Affective disorders, also known as mood disorders, are a group of mental health conditions characterized by significant and persistent disturbances in an individual’s emotional state or mood. These disorders can manifest as periods of extreme sadness (depression), elevated or irritable mood (mania or hypomania), or a combination of both. The two main types of affective disorders are depressive disorders, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder, and bipolar disorders, which involve alternating episodes of mania/hypomania and depression. Affective disorders can significantly impact an individual’s ability to function in daily life, relationships, and work, making proper diagnosis and treatment crucial for managing symptoms and improving quality of life.

Affective disorders, also known as mood disorders, are a group of mental health conditions characterized by significant and persistent disturbances in an individual’s emotional state or mood. These disorders can manifest as periods of extreme sadness (depression), elevated or irritable mood (mania or hypomania), or a combination of both. The two main types of affective disorders are depressive disorders, such as major depressive disorder and persistent depressive disorder, and bipolar disorders, which involve alternating episodes of mania/hypomania and depression. Affective disorders can significantly impact an individual’s ability to function in daily life, relationships, and work, making proper diagnosis and treatment crucial for managing symptoms and improving quality of life.

Types of Affective Disorders

Understanding the different types of affective disorders is essential for identifying symptoms and seeking proper treatment. One of the most common affective disorders is presented here.

1. Depression

Depression, a major subclass of affective disorders, is characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, loss of interest, and various physical and emotional problems. It is often classified into unipolar and bipolar forms, with unipolar depression involving only depressive episodes and bipolar disorder involving both depressive and manic episodes. The epidemiology of depression has been extensively studied, revealing it as one of the most common mental health conditions in Europe. Genetic studies have shown that depression is a multifactorial disease influenced by both genetic and environmental factors, with heritability estimates around 40%. The classification of depression has evolved over time, with modern systems like DSM-IV providing more reliable diagnostic criteria.

2. Bipolar Disorder (BD)

Bipolar Disorder (BD) is characterized by alternating episodes of mania and depression. During manic episodes, individuals experience elevated mood, increased activity, and other symptoms such as decreased need for sleep and grandiosity. Bipolar disorder is further divided into Bipolar I, which includes full-blown manic episodes, and Bipolar II, which involves hypomanic episodes that are less severe. Genetic research indicates a high heritability for BD, estimated between 58-85%. The disorder’s clinical picture is complex, with symptoms varying significantly between manic and depressive phases. Modern classification systems like DSM-IV have improved the reliability of diagnosing BD, replacing older terms like manic depression.

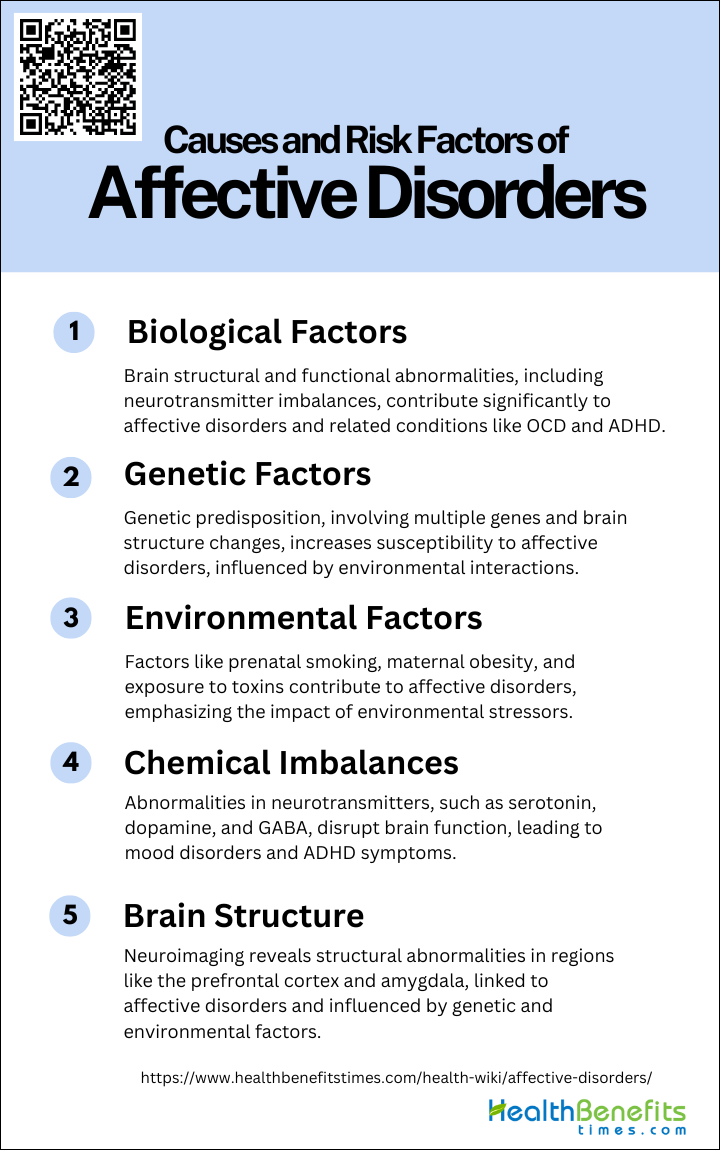

Causes and Risk Factors of Affective Disorders

Understanding the etiology of these conditions is crucial for prevention and treatment. Below is a list of recognized causes and risk factors that contribute to the development of affective disorders.

