The alimentary tract, also known as the digestive tract or gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is a continuous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus, responsible for the ingestion, digestion, absorption, and excretion of food and nutrients. It includes several key organs and structures such as the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, each playing a specific role in the digestive process. The alimentary tract is lined with various types of epithelial cells and contains specialized glands that secrete enzymes and other substances to aid in the breakdown and absorption of food. Additionally, it houses a complex microbiome that interacts with the host’s immune system and contributes to overall health. The tract’s anatomy and function can vary significantly among different species, reflecting their dietary habits and ecological niches

The alimentary tract, also known as the digestive tract or gastrointestinal (GI) tract, is a continuous tube that extends from the mouth to the anus, responsible for the ingestion, digestion, absorption, and excretion of food and nutrients. It includes several key organs and structures such as the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine, each playing a specific role in the digestive process. The alimentary tract is lined with various types of epithelial cells and contains specialized glands that secrete enzymes and other substances to aid in the breakdown and absorption of food. Additionally, it houses a complex microbiome that interacts with the host’s immune system and contributes to overall health. The tract’s anatomy and function can vary significantly among different species, reflecting their dietary habits and ecological niches

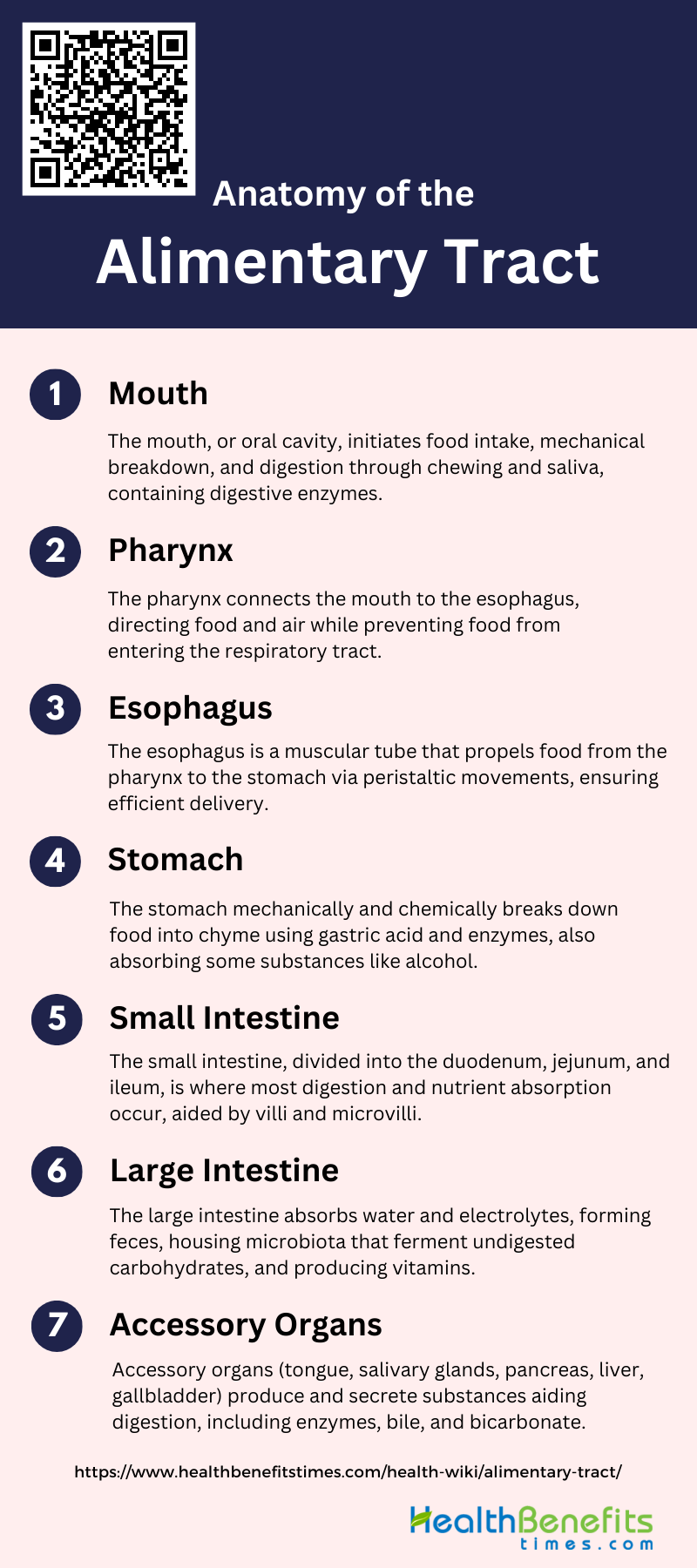

Anatomy of the Alimentary Tract

Below is a detailed overview of the key components of the alimentary tract:

1. Mouth

The mouth, or oral cavity, is the initial part of the alimentary tract where food intake occurs. It is divided into the vestibule, located between the lips and teeth, and the oral cavity proper, which lies behind the teeth. The mouth is lined with a stratified mucous membrane and features structures such as the hard and soft palates, with the uvula hanging from the latter. The primary functions of the mouth include the mechanical breakdown of food through chewing and the initiation of digestion via saliva, which contains enzymes that begin the chemical breakdown of food.

2. Pharynx

The pharynx, or throat, serves as a passageway for both food and air. It connects the mouth to the esophagus and the nasal cavities to the larynx. The pharynx is divided into three regions: the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx. During swallowing, the pharynx plays a crucial role in directing the food bolus from the mouth to the esophagus while preventing food from entering the respiratory tract. This process involves coordinated muscle contractions and the closure of the epiglottis to protect the airway.

3. Esophagus

The esophagus is a muscular tube that transports food from the pharynx to the stomach. It is lined with a stratified squamous epithelium and features longitudinal folds that allow it to expand as food passes through. The esophagus is composed of four layers: serosa, muscularis, submucosa, and mucosa. The primary function of the esophagus is to propel the food bolus towards the stomach through peristaltic movements, ensuring efficient and timely delivery of ingested materials.

