanil.

The introduction and spread of E. oryzoides and E. phyllopogon in California, USA, have caused rice farmers to rely on herbicides such as molinate or propanil to protect the crop from serious losses in yield and grain quality. Propanil-resistant E. crus-galli was initially found in Arkansas, USA, during 1990, and was the result of dependence upon propanil for a long period. Propanil formulations tank-mixed with quinclorac, thiobencarb or pendimethalin were effective for controlling resistant and susceptible biotypes when applied post-emergence, whereas quinclorac and mixtures of quinclorac with pendimethalin and thiobencarb were very effective when applied pre-emergence. Malik et al. (1996) reported herbicide resistance in E. crus-galli against butachlor and thiobencarb. In Spain, E. crus-galli var. hispidula (in rice) showed resistance to quinclorac, whereas E. crus-galli var. crus-galli (in maize), showed resistance to atrazine. An analysis of 4 isoenzymes from 3 different biotypes of E. crus-galli with tolerance to quinclorac from Spain showed different enzyme PAGE patterns.

In the Philippines, Juliano et al. (2010) confirmed for the first time that E. crus-galli populations were resistant to both chloroacetamide (butachlor)- and acetanilide (propanil)-group herbicides commonly used in direct-seeded rice in the Philippines. In Arkansas, Riar et al. (2012) describe resistance to acetolactate synthase (ALS)-inhibiting herbicides. Panozzo et al. (2013) also found resistance to at least one ALS-inhibiting herbicide in 14 E. crus-galli populations in Italy. It is suggested that ALS-resistant, and especially ALS- and ACCase multiple resistant barnyard grass are threatening the sustainability of Italian rice crops due to the lack of alternative post-emergence herbicides.

Ma et al. (2014) discuss the control of quinclorac-resistant E. crus-galli in China, and found that that penoxsulam and bispyribac-sodium gave effective control.

References:

https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=502210#null

http://www.hear.org/pier/species/echinochloa_crus_galli.htm

https://npgsweb.ars-grin.gov/gringlobal/taxon/taxonomydetail?id=14823

https://pfaf.org/user/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Echinochloa+crus-galli

https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/20367

https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/ECHCG

http://www.theplantlist.org/tpl1.1/record/kew-410191

https://keyserver.lucidcentral.org/weeds/data/media/Html/echinochloa_crusgalli.htm

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/graminoid/echcru/all.html

https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/GreatLakes/FactSheet.aspx?Species_ID=2664

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Echinochloa_crus-galli

https://www.feedipedia.org/node/720

https://www.nordic-baltic-genebanks.org/gringlobal/taxonomydetail.aspx?id=14823

https://www.minnesotawildflowers.info/grass-sedge-rush/barnyard-grass

http://www.flowersofindia.net/catalog/slides/Barnyard%20Grass.html

https://spain.inaturalist.org/taxa/60283-Echinochloa-crus-galli

https://plants.usda.gov/home/plantProfile?symbol=ECCR