Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a group of inherited disorders characterized by impaired cortisol synthesis in the adrenal glands. It results from a deficiency of one of the enzymes required for cortisol production, with 21-hydroxylase deficiency being the most common form, accounting for about 95% of cases. The lack of cortisol leads to excessive production of androgens (male hormones), which can cause virilization (masculinization) in females, such as ambiguous genitalia at birth, early puberty, and excessive hair growth. In males, it can cause early puberty, accelerated growth, and small testes. Untreated classic CAH can lead to life-threatening adrenal crises due to cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is a group of inherited disorders characterized by impaired cortisol synthesis in the adrenal glands. It results from a deficiency of one of the enzymes required for cortisol production, with 21-hydroxylase deficiency being the most common form, accounting for about 95% of cases. The lack of cortisol leads to excessive production of androgens (male hormones), which can cause virilization (masculinization) in females, such as ambiguous genitalia at birth, early puberty, and excessive hair growth. In males, it can cause early puberty, accelerated growth, and small testes. Untreated classic CAH can lead to life-threatening adrenal crises due to cortisol and aldosterone deficiencies.

Causes of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

CAH is mainly caused by genetic mutations that result in enzyme deficiencies needed for cortisol production. The most common form, which accounts for more than 90% of cases, is caused by a deficiency in 21-hydroxylase due to mutations in the CYP21A2 gene. This deficiency hinders the conversion of 17-hydroxyprogesterone to 11-deoxycortisol, leading to a lack of cortisol and an excess of androgen precursors. This can cause symptoms like virilization in females and potential salt-wasting crises due to insufficient aldosterone synthesis. There are also other less common enzymatic defects that contribute to different clinical phenotypes depending on the specific enzyme affected, such as deficiencies in 11β-hydroxylase, 17α-hydroxylase, and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase. In some cases, mutations in the P450 oxidoreductase POR gene can result in a combined deficiency of CYP17A1 and CYP21A2, which presents with unique features like skeletal malformations and severe genital ambiguity. Understanding the genetic and enzymatic aspects of CAH is crucial for accurate diagnosis, management, and potential prenatal interventions.

Types of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

In CAH, the adrenal glands cannot make enough of these vital hormones due to genetic defects. There are several types of CAH, each with its own set of symptoms and underlying causes:

1. Classical CAH

This deficiency leads to cortisol deficiency, with or without aldosterone deficiency, and an excess of androgens. The severe classic form occurs in approximately one in 15,000 births worldwide and is often detected through neonatal screening. Patients with classical CAH may experience abnormalities in the adrenal medulla and epinephrine deficiency. Genetic alterations in the C4/21-OH gene region are typically responsible for this form, often linked to the HLA-Bw47 antigen. Standard hormone replacement therapy is used for management, although it often fails to achieve normal growth and development, leading to complications such as iatrogenic Cushing’s syndrome, hyperandrogenism, infertility, and metabolic syndrome in adulthood.

2. Non-classical CAH

Non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NC-CAH) is a milder form of CAH, also caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency, but with less severe genetic mutations compared to the classical form. The prevalence of NC-CAH ranges from 0.6% to 9% in women with androgen excess. Clinical manifestations of NC-CAH are highly variable, including asymptomatic cases, premature pubarche, hirsutism, acne, menstrual irregularities, infertility, and increased rates of spontaneous abortions. Diagnosis is typically based on elevated basal and/or ACTH-stimulated 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels. Metabolic consequences, such as increased cardiovascular risk factors, obesity, and insulin resistance, are observed in NC-CAH patients, potentially leading to cardiometabolic diseases in adulthood. Unlike classical CAH, growth disorders and decreased bone mineral density are not consistently observed in NC-CAH patients. Glucocorticoid therapy is tailored to clinical symptoms, and during pregnancy, steroid replacement and monitoring is crucial to reduce the risk of spontaneous abortions.