4. Stomach

The stomach is a muscular, sac-like organ located in the upper abdomen. It is divided into several regions: the cardiac region, fundus, body, and pyloric region. The stomach’s primary functions include the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food. Gastric glands in the stomach lining secrete hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes, which convert the food bolus into a semi-liquid substance called chyme. The stomach also plays a role in the absorption of certain substances, such as alcohol and some medications.

5. Small Intestine

The small intestine is a long, coiled tube where most digestion and nutrient absorption occur. It is divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The inner surface of the small intestine is lined with villi and microvilli, which increase the surface area for absorption. Digestive enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver aid in the breakdown of nutrients, which are then absorbed through the mucosal epithelial cells into the bloodstream. The small intestine is crucial for the efficient absorption of carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals.

6. Large Intestine

The large intestine, or colon, is responsible for absorbing water and electrolytes from indigestible food residues and forming solid waste (feces) for elimination. It is divided into several sections: the cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and rectum. The large intestine also houses a diverse microbiota that plays a role in fermenting undigested carbohydrates, producing vitamins, and protecting against pathogens. The final waste products are stored in the rectum until they are expelled through the anus.

7. Accessory Organs

The accessory organs of the digestive system include the tongue, salivary glands, pancreas, liver, and gallbladder. These organs produce and secrete various substances that aid in digestion. The salivary glands produce saliva, which contains enzymes that initiate carbohydrate digestion. The liver produces bile, which emulsifies fats, and the gallbladder stores and concentrates bile. The pancreas secretes digestive enzymes and bicarbonate into the small intestine to neutralize stomach acid and further digest nutrients. These accessory organs work in concert with the alimentary tract to ensure efficient digestion and nutrient absorption.

Physiological Processes of Alimentary Tract

Involves a series of complex physiological processes that ensure the digestion and absorption of nutrients. These processes are crucial for maintaining overall health and involve various organs working in harmony. Below is a list of the key physiological processes of the alimentary tract:

1. Ingestion

Ingestion is the initial phase of the alimentary process where food and liquids are taken into the body through the mouth. This process involves the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal regions, which work together to transport the ingested material to the stomach. The act of swallowing, or deglutition, is a complex mechanism that ensures the safe passage of food from the mouth to the stomach, preventing aspiration into the respiratory tract. Accessory organs such as the tongue and salivary glands play crucial roles in this phase by aiding in the mechanical breakdown and lubrication of food, facilitating its smooth transit.