1. Biological Factors

Biological factors play a significant role in the development of affective disorders. Neuroimaging studies have shown that structural and functional abnormalities in the brain are associated with these disorders. For instance, deficits in cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical circuits have been observed in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), indicating that changes in white matter may contribute to the condition. Additionally, abnormalities in monoamine neurotransmitters, brain-derived neurotrophic factors, and imbalances in glutamic acid/γ-aminobutyric acid have been implicated in the pathogenesis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which shares some symptomatic overlap with affective disorders.

2. Genetic Factors

Genetic factors are crucial in understanding the susceptibility to affective disorders. Research indicates that these disorders likely result from multiple genes that confer a liability to develop the condition when combined with environmental risk factors. Studies on monozygotic twins have shown that genetic risk factors can lead to specific changes in brain structures, such as a decrease in inferior frontal white matter, which is associated with obsessive-compulsive symptomatology. Furthermore, mutations in specific genes, such as Latrophilin 3 (LPHN3), have been linked to increased susceptibility to ADHD, suggesting a genetic predisposition to affective disorders as well.

3. Environmental Factors

Environmental factors significantly influence the development of affective disorders. Prenatal smoking, maternal obesity, vitamin D and mineral deficiencies, and exposure to pesticides and lead have been identified as risk factors for ADHD, which can also contribute to affective disorders. Additionally, environmental stressors can exacerbate the symptoms of these disorders. For example, in monozygotic twins, environmental risk factors were associated with an increase in dorsolateral-prefrontal white matter, highlighting the impact of the environment on brain structure and function. These findings underscore the importance of considering environmental influences in the etiology of affective disorders.

4. Chemical Imbalances

Chemical imbalances in the brain are a well-documented cause of affective disorders. Abnormalities in monoamine neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, are commonly associated with conditions like depression and anxiety. These imbalances can disrupt normal brain function and lead to mood dysregulation. Additionally, the imbalance between glutamic acid and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has been implicated in the development of ADHD, suggesting that similar mechanisms may be at play in affective disorders. Addressing these chemical imbalances through pharmacological interventions is a common therapeutic approach for managing affective disorders.

5. Brain Structure

Structural abnormalities in the brain are linked to the development of affective disorders. Neuroimaging studies have revealed that various brain regions, including the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, and amygdala, show structural and functional changes in individuals with these disorders. For example, reduced gray matter volume has been associated with ADHD, which may also be relevant to affective disorders. In OCD, different white matter regions are affected by genetic and environmental risk factors, illustrating the complex interplay between these factors in altering brain structure. Understanding these structural changes is crucial for developing targeted interventions for affective disorders.

Sign and Symptoms of Affective Disorders

Recognizing the signs and symptoms is crucial for seeking timely intervention and support. The following list details these key indicators.

- Ongoing sad, anxious, or “empty” mood

- Feeling hopeless or helpless

- Having low self-esteem

- Feeling inadequate or worthless

- Excessive guilt

- Repeating thoughts of death or suicide, wishing to die, or attempting suicide

- Loss of interest in usual activities or activities that were once enjoyed, including sex

- Relationship problems

- Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much

- Changes in appetite and/or weight

- Decreased energy

- Trouble concentrating

- A decrease in the ability to make decisions

- Frequent physical complaints that don’t get better with treatment

- Running away or threats of running away from home

- Very sensitive to failure or rejection

- Irritability, hostility, or aggression

Treatment and Management for Affective Disorders

Tailoring strategies to individual needs is crucial for providing effective care. Below is a list of interventions commonly used to address these complex conditions.

1. Pharmacological Treatments

Pharmacological treatments for affective disorders primarily involve the use of antidepressants and mood stabilizers. Antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), are commonly used to treat major depressive disorder and anxiety symptoms. For bipolar disorder, mood stabilizers like lithium and anticonvulsants are often prescribed. Recent advancements have introduced newer classes of medications that target different neurotransmitter systems, offering better tolerability and safety profiles compared to older drugs. However, the management of these medications requires careful monitoring to avoid side effects and ensure therapeutic efficacy.

2. Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy is a prevalent treatment for affective disorders, either alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) have shown significant efficacy in treating acute affective and panic disorders. Well-being therapy, a novel approach based on Ryff’s conceptual model, has also demonstrated effectiveness in reducing residual symptoms and preventing relapse in remitted patients. Psychodynamic and supportive therapies are other psychotherapeutic approaches that aim to address both symptom relief and underlying personality issues. These therapies focus on the patient’s current problems and symptoms rather than character pathology or developmental psychodynamics.

3. Lifestyle Modifications and Complementary Therapies

Lifestyle modifications and complementary therapies play a crucial role in the management of affective disorders. Regular physical activity, a balanced diet, and adequate sleep are essential components of a healthy lifestyle that can significantly impact mood and overall well-being. Complementary therapies such as mindfulness meditation, yoga, and acupuncture have also been explored for their potential benefits in alleviating symptoms of depression and anxiety. These non-pharmacological interventions can be particularly useful in conjunction with traditional treatments, offering a holistic approach to managing affective disorders.

4. Specialist Procedures

Specialist procedures, including electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), are often considered for treatment-resistant cases of affective disorders. ECT is highly effective for severe depression and bipolar disorder, particularly when rapid symptom relief is needed. TMS, a newer non-invasive procedure, has shown promise in treating depression by stimulating specific brain regions. These procedures are typically reserved for patients who do not respond to conventional treatments and require specialized settings for administration. Ongoing research continues to explore the neurobiological mechanisms underlying these treatments to improve their efficacy and safety.