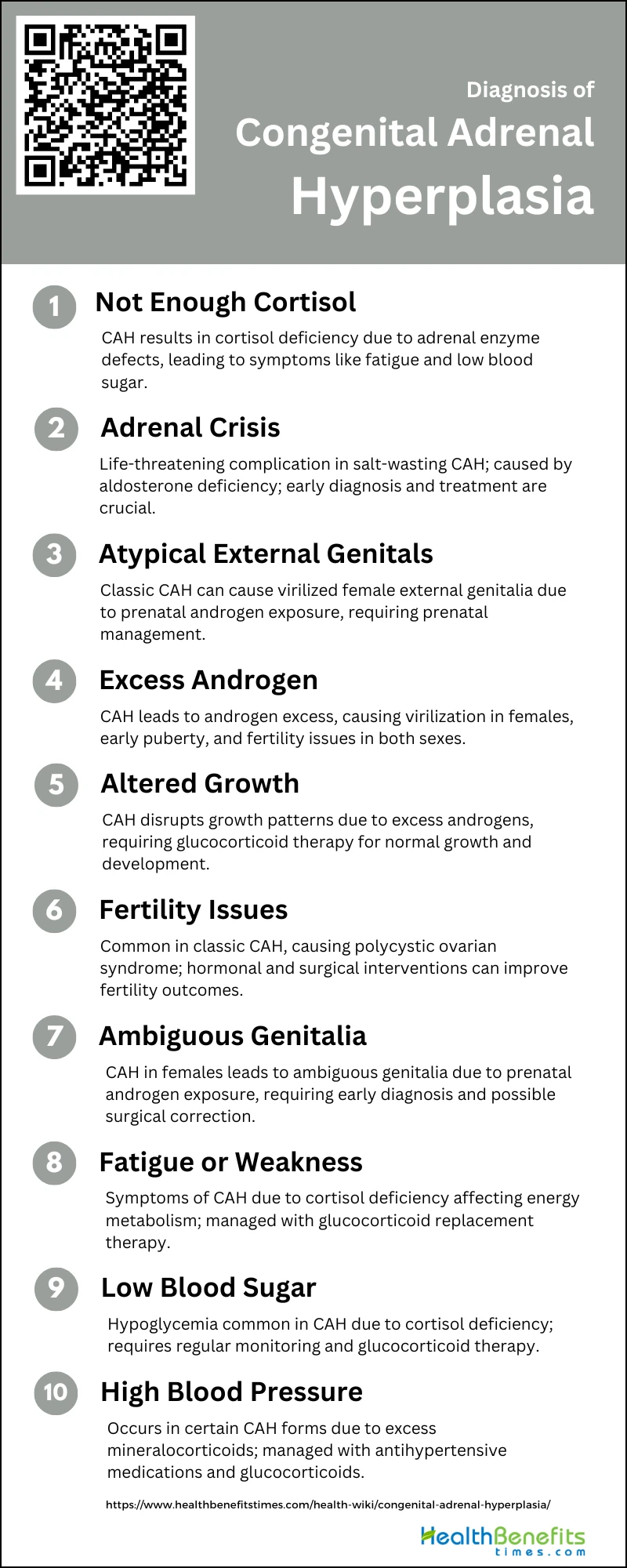

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Symptoms can range from mild to severe and are often present from birth or early childhood. Accurate diagnosis typically involves a combination of clinical evaluation, blood tests, and genetic screening.

1. Not Enough Cortisol

CAH is primarily characterized by a deficiency in cortisol production due to enzymatic defects in the adrenal cortex, most commonly 21-hydroxylase deficiency. This deficiency disrupts the normal feedback mechanism to the pituitary gland, leading to an overproduction of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and subsequent adrenal hyperplasia. The lack of cortisol can result in symptoms such as fatigue, weakness, and low blood sugar levels.

2. Adrenal Crisis

Adrenal crisis is a potentially life-threatening condition associated with CAH, particularly in the salt-wasting form of the disease. This occurs due to the inability to produce sufficient aldosterone, leading to severe dehydration, low blood pressure, and electrolyte imbalances. Early diagnosis and treatment with glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid replacement are crucial to prevent adrenal crises and reduce mortality.