2. Mechanical Processing

Mechanical processing involves the physical breakdown of food into smaller particles, making it easier for enzymes to act on them during digestion. This process includes mastication (chewing) in the mouth, churning in the stomach, and segmentation in the intestines. The gizzard, a specialized structure in some animals, also plays a significant role in the comminution of food particles. The morphology of the gizzard’s epithelium, which consists of cells with stout microvilli, reflects its function in grinding food. Mechanical processing ensures that food is adequately mixed with digestive juices, enhancing the efficiency of subsequent chemical digestion.

3. Digestion

Digestion is the biochemical process where complex food substances are broken down into simpler molecules that can be absorbed by the body. This process is facilitated by digestive enzymes secreted by various glands, including the salivary glands, pancreas, and liver. These enzymes act on proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, breaking them down into amino acids, fatty acids, and simple sugars, respectively1. Intracellular digestion, particularly in the digestive gland of certain organisms, also plays a crucial role in this process. The transformation of the food bolus into chyme in the stomach and its further breakdown in the small intestine are key steps in digestion.

4. Secretion

Secretion involves the release of digestive juices and enzymes that aid in the breakdown of food. Various glands along the alimentary tract, including the salivary glands, pancreas, and liver, secrete substances that facilitate digestion. For instance, the pancreas secretes digestive enzymes, while the liver produces bile, which emulsifies fats, making them easier to digest. The histochemical properties and ultrastructure of gland cells suggest that some cells produce multiple substances, including enzymes. These secretions are crucial for the chemical digestion of food, ensuring that nutrients are broken down into absorbable forms.

5. Absorption

Absorption is the process by which the end products of digestion, along with water, minerals, and vitamins, pass through the intestinal mucosa into the blood and lymphatic systems. This primarily occurs in the small intestine, where the mucosal epithelial cells facilitate the transfer of nutrients from the lumen of the intestine into the bloodstream. The presence of ciliated cells and cells with microvilli in the alimentary tract enhances the absorption process by increasing the surface area available for nutrient uptake. Efficient absorption is essential for the body to utilize the nutrients derived from food.

6. Excretion

Excretion is the final phase of the alimentary process, involving the elimination of indigestible substances and waste products from the body. The remnants of digestion, primarily composed of fiber and bacteria, are expelled as feces through the rectum and anus. The mid- and post-intestine regions, which contain villi cells with extensive basal labyrinths, play a role in absorbing water and ions from the fecal matter, ensuring that the body retains essential fluids and electrolytes. This process is vital for maintaining homeostasis and preventing the accumulation of waste products in the body.

Common Disorders of the Alimentary Tract

Below is a list of some common disorders of the alimentary tract:

1. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD) is a prevalent condition characterized by heartburn and acid regurgitation. It affects a significant portion of the population, with prevalence rates ranging from 2.5% to over 25%. GERD can be classified into erosive reflux disease (ERD) and non-erosive reflux disease (NERD), with NERD being more common. Risk factors include heavy smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and certain dietary habits. Complications can include Barrett’s esophagus, a pre-cancerous condition.

2. Peptic Ulcers

Peptic ulcers are sores that develop on the lining of the stomach, small intestine, or esophagus. They are primarily caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Symptoms include burning stomach pain, bloating, and heartburn. Complications can include bleeding, perforation, and gastric obstruction. Treatment typically involves antibiotics to eradicate H. pylori and medications to reduce stomach acid.

3. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) encompasses two main conditions: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Both are chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss, and fatigue. The exact cause is unknown, but it involves an abnormal immune response. Treatment focuses on reducing inflammation through medications, lifestyle changes, and sometimes surgery.

4. Ulcerative Colitis

Ulcerative colitis is a type of IBD that specifically affects the colon and rectum. It causes long-lasting inflammation and ulcers in the digestive tract. Symptoms include diarrhea with blood or pus, abdominal pain, and urgency to defecate. The condition can lead to severe complications like colon cancer. Treatment includes anti-inflammatory drugs, immune system suppressors, and sometimes surgery to remove the colon.

5. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a common disorder affecting the large intestine. It is characterized by symptoms such as cramping, abdominal pain, bloating, gas, and diarrhea or constipation. The exact cause is unknown, but it is believed to involve a combination of gut-brain axis issues, gut motility problems, and heightened sensitivity to pain. Management includes dietary changes, stress relief, and medications to alleviate symptoms.

6. Celiac Disease

Celiac disease is an autoimmune disorder where ingestion of gluten leads to damage in the small intestine. Symptoms include diarrhea, bloating, gas, fatigue, and anemia. Long-term complications can include malnutrition, osteoporosis, and an increased risk of certain cancers. The only effective treatment is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet.

7. Gallstones

Gallstones are hardened deposits of digestive fluid that can form in the gallbladder. They can cause severe pain, jaundice, and infection. Risk factors include obesity, high-fat diet, and certain medical conditions. Treatment options include medications to dissolve gallstones or surgical removal of the gallbladder.

8. Lactose Intolerance

Lactose intolerance is the inability to digest lactose, a sugar found in milk and dairy products. Symptoms include bloating, diarrhea, and abdominal cramps after consuming dairy. It is caused by a deficiency of lactase, the enzyme needed to digest lactose. Management involves dietary changes to limit or avoid lactose-containing foods.

9. Diverticulosis and Diverticulitis

Diverticulosis involves the formation of small pouches (diverticula) in the colon wall. When these pouches become inflamed or infected, it is called diverticulitis. Symptoms of diverticulitis include severe abdominal pain, fever, and changes in bowel habits. Treatment ranges from dietary changes and antibiotics to surgery in severe cases.

10. Cancer

Cancers of the alimentary tract include esophageal, stomach, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers. Symptoms vary depending on the type and stage but can include weight loss, abdominal pain, changes in bowel habits, and bleeding. Risk factors include smoking, alcohol use, diet, and genetic predisposition. Treatment options include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapies.

Diagnosis of Alimentary Tract

The diagnosis of alimentary tract disorders involves a comprehensive approach that includes clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, and imaging studies. Accurate diagnosis is crucial for effective treatment and management of these conditions. Below are the key steps and methods used in the diagnostic process:

1. Endoscopy

Endoscopy is a crucial diagnostic tool for examining the alimentary tract, allowing direct visualization of the mucosal surface. It is particularly effective in identifying lesions, tumors, and inflammatory conditions. Endoscopic procedures can be performed on both the upper and lower parts of the digestive tract, providing real-time images that help in the diagnosis and management of various gastrointestinal diseases. Additionally, endoscopy can be combined with biopsy techniques to obtain tissue samples for histopathological examination, enhancing diagnostic accuracy.

2. Imaging Tests

Imaging tests such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasound (US) play a significant role in diagnosing alimentary tract conditions. CT scans are particularly useful for evaluating wall thickening and differentiating between benign and malignant processes based on specific imaging characteristics. MRI and US are also valuable, especially in emergency settings like alimentary tract perforations, where they help in rapid and accurate diagnosis. These imaging modalities provide detailed information about the extent and nature of pathological conditions, aiding in effective treatment planning.

3. Blood Tests

Blood tests are essential in the diagnostic workup of alimentary tract diseases. They can reveal signs of inflammation, infection, anemia, and other systemic conditions that may be associated with gastrointestinal disorders. For instance, elevated white blood cell counts and erythrocyte sedimentation rates can indicate inflammatory or infectious processes, while low hemoglobin levels may suggest bleeding or anemia. Blood tests are often used in conjunction with other diagnostic methods to provide a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s condition.

4. Stool Tests

Stool tests are non-invasive diagnostic tools used to detect various conditions affecting the alimentary tract. They can identify the presence of blood, pathogens, and other abnormalities in the stool, which may indicate infections, inflammatory bowel disease, or colorectal cancer. Stool tests are particularly useful for screening and early detection of gastrointestinal diseases, allowing for timely intervention and management. These tests are often part of a broader diagnostic approach that includes endoscopy and imaging studies.

5. Biopsy

Biopsy involves the removal of tissue samples from the alimentary tract for microscopic examination. It is a definitive diagnostic method for identifying neoplastic and inflammatory conditions. Endoscopic biopsy, often performed during an endoscopic examination, allows for targeted sampling of suspicious areas. Despite its limitations, such as the small size and superficial nature of the samples, biopsy remains a critical tool in diagnosing and staging gastrointestinal diseases, providing essential information for treatment planning.

6. pH Monitoring

pH monitoring is a specialized diagnostic test used to measure the acidity levels in the esophagus and stomach. It is particularly useful in diagnosing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and other acid-related disorders. By continuously recording pH levels over a 24-hour period, this test helps in correlating symptoms with acid exposure, thereby guiding appropriate therapeutic interventions. pH monitoring is often used in conjunction with other diagnostic methods to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s condition.

Treatment Modalities of Alimentary Tract

The treatment of alimentary tract disorders involves a variety of approaches tailored to the specific condition and patient needs. These modalities range from dietary modifications and pharmacological interventions to surgical procedures and advanced therapeutic techniques. Below is a comprehensive list of treatment options commonly employed in managing alimentary tract conditions:

1. Dietary and Lifestyle Changes

Dietary and lifestyle changes play a crucial role in managing alimentary tract disorders. For instance, the consumption of dietary fiber and prebiotics can significantly modulate the gut microbiota, promoting the growth of beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. These changes can improve gut health by enhancing microbial balance and producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that support intestinal health. Additionally, hyperalimentation, which involves providing complete intravenous nutrition, has been used to manage severe cases of Crohn’s disease by placing the gastrointestinal tract at rest and improving nutritional status before surgery. These dietary interventions are essential for maintaining gut health and managing symptoms of gastrointestinal disorders.

2. Medications

Medications are a cornerstone in the treatment of alimentary tract disorders, including inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Standard medical treatments often involve the use of 5-aminosalicylates, sulfasalazine, and corticosteroids to induce and maintain remission. However, the efficacy of these medications can vary, and some patients may experience adverse effects. Therefore, ongoing research is exploring alternative treatments, such as probiotics, which have shown potential in modulating gut microbiota and reducing inflammation, although their effectiveness in preventing disease recurrence remains inconclusive7.

3. Surgical Interventions

Surgical interventions are often necessary for patients with severe or refractory alimentary tract disorders. For example, ileo-caecal resection is a common procedure for Crohn’s disease patients who do not respond to medical therapy. Postoperative management is critical, as early endoscopic recurrence is frequent. Studies have investigated the use of probiotics like Lactobacillus johnsonii and VSL#3 to prevent recurrence, but results have been mixed, indicating the need for further research7. Additionally, preoperative hyperalimentation can improve surgical outcomes by enhancing nutritional status and promoting positive nitrogen balance.

4. Endoscopic Procedures

Endoscopic procedures are minimally invasive techniques used for both diagnostic and therapeutic purposes in alimentary tract disorders. They are essential for monitoring disease progression, assessing treatment efficacy, and performing interventions such as polyp removal or stricture dilation. For instance, endoscopic evaluation is crucial in assessing the recurrence of Crohn’s disease post-surgery. Despite the potential benefits, studies have shown that probiotics like Lactobacillus johnsonii and VSL#3 have not significantly reduced endoscopic recurrence rates, highlighting the complexity of managing postoperative Crohn’s disease.

5. Probiotics and Supplements

Probiotics and supplements are increasingly being explored as adjunct therapies for alimentary tract disorders. Probiotics, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, have been studied for their potential to modulate gut microbiota, enhance gut barrier function, and reduce inflammation. While some studies have shown modest benefits in reducing disease activity in conditions like ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer, others have found no significant differences in remission rates compared to placebo. The use of prebiotics, which selectively stimulate the growth of beneficial gut bacteria, also shows promise in improving gut health and metabolic functions. Further research is needed to establish the efficacy and optimal use of these supplements in clinical practice.