3. External Genitals That Don’t Look Typical

Females with CAH, especially those with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency, are often born with virilized external genitalia due to prenatal exposure to excess androgens. This can result in ambiguous genitalia, making it difficult to determine the sex of the newborn at birth. Prenatal treatment with dexamethasone has been shown to reduce or prevent virilization in affected female fetuses.

4. Too Much Androgen

Excess androgen production is a hallmark of CAH, leading to various symptoms depending on the severity and timing of the androgen exposure. In females, this can cause virilization of the external genitalia, while in both sexes, it can lead to early onset of puberty and rapid growth. Androgen excess can also result in fertility issues and polycystic ovarian syndrome in females.

5. Altered Growth

Children with CAH often experience altered growth patterns due to excess androgen production. This can result in accelerated growth and early closure of growth plates, leading to shorter adult stature if not properly managed. Glucocorticoid therapy is essential to control androgen levels and ensure normal growth and development.

6. Fertility Issues

Fertility issues are common in individuals with CAH, particularly in females with classic 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Excess androgen production can lead to polycystic ovarian syndrome and other reproductive abnormalities. Proper hormonal management and surgical interventions can help improve fertility outcomes in affected individuals.

7. Ambiguous Genitalia in Female Newborns

Ambiguous genitalia is a significant diagnostic feature of CAH in female newborns. This condition arises from prenatal androgen exposure, leading to varying degrees of virilization. Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment, including possible surgical correction, are crucial to address the physical and psychological impacts of ambiguous genitalia.

8. Fatigue or Weakness

Fatigue and weakness are common symptoms in individuals with CAH due to cortisol deficiency. Cortisol is essential for energy metabolism and stress response, and its deficiency can lead to chronic fatigue and muscle weakness. Glucocorticoid replacement therapy is necessary to manage these symptoms and improve quality of life.

9. Low Blood Sugar

Low blood sugar, or hypoglycemia, is a frequent complication in CAH patients due to insufficient cortisol production. Cortisol plays a critical role in glucose metabolism, and its deficiency can result in recurrent episodes of hypoglycemia, particularly during periods of stress or illness. Regular monitoring and appropriate glucocorticoid therapy are essential to prevent hypoglycemic episodes.

10. High Blood Pressure

High blood pressure can occur in certain forms of CAH, such as 11β-hydroxylase deficiency, due to excess production of deoxycorticosterone, a mineralocorticoid with hypertensive effects5. Proper diagnosis and management, including the use of antihypertensive medications and glucocorticoid therapy, are necessary to control blood pressure and prevent long-term cardiovascular complications.

Complications of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Complications of CAH are multifaceted and can significantly impact patients’ quality of life. Infertility is a notable issue, with both men and women experiencing reduced fertility due to various factors such as elevated adrenal androgens and, in women, high serum progesterone levels that hinder ovulation and embryo implantation. Additionally, patients with the salt-wasting form of CAH face more severe complications, including increased virilization and difficulties in establishing heterosexual relationships and conceiving children. Neurological complications, although rare, can occur, as evidenced by a case where a patient developed severe brain damage following episodes of hypernatremia and hypoglycemia. Long-term outcomes for CAH patients often include increased mortality, morbidity, and risks for metabolic disorders, partly due to the adverse effects of glucocorticoid therapy. Despite these challenges, advancements in management and prenatal treatments are being developed to improve patient outcomes. Below is a list of common complications associated with this condition.

- Diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Dehydration

- Confusion

- Low blood sugar levels

- Seizures

- Shock

- Coma

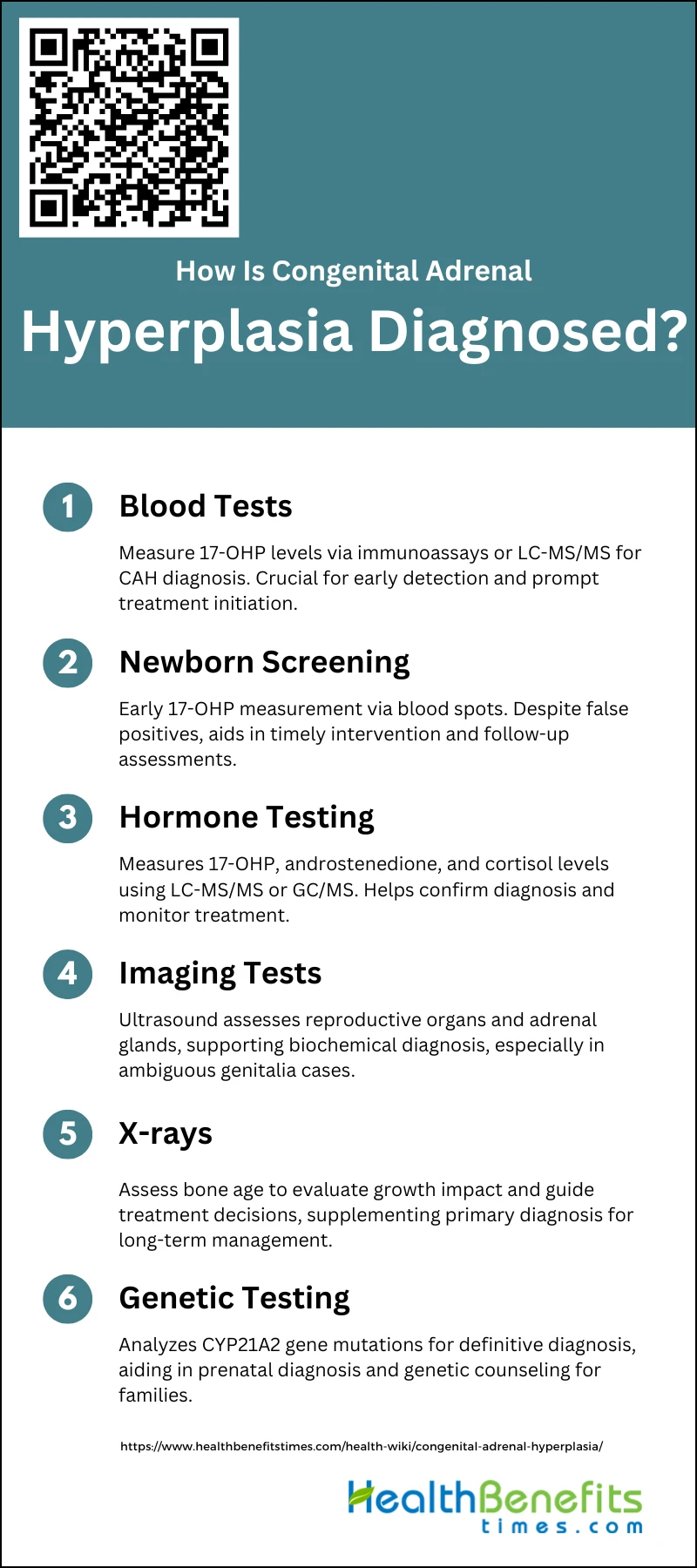

How Is Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia Diagnosed?

Early diagnosis is crucial for proper treatment and management of this condition. The diagnostic process typically involves the following steps:

1. Blood Tests

Blood tests are a fundamental method for diagnosing Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia (CAH). These tests typically measure levels of 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP), which is elevated in individuals with CAH due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Various techniques such as immunoassays, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), and radioimmunoassays are employed to measure 17-OHP levels in blood samples. LC-MS/MS, in particular, has shown improved specificity and reduced false-positive rates compared to traditional immunoassays. Blood tests are crucial for early diagnosis, enabling timely treatment to prevent severe complications such as salt-wasting crises and dehydration.