Preventive measures for Alimentary Tract Health

Maintaining the health of your alimentary tract is crucial for overall well-being. Implementing preventive measures can help avoid common digestive issues and promote a healthy gut. Here are some key strategies to keep your alimentary tract in optimal condition:

1. Stay Hydrated

Staying hydrated is crucial for maintaining a healthy alimentary tract. Adequate water intake helps in the smooth passage of food through the digestive system and prevents constipation. Proper hydration ensures that the mucosal lining of the intestines remains moist, which is essential for nutrient absorption and waste elimination. Studies have shown that drinking sufficient water can aid in the prevention of diverticular disease by promoting regular bowel movements and reducing the risk of colonic outpouchings.

2. Include Fiber in Your Diet

Dietary fiber plays a significant role in maintaining gastrointestinal health. Fiber increases the bulk of the stool and promotes regular bowel movements, which can prevent constipation and reduce the risk of developing diverticular disease. Additionally, fiber serves as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial gut bacteria and promoting a healthy microbiota. This can lead to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that support gut health and reduce inflammation.

3. Eat a Balanced Diet

A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins provides essential nutrients that support overall digestive health. Such a diet ensures the intake of vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants that protect the gut lining and promote a healthy microbiome. A well-balanced diet can also help in maintaining a healthy weight, which is crucial for preventing gastrointestinal disorders such as colorectal cancer.

4. Eat Foods with Probiotics or Take Probiotic Supplements

Probiotics are beneficial bacteria that can help maintain the balance of the gut microbiota. Consuming foods rich in probiotics, such as yogurt, kefir, and fermented vegetables, or taking probiotic supplements can enhance gut health by preventing bacterial translocation and improving intestinal barrier function. Probiotics have been shown to reduce the incidence of antibiotic-associated diarrhea and may help in managing conditions like irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel diseases.

5. Eat Mindfully and Chew Your Food

Mindful eating and thorough chewing of food can significantly impact digestive health. Chewing food properly breaks it down into smaller particles, making it easier for the digestive enzymes to act on them. This can prevent issues like indigestion and bloating. Eating mindfully also helps in recognizing hunger and fullness cues, which can prevent overeating and promote better digestion.

6. Regular Exercise

Regular physical activity is beneficial for maintaining a healthy digestive system. Exercise stimulates intestinal contractions, which can help in moving food through the digestive tract more efficiently and prevent constipation. It also helps in maintaining a healthy weight, reducing the risk of gastrointestinal disorders such as colorectal cancer and diverticular disease.

7. Avoid Tobacco and Limit Alcohol

Tobacco and excessive alcohol consumption can have detrimental effects on the digestive system. Smoking has been linked to an increased risk of gastrointestinal disorders, including peptic ulcers and Crohn’s disease. Alcohol can irritate the stomach lining and disrupt the balance of gut bacteria, leading to conditions like gastritis and liver disease. Limiting these substances can significantly improve digestive health.

8. Manage Your Stress

Chronic stress can negatively impact the digestive system by altering gut motility and increasing the risk of conditions like irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Stress management techniques such as mindfulness, meditation, and regular physical activity can help in maintaining a healthy gut. Probiotics have also been shown to mitigate the adverse effects of stress on the intestinal barrier.

9. Limit Processed Foods

Processed foods often contain high levels of unhealthy fats, sugars, and additives that can disrupt the balance of gut bacteria and contribute to digestive issues like constipation and inflammation. Limiting the intake of processed foods and opting for whole, unprocessed foods can promote a healthier gut microbiota and reduce the risk of gastrointestinal disorders.

10. Regular Medical Check-Ups

Regular medical check-ups are essential for early detection and prevention of gastrointestinal disorders. Routine screenings, such as colonoscopies, can help in identifying conditions like colorectal cancer at an early stage when they are most treatable. Regular check-ups also provide an opportunity to discuss any digestive symptoms with a healthcare provider and receive appropriate guidance and interventions.