2. Newborn Screening

Newborn screening for CAH is a routine practice in many countries and involves measuring 17-OHP levels in blood spots collected on filter paper, typically between 2 and 4 days after birth. This early screening is vital for identifying affected infants before they develop severe symptoms. Various assay techniques, including radio-immunoassay, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and time-resolved fluoro-immunoassay, are used for initial screening. Despite the high false-positive rates associated with these methods, second-tier tests like LC-MS/MS can significantly improve the positive predictive value, reducing unnecessary follow-up evaluations.

3. Hormone Testing

Hormone testing is essential for diagnosing CAH and involves measuring various steroid hormones such as 17-OHP, androstenedione, and cortisol. These tests help confirm the diagnosis and differentiate between different types of CAH. Advanced techniques like LC-MS/MS and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) are used to measure these hormones accurately. These methods can simultaneously quantify multiple steroids, providing a comprehensive hormonal profile that aids in diagnosis and management. Hormone testing is particularly useful in cases where initial screening results are ambiguous or when monitoring treatment efficacy.

4. Imaging Tests (such as an Ultrasound Study)

Imaging tests, including ultrasound studies, play a supportive role in diagnosing CAH, especially in cases with ambiguous genitalia. Ultrasound can help assess the internal reproductive organs and adrenal glands, providing additional information that supports the biochemical diagnosis. For instance, ultrasound can identify adrenal hyperplasia or other structural abnormalities that may be associated with CAH. While imaging is not the primary diagnostic tool, it is valuable in comprehensive evaluations, particularly in prenatal settings where it can help in early identification and management of affected fetuses.

5. X-rays

X-rays are occasionally used in the diagnosis of CAH to assess bone age, which can be advanced in children with untreated CAH due to excess androgen production. Bone age assessment helps in evaluating the impact of the disease on growth and development, guiding treatment decisions. Although not a primary diagnostic tool, X-rays provide supplementary information that can be crucial for long-term management and monitoring of children with CAH. This imaging modality is particularly useful in cases where growth abnormalities are suspected, helping to tailor appropriate therapeutic interventions.

5. Genetic Testing

Genetic testing is a definitive method for diagnosing CAH, particularly in cases where biochemical tests are inconclusive. It involves analyzing the CYP21A2 gene, which is responsible for 21-hydroxylase deficiency, the most common cause of CAH. Genetic testing can identify specific mutations, aiding in accurate diagnosis and enabling prenatal diagnosis and genetic counseling for families with a history of CAH. Noninvasive prenatal testing using cell-free fetal DNA in maternal plasma has also been developed, allowing for early diagnosis and timely intervention to prevent complications. Genetic testing is invaluable for confirming the diagnosis and planning long-term management strategies.

Treatment and Management for Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia

Proper treatment and management are crucial for individuals with CAH to maintain optimal health and prevent complications. Below include a key of interventions and management strategies for those living with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia:

1. Steroid Replacement Therapy

Steroid replacement therapy is the cornerstone of managing congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), particularly due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency. The primary goal is to replace deficient cortisol with suitable glucocorticoids (GC) and aldosterone with mineralocorticoids (MC) to prevent adrenal crises and virilization, allowing normal growth and development. Hydrocortisone is the most frequently used glucocorticoid, with doses adjusted based on age and clinical response. Continuous subcutaneous hydrocortisone infusion (CSHI) has shown promise in approximating physiological cortisol secretion, improving adrenal steroid control, and enhancing quality of life. Despite these advancements, challenges remain in balancing under- and overtreatment to avoid long-term complications such as obesity, osteoporosis, and reduced fertility.

2. Surgery

Surgical intervention, specifically bilateral laparoscopic adrenalectomy, is considered for patients with classic CAH who have poor hormonal control despite optimal medical therapy. This procedure has been shown to reduce the need for high doses of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, improve symptoms of hyperandrogenism, and restore regular menstruation in females. Adrenalectomy may be superior to conventional medical therapy in selected patients, particularly those with severe hirsutism, acne, and amenorrhea. However, it is crucial to monitor for potential complications such as adrenal rests, which may necessitate adjustments in replacement therapy. The decision for surgery should be made by a multidisciplinary team, considering the patient’s overall health, hormonal control, and quality of